According to information from historical chronics, during the time of reign of Emperor Monmu (文武天皇, 681-707), the entire Japan territory was divided for the seven administrative divisions located across the seven main roads. This system was adopted from China and there was called goki-shichidō (五畿七道) with Chinese-style dō pronunciation instead of traditional Japanese michi. The region Kibi (吉備) was placed on the San ́yōdō (山陽道) road and in turn consisted of three province: Bizen (備前), Bitchū (備中), and Bingo (備後). Traditionally, the provinces along San ́yōdō were among the richest. This three provinces of the Kibi region shared a border, and the three rivers Yoshii, Asahi and Takabashi run down from the mountains in this area, depositing high grade iron sand (satetsu, 砂鉄) on their banks. Going east to west, distributed on these rivers in the Kamakura period would be the Ko-Yoshi and Ko-Osafune schools (on the Yoshii), the Ko-Ichimonji, Fukuoka Ichimonji and Yoshioka-Ichimonji (on the Asahi), and the Kamakura Ichimonji and Ko-Ichimonji schools on the Takahashi.

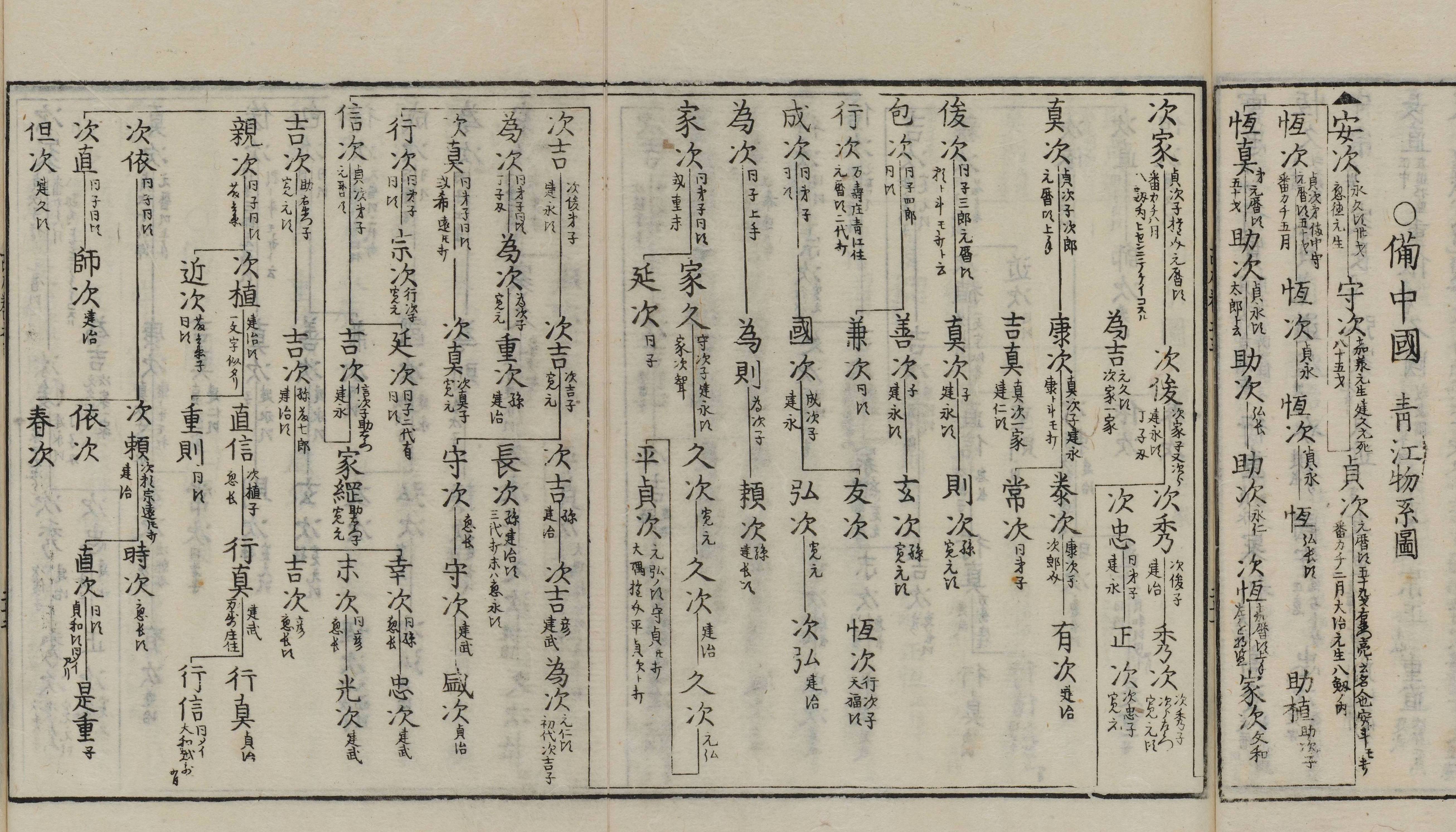

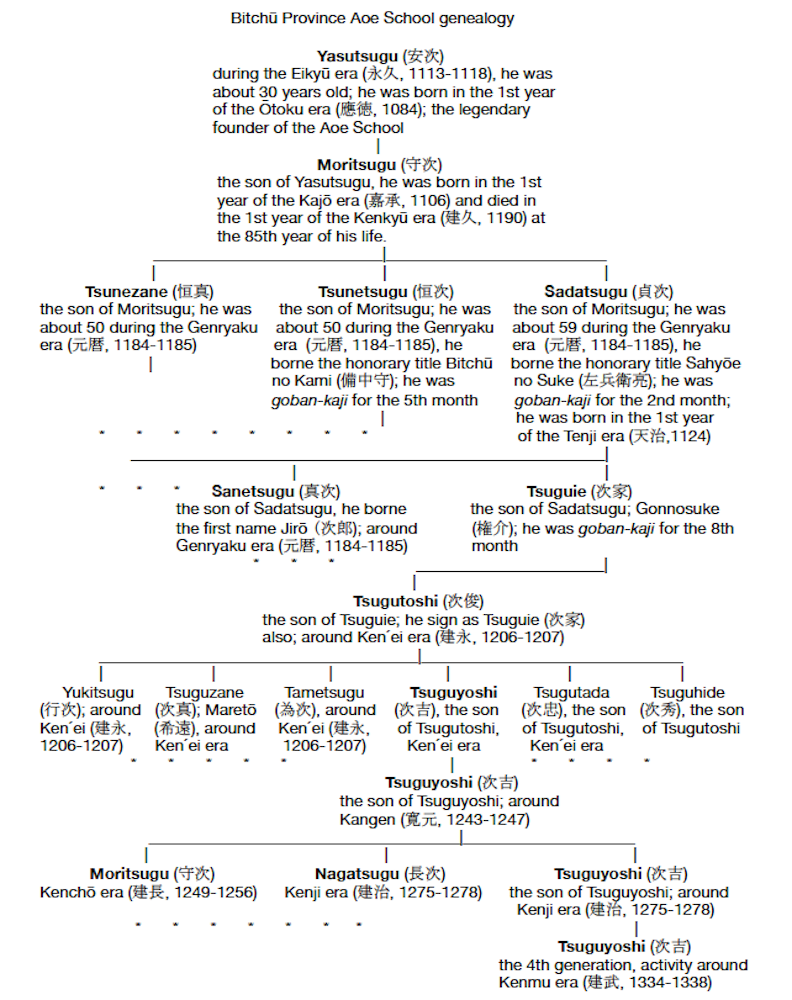

The Aoe (青江) smiths are said to take their name from a subdivision of the Fukuyama (福山) village, in Mizu of Bingo province. From here they transplanted to Bitchū province but preserved the name of their origin. The Aoe name is still seen in this area today, between the Asahi and Takahashi rivers. Yasutsugu (安次) is said to be the founder of the Aoe from around 1120 AD, but his work isn’t seen anymore.

Now the actual distances involved here are quite small. Travelling 35 kilometers in a straight line you would cross over this entire territory of these three rivers from Osafune to Aoe and all the smiths in between. This small area was the major pulsing factory that over 500 years produced so many great works that they account for approximately 40% of all the existing Jūyō Tōken today. The difference between Bizen origin and Bitchū origin is basically which side of the Asahi river you live on, and leads us to understand more clearly the close relationship between these smiths and schools. Though they are a stone’s throw away, the difference is locality did produce some marked difference in workmanship.

The convention of the Hon'ami was to maintain five traditions during the Kotō period: Yamashiro, Sōshū, Yamato, Bizen and Mino. The reality of this is that it is a simplification meant to try to subdivide an unwieldy number of regional traditions based on local materials and techniques. For example, the Kyūshū smiths which predate Samonji are not easily classified. We tend to throw them in with Yamato because the workmanship is a bit antique and unsophisticated seeming but this is not a fair distinction. Kyūshū style is Kyūshū style, but that does not really assist us in trying to take a bird's eye view and discuss nihontō in non-specific terms. So in this classification system some lines are blurred and schools can be related by reason of being more alike than dissimilar while other schools may share bloodlines so will be classified in the same tradition. Bizen and Bitchū styles, the latter of which contains Aoe, have intermingled and though they are distinct, Aoe is associated with Ichimonji, Osafune, etc. under this one big tent of “Bizen Tradition” works. As a result, for western collectors, it can pass by somewhat in stealth mode under the shadow of the name of its neighboring province. Dr. Honma however sorts them out as standing at a peer level with Bizen, Yamato, and Yamashiro in the Kamakura and earlier times rather than under the umbrella of Bizen.

Aoe as a style is often thought to bridge a gap between the chōji developments of Bizen and the suguba and refined jigane styles of Awataguchi and Rai in Yamashiro. Ko-Aoe works are also considered to be among the most elegant blades, with deep koshizori and ko-kissaki that connect them strongly to the early years of tachi making, while the Chū-Aoe works brought the art of steel to its highest level in Bitchū.

Figure 1. Bitchū Province Aoe School genealogy. The Kotō Meizukushi Taizen (古刀銘盡大全), Volume 3, pp. 41/2, 42/1, 42/2.

Competing nomenclature: Ko-Aoe, Chū-Aoe or Sue-Aoe.

The smiths of the Ko-Aoe (古青江) group gave way to those we just call Aoe at the end of the Kamakura period. There are different sets of names used by different authors and schools of thought. The first divides Aoe into Ko-Aoe (old Aoe) up until the Kamakura period, then calls these smiths Chū-Aoe (中青江,middle Aoe) up until the Nanbokucho period, then calls the last group Sue-Aoe (末青江, end Aoe) until they extinguish some time in the Muromachi period.

The second set of nomenclature only uses Ko-Aoe and includes in this group smiths working up until the late Kamakura period, then uses Chū-Aoe to cover the smiths working until Aoe fades away. Sometimes Sue-Aoe is used for specific Muromachi period finds in this case. The third set of nomenclature would be to just use Ko-Aoe, and Aoe for the rest. In this case the NBTHK would attribute a blade to Aoe school, and in this imply that it is a blade from the Kamakura-Nanbokuchō border period up until the Muromachi period. If they mean older they will specifically call it Ko-Aoe then, which will place it into the Kamakura period. We like to think of these period divisions as very sharp borders but it's not the case. Everyone did not suddenly wake up one day and say well, it's 1334, we all need to change our styles. So in this case Aoe can also be thought of to be a bit of a broader umbrella which will cover some time going into the end decades of the Kamakura period where the styles were beginning to evolve into the Nanbokuchō style.

This is important to recognize because any particular smith may at times be referred to as Aoe, Sue-Aoe or Chū-Aoe depending on which system the author is using, but they will all be saying the same thing.

During the Nanbokuchō period the smiths of Aoe seem to have maintained traditions while Bizen went off into experiments and began producing nioi-deki swords. Aoe maintained development in nie but we see Bizen features in their blades still, usually with utsuri but also we see several special features that are unique to this school that causes it to be distinct from the rest of the Bizen schools and exposes some of the line blurring required for the Hon’ami five schools concept to be deployed. They furthermore preserved the chōji hamon in the form of saka-chōji (逆丁子, slanting chōji) when all of the other Bizen schools saw it fade away and they resisted the Sōshū influence which took over in Osafune after the Ichimonji schools fell into obscurity.

These features are those that were specific or best made by the smiths of Aoe:

- chirimen-hada (縮緬肌) a crinkled texture that reminds one of crepe silk. This hada is formed by embedding fine patterned itame within mokume patterns during forging and then coating it all with ji-nie (Tanobe sensei points out however that the true secret to doing this has been lost).

- sumi-hada (澄肌) areas where the steel color changes, said to be “dark but clear”. Dr. Honma says that this is a softer type of steel and is one of the key things to look for in Aoe kantei.

- dan-utsuri (段映り) multiple layers of interesting ghostly patterns in the ji. The term utsuri means a reflection, and usually it is some kind of reflection in the hamon. The exact structure of utsuri is still open for debate, and not all utsuri is a simple reflection of the hamon but as we see in Aoe works it can be multi-layered and complex and exceedingly beautiful, making the works of this school very special when the utsuri is very good. The earliest utsuri began with areas called jifu which look like fingerprints, and then would extend to become midare or chōji-utsuri which appear to mirror the hamon (hence the name coming from the word for reflection). The smiths of Aoe were able to layer several different patterns of jifu and midare on top of each other to produce a three dimensional effect. This is overlaid with suji-utsuri which is one to three levels of horizontal utsuri which parallels the cutting edge the way the sky glows when the sun is setting. When you rotate such a blade through the light you will see many different effects in the ji as a result of all of this subtle utsuri work. The Aoe smiths may have had access to a particular grade of iron sand in their locale that other schools did not. This exposed special properties when worked and from its basic discovery the Aoe smiths worked on enhancing and developing utsuri in their work.

- namazu-hada (鯰肌) it is not seen so much but is meant to describe areas of dark hada which appear to have no texture and this reminded the old sword judges of catfish skin that had no scales, from where it takes its name. There would be texture here but this still would have been forged so tightly that it became muji and then was mixed in with steel with less forging and embedded into it. One can theorize that this was ongoing experiments with making hybrid materials that better stood up to the wear and tear of everyday use.

- katana-mei (刀銘) the Aoe smiths in the older periods tended to sign in two characters, and the kanji Tsugu (次) is commonly handed down through their lines going for centuries. During the Nanbokucho period many Aoe smiths began to sign on the opposite side of the blade to everyone else in Japan... this began earlier in the Heian period (平安, 794-1185) with one of the Yasutsugu group smiths and several other Aoe smiths signed on either side. What this means is now a subject for speculation only, but the best reason is given by one of Satō Kanzan's students in the Tōken Bijutsu.

About the reasons for katana mei, we don't know for sure as no records were handed down. The Tōken Bijutsu relates a theory:

[...] since the [signature] was to represent the maker's spirit and conscience as well as forpreventing forgery, the act of inscribing in a non-conformist way had a meaning in itself.

— Tōken Bijutsu

That is to say, it was a way of saying we are different, and we are special, those of us making these swords in Aoe.

At the end of the Kamakura period we also see many examples of signature and date appearing on the same side, and this too is unusual to see (these are called kaki-kudashi-mei, 書下し銘). Signatures also changed from two character signatures to full length signatures featuring the name of the province, similar to what happened in Bizen nearby (and also in Yamato as some of the rare Yamato signatures do list the province in them). For some reason this did not seem to spread to Yamashiro, though it is certainly seen in Sōshū too.

As we proceed through the Nanbokucho period, the Aoe techniques split, where the traditional style based on suguba was continued and also a style based on Bizen chōji-midare but with slanted midareba was developed (and shared with the Katayama-Ichimonji smiths where it may have originated). Some of the works in the Nanbokuchō period became quite massive and as a result most lost their signatures in the Edo period when they were cut down in size to wear as katana. Because of the lack of signatures at this time due to shortening, many swords made by the Nanbokuchō Aoe smiths now only carry an attribution to the school. Confusion is made worse by the Aoe School consistently handing down names like “Moritsugu” and others through the years, and then having no date... making signatures appearing consistently though the era and work style changed. This makes it very hard to know which is which, just that through the workmanship's common denominators as described above they can be put to the same school and/or period.

While these changes were going on, the Aoe jihada also became more refined and beautiful with tight, jewel-like ko-itame becoming seen and the sori straightened out with large kissaki and massive shapes which is a common thread in Nanbokuchō schools. We see katana-mei very rarely in the Nanbokucho as this tradition was mostly dropped. Nie and ko-nie development was left behind in favour of nioi from neighbouring Bizen as well. Sumi-hada increased and chirimen-hada decreased. Though these works were highly skilled and easily at the level of the main line Bizen smiths working in Osafune, Aoe work at the top levels seems to have suddenly come to an end at the beginning of the Muromachi period (室町時代, 1336-1573). This would conclude the majority of a 400 year span of work that reached the top levels of artistry.

Aoe Tsuguyoshi (青江次吉)

Aoe Tsuguyoshi is the top smith of the middle period Aoe school. His work span is thought to be from the Kenmu era (建武, 1334-1338) to the Jōji era (貞治, 1362-1368). As mentioned above there are various nomenclature systems, so he may be referred to as Chū-Aoe or Sue-Aoe depending on the case but he is a smith who appears immediately after the Kamakura period and he seems to have captained the rise to prominence of the middle Aoe smiths. It s said that he borne the fist name Genjirō (源次郎) and honorary title Sakon Shōgen (左近将監).

The other excellent smiths oft he middle Aoe period are Moritsugu, Sadatsugu and Tsuguyoshi. Their work took similar forms, and one oft he main features we look for is saka-chōji (slanting chōji) which is something of a specialty. Even in the case of working in suguha, examination can reveal the saka-ashi (slanting ashi) that align with this style they specialized in. Many of the mumei Aoe school blades from the middle period have been made by these three masters and when the signature is lost they can be hard to surely attribute, judges for centuries have simply designated them as Aoe. Because their tachi were made with great lengths, many of them have lost their signatures and as such fall into these mumei groups. Only very rarely will a mumei blade be directly attributed to Tsuguyoshi. Tsuguyoshi great regard has him ranked by Fujishiro at jōjō-saku (上々作—a very high level of skill), as well the Edo period cutting masters ranked him at O-wazamono for superior cutting blades.

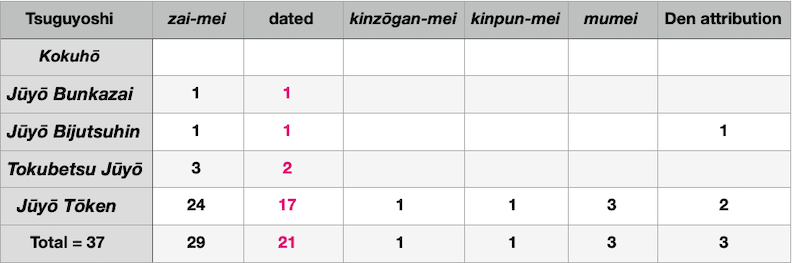

As of today, 37 swords are known (Jūyō and above) to be Tsuguyoshi’s work. Of all his works known to us, 1 sword (tachi) have Jūyō Bunkazai status; 3 swords are Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken; and 31 are Jūyō Tōken. Another 2 swords were awarded Jūyō Bijutsuhin status in their time.

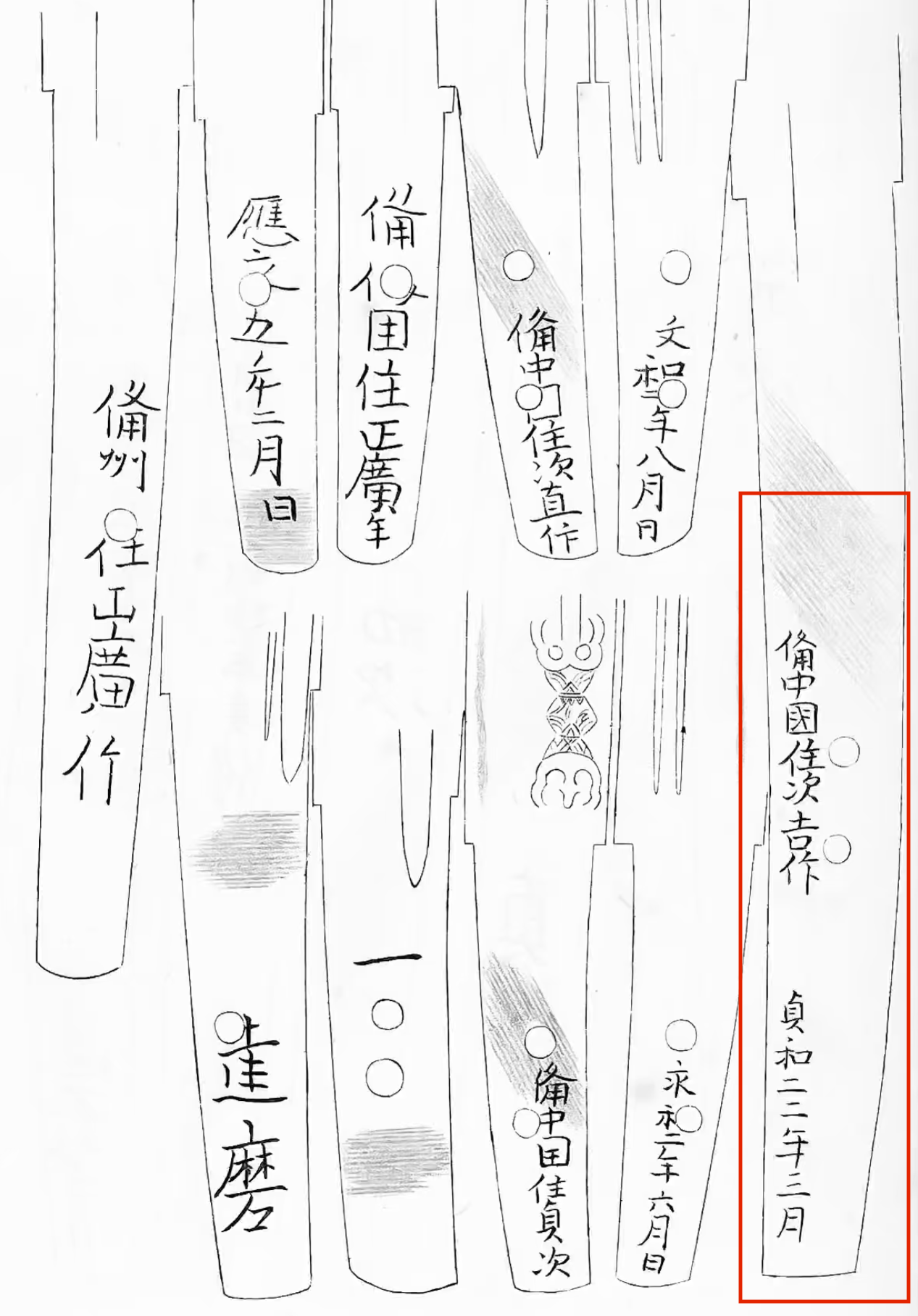

A very large percentage of dated swords is noteworthy: 72.4%. From this we can conclude that Tsuguyoshi very often signed and dated his works. In addition, there is another pattern in Tsuguyoshi's dating of his works. In the event that he put the date of production on tachi, then he put this date on the same side as the signature (haki-omote). That is, he often used the so-called kaki-kudashi-mei (書下し銘): signature where the entire inscription consisting of the smith’s name and the date are chiselled in one row and on one side of the tang. As of today are known 7 Jūyō tachi by Tsuguyoshi, signed in this manner. Thus, it is quite possible that dating of this tachi was lost after suriage process.

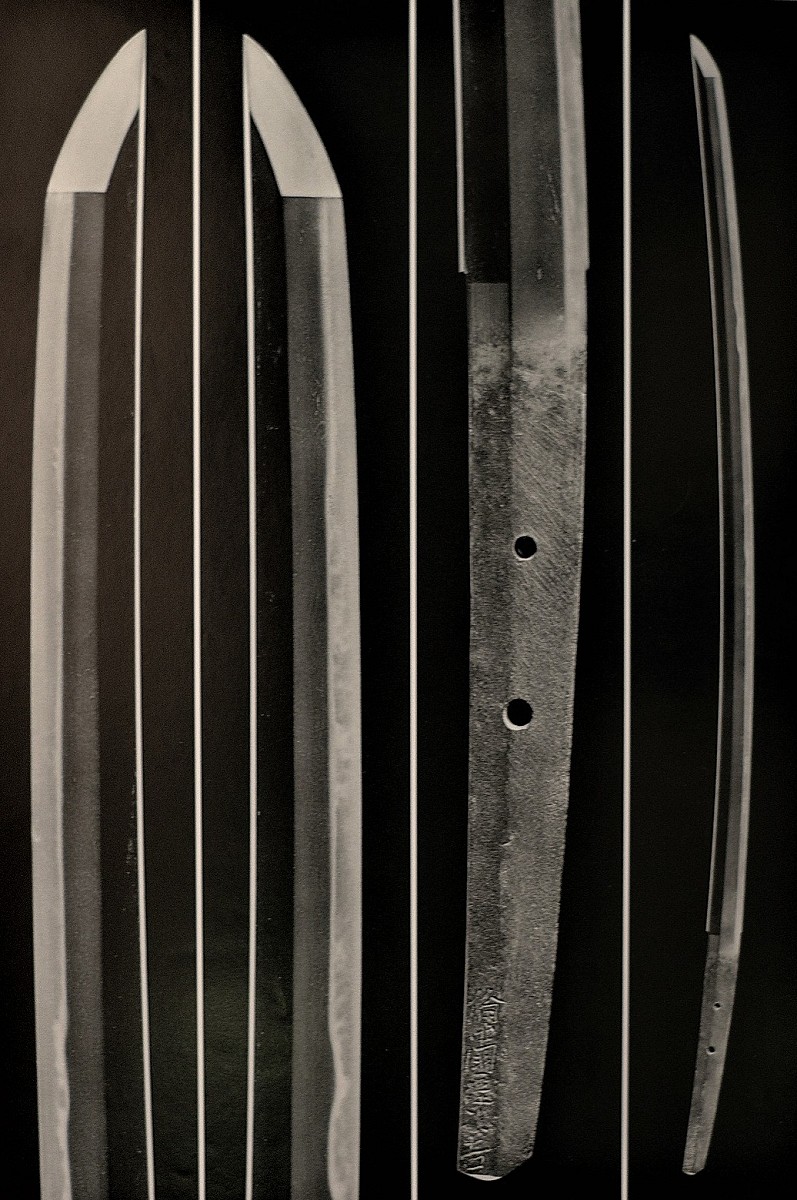

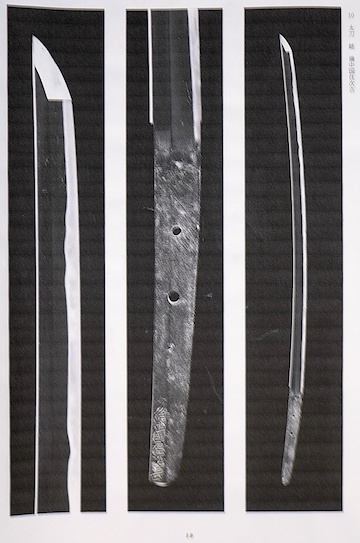

Figure 2. Tsuguyoshi's signature example. Kōzan Oshigata (光山押形), Volume 2, p. 28.

Author: Darcy Brockbank (published on www.yuhindo.com).

Edition and Supplements: Dmitry Pechalov.

This blade is really a special piece in all ways. It is a masterpiece of Tsuguyoshi and shows off the extremely high skill of the middle period Aoe smiths. The length and size demonstrate well what a great Nanbokuchō blade looked like. The preservation is beyond what one could hope for. It’s a rare katana mei, and signed Nanbokuchō tachi themselves are things that are very hard to find. Obviously, this one is highly recommended.

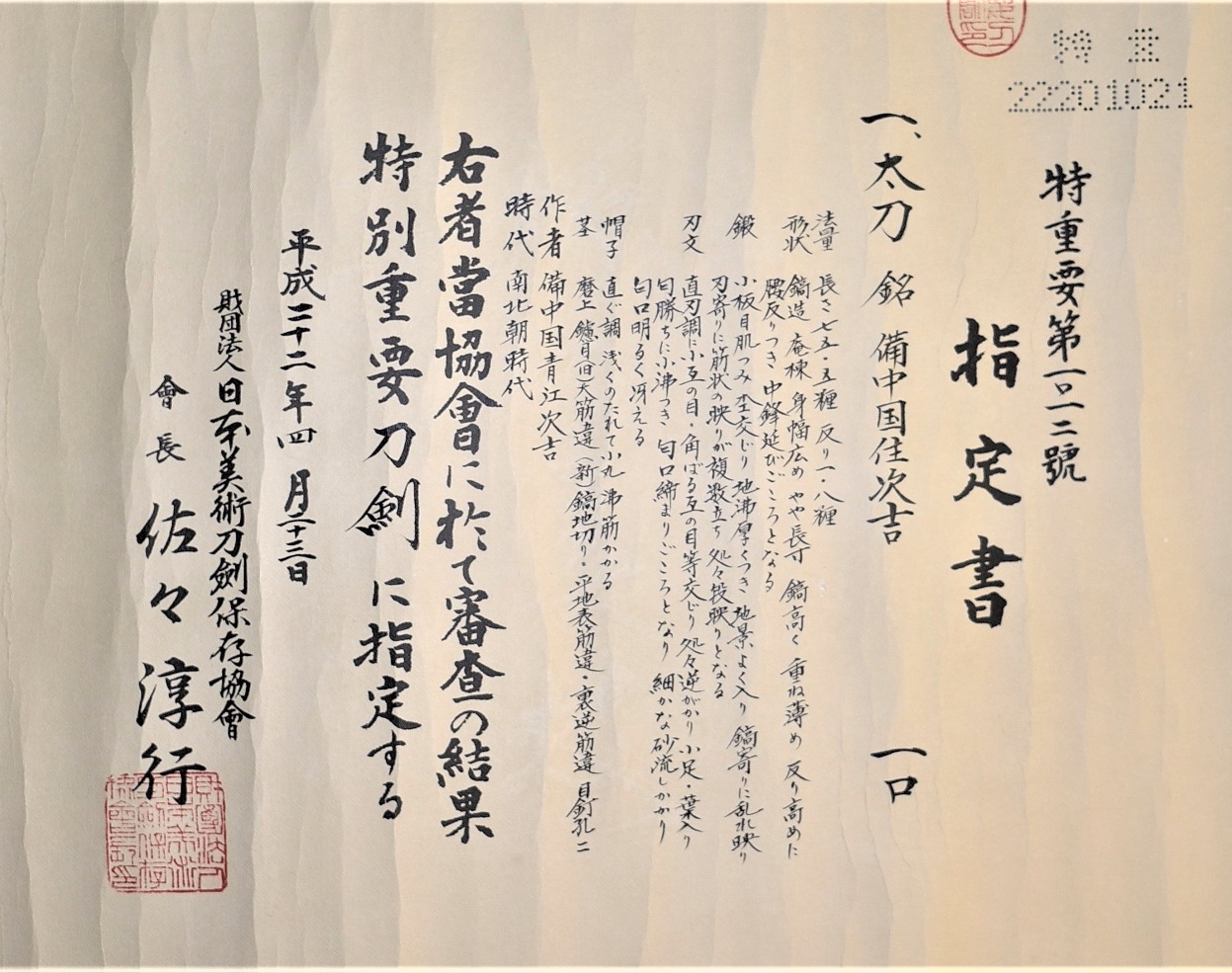

Tokubetsu Jūyō setsumei translation.

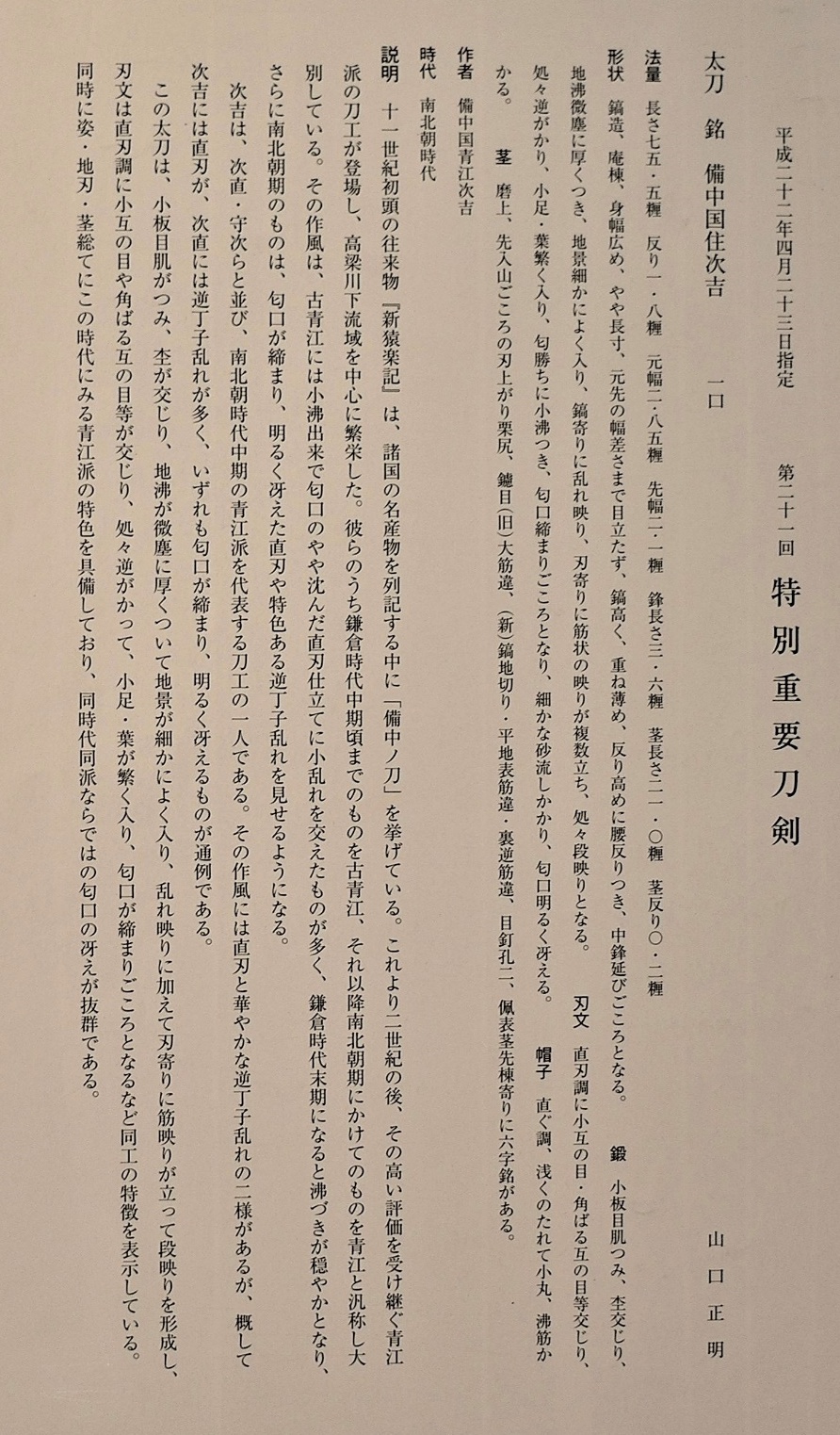

Designated as Tokubetsu Jūyō-tōken at the 21st tokubetsu jūyō-shinsa held on the 22th April, 2010.

TACHI: Signed by Bitchū (no) Kuni-jū TSUGUYOSHI (備中国住次吉)

Owner: Mr. Yamaguchi Masaaki (山口正明)

Measurements: nagasa – 75.50 cm; sori – 1.80 cm; motohaba – 2.85 cm; sakihaba – 2.19 cm; nakago sori – 0.20 cm; nakago nagasa – 21.0 cm; kissaki nagasa – 3.90 cm.

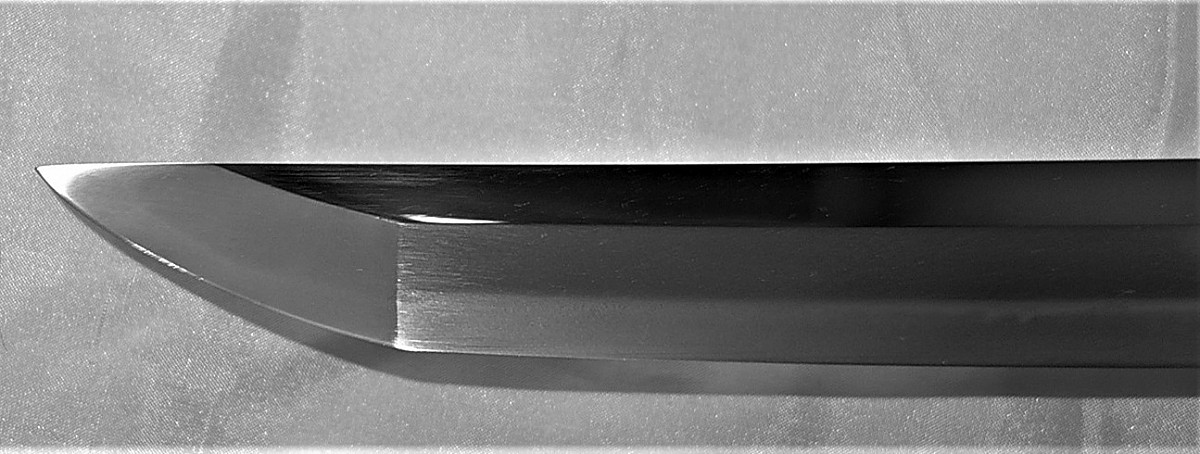

Sugata: the blade is in shinogi-zukuri with iori-mune wide mihaba, relatively long nagasa, no noticeable taper. High shinogi, thin kasane, deep koshizori, rather elongated chū-kissaki.

Kitae: dense ko-itame hada mixed with mokume, in addition plenty of ji-nie, lot of fine chikei, a midare-utsuri towards the shinogi and a linear utsuri towards the ha which combine to a dan-utsuri in places.

Hamon: suguha-chō mixed with ko-gunome, angular gunome, some slanting elements, ko-ashi connected with yō, and fine sunagashi, the hardening is in nioi-deki with ko-nie, the nioiguchi is rather tight, bright and clear.

Bōshi: sugu-chō with a little notare that runs back as ko-maru with some nie-sugi.

Nakago: suriage and ha-agari kurijiri which tends to become iriyamagata, the initial yasurime were ō-sugikai, the new yasurime are kiri on the shinogi-ji, sujikai on the hira-ji on the omote side, and gyaku-sujikai on the hira-ji on the ura side, there are two mekugi-ana and the haki-omote side bears at the tip oft he tang and towards the nakago-mune a six character signature.

Smith: Aoe TSUGUYOSHI from Bitchū province.

Period: Nanbokuchō period (1338).

Explanation: Swords from Bitchū are found in the early 11th century work of fiction

Shinsarugakuki (新猿楽記) that lists noted products of all provinces. The Aoe school that emerged later and flourished at the downstream of the Takahashi river continued to live from it fame. Generally, works made by this school up to the mid-Kamakura period are referred to as Ko-Aoe and those made later and throughout the Nanbokuchō period to just as Aoe. The workmanship of the Ko-Aoe school displays mostly a suguha-chō in ko-nie-deki with a rather subdued nioiguchi that is mixed with ko-midare.

From the late Kamakura period on, the nie become more unobtrusive and with the Nanbokuchō period, the school focussed on a saka-chōji-midare with a tight nioiguchi that is based on a bright and clear suguha. Tsuguyoshi, together with Tsugunao and Moritsugu was one of the best representative smiths of the Nanbokuchō period Aoe School who either worked in suguha or in a flamboyant saka-chōji-midare but generally it can be said that Tsuguyoshi focused more on a suguha whereas Tsugunao mostly hardened a saka-chōji-midare, in either case always with a tight, bright and clear nioiguchi.

This Tachi shows a dense ko-itame hada that is mixed with mokume and that features plenty of ji-nie, lot of fine chikei, a midare-utsuri, and in addition to that a linear utsuri which combine to a dan-utsuri in places. The hamon is a suguha-chō that is mixed with ko-gunome, angular gunome, some slanting elements in places, ko-ashi, and connected yō and features a rather tight nioiguchi whereas we can recognize the characteristic features of this smith. The blade is typical in terms of sugata, jiba, nakago and other elements for the Nanbokuchō period Aoe School and the clarity of the nioiguchi is outstanding among all works from that time. Thus we have a masterpiece work of Tsuguyoshi.

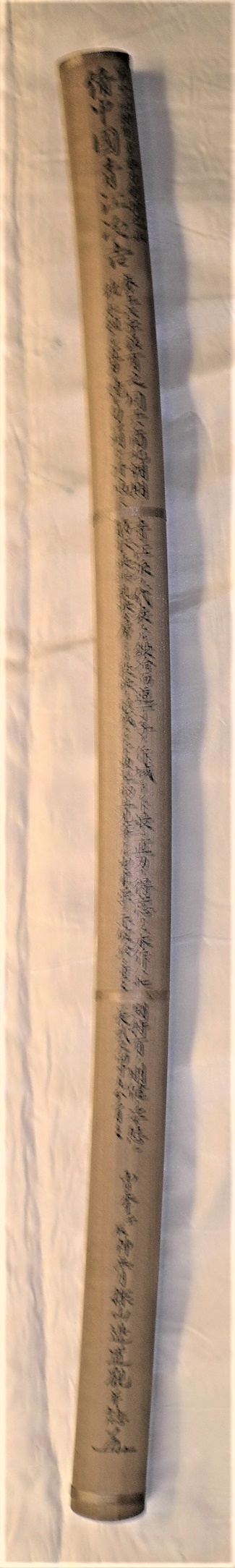

Sayagaki translation: Designated as Tokubetsu Jūyō-tōken at the 21st tokubetsu jūyō-shinsa. Bitchū (no) Kuni Aoe Tsuguyoshi. The blade is suriage, but bears a six characters signature. This smith was a representative swordsmith of the Nanbokuchō period Aoe School. Apart from a workmanship in saka-chōji, he mostly focused on a suguha. This blade has the typical vigorous shape of that time and is hardened in the smith’s typical suguha. The nioiguchi is bright and clear and the ji shows a linear and a midare-utsuri which together form a layered dan-utsuri. This work is not only very typical but also of a magnificent deki. Very rare, very precious. Blade length is 75.4cm. Examined and written by Tanzan Handō (pseudonym of Tanobe Michihiro) in tenth month of the year of the Dragon, this era (2012) and kaō.

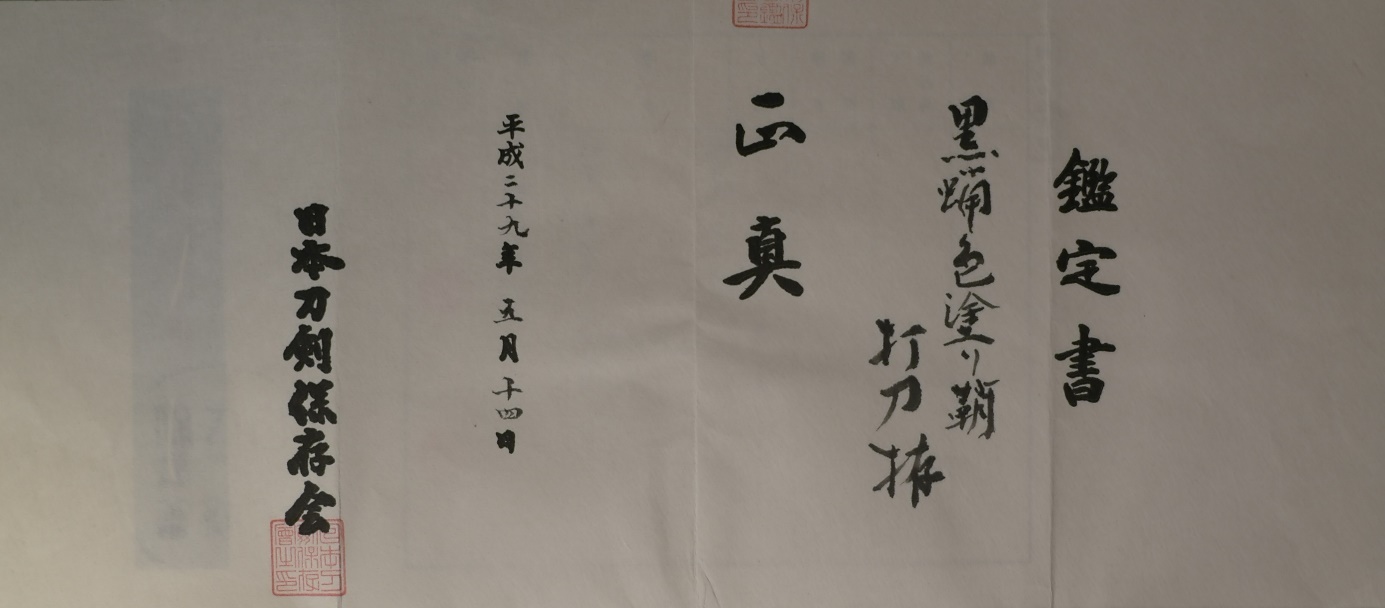

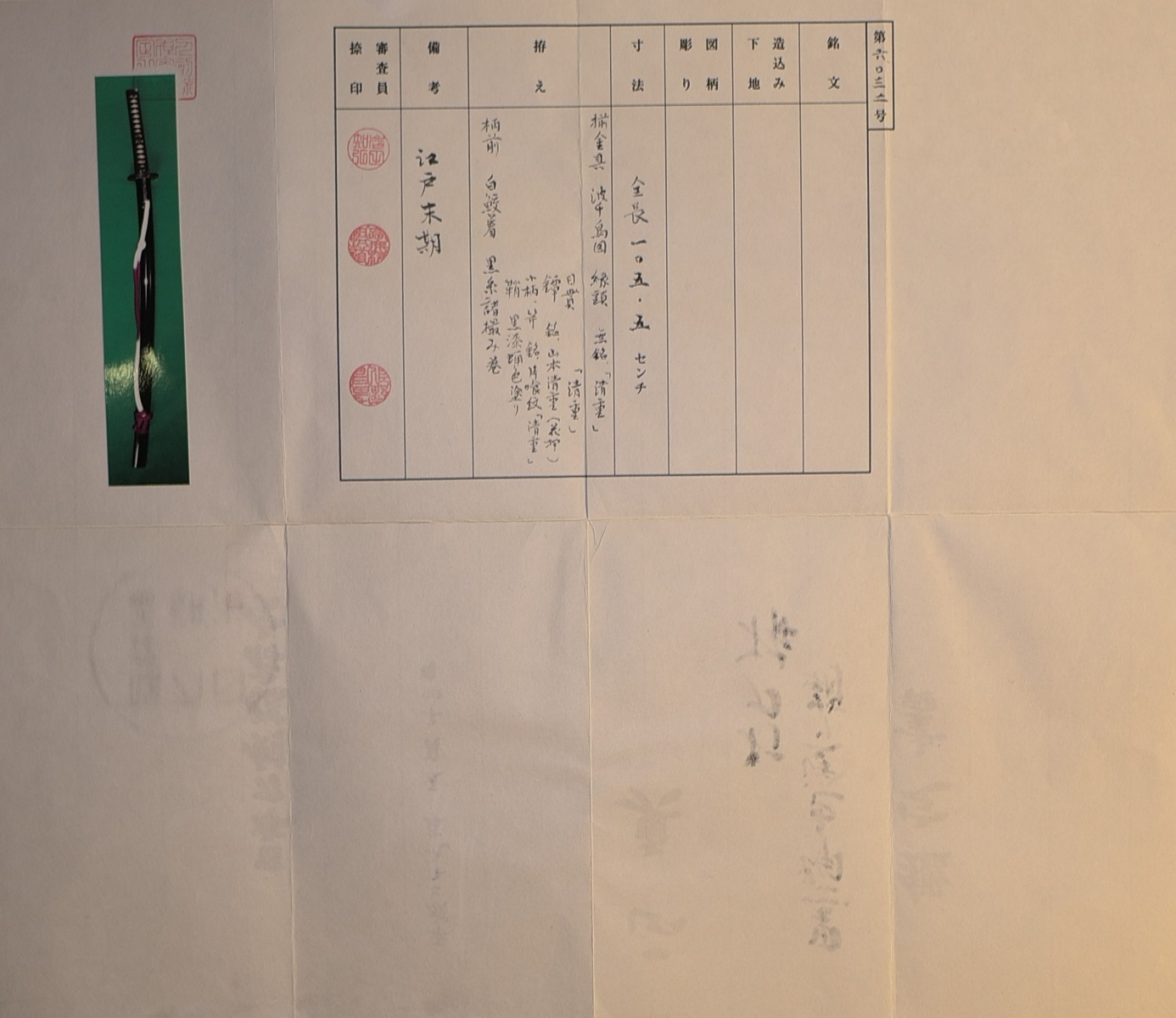

Koshirae certificate translation: Uchigatana-koshirae with glossy black-laquered saya. Shōshin (authentic). Mounting: Fitting en suite with waves and plovers motif. Fuchigashira is mumei (attributed as work of Kiyoshige); menuki are mumei (attributed as work of Kiyoshige); tsuba signed as Yamamoto Kiyoshige + kaō; kozuka and kogai are mumei (attributed as work of Kiyoshige) with Katabami crest; tsuka with white same and black moro-tsumami-maki. Mesurements: overall length is 105.5 cm. Remarks: end of Edo period.

Nihon Tōken Hozon Kai document #6032, dated 14th May, 2017.

N.T.H.K. society. Seals of Judges: 3 seals.

Translations were presented by Alexander Trykolich.

Publications:

Bushi no Bi (武士の美) by Kashima, Okayama prefecture, 1988, #10, p.19. (Catalog of the exhibition, held on March 23, 1988 in the Ibara-city (井原市), Okayama (岡山) Prefecture). Dai Tōken Ichi catalogue, 2008, p. 11. Dai Tōken Ichi catalogue, 2009, p. 135. Dai Tōken Ichi catalogue, 2010, p. 56.

Figure 3. Bushi no Bi (武士の美) by Kashima.

Figure 4. Dai Tōken Ichi catalogue, 2010, p. 56.