The first generation Sōshū Masahiro (相州正廣) came onto the scene in the end of the Nambokucho period and was able to re-establish the Sōshū Tradition and started the line of the Masahiro swordsmiths existed until 7th generation which continued the tradition of the Sagami School to end of the Muromachi period. According to available records, Sōshū Hiromitsu had two sons: Hiromasa (広正) and Masahiro (正広). Some sources, such as the Mekiki Hyakka Jō (目利百ヶ條), state that Masahiro also signed later with the name Hiromitsu, using a very similar signature style. In this connection, his work may be confused with that of his father.

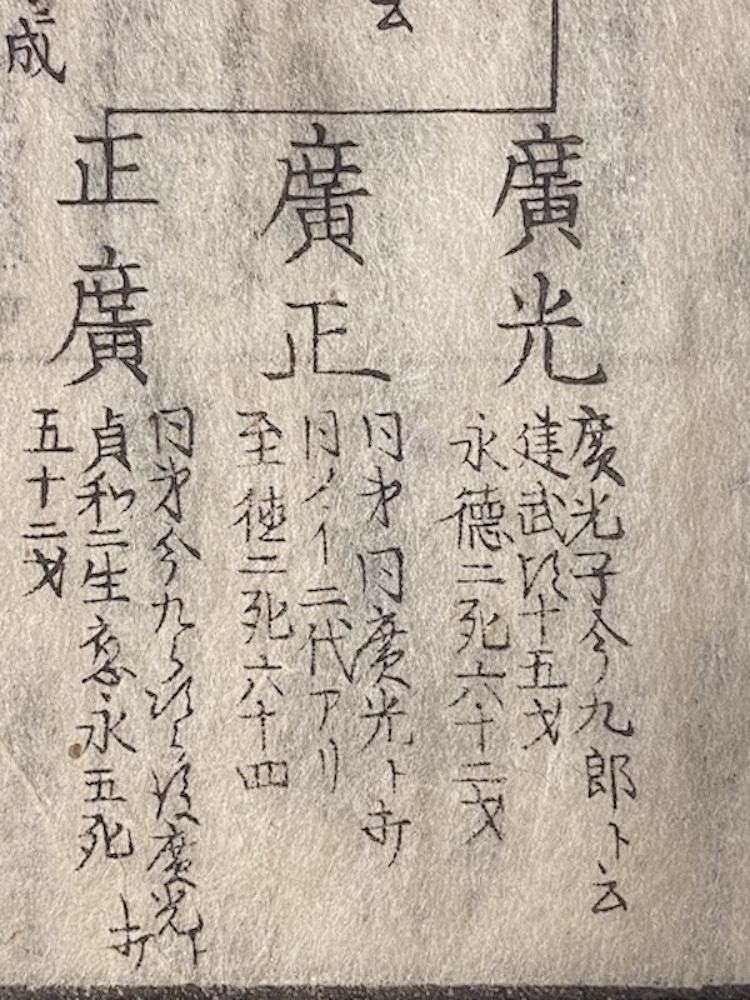

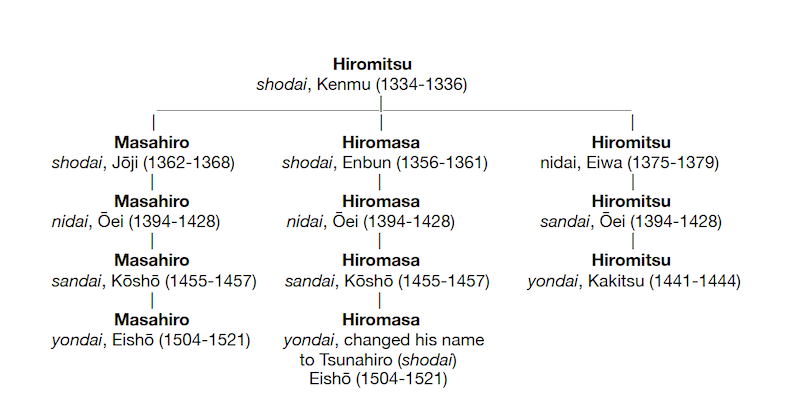

The Kotō Meizukushi Taizen (古刀銘盡大全) indicates Hiromitsu genealogy line as followed:

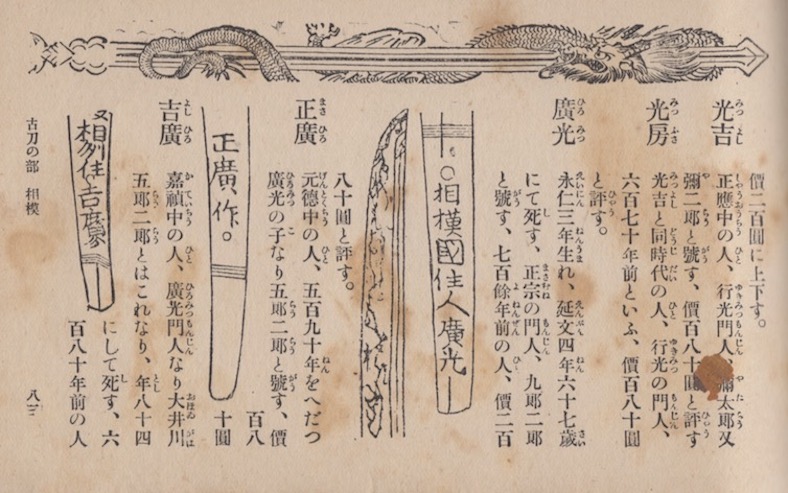

Figure 1. Kotō Meizukushi Taizen, Volume 2, p. 12/2.

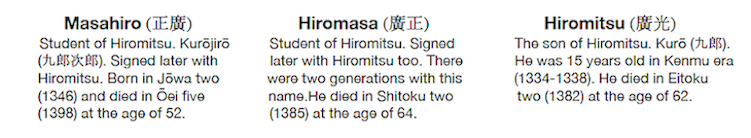

According to other sources, such as the aforementioned Honchō Kaji Kō (本朝鍛冶考), Masahiro’s date of birth is seems to be a little bit early: "Masahiro during the reign times of the Emperor Go-Daigo (後醍醐天皇 Go-Daigo-tennō, November 26,1288 – September 19, 1339) and eras Gentoku (元徳, 1329-1331) and Shōkyō (正慶, 1332-1334), a son of Hiromitsu, Gorōjirō (五郎二郎), after his father’s death he also used the name of Hiromitsu later when signing his swords. He was active during Ōei (應永, 1394-1428) era."

Figure 2. Honchō Kaji Kō, Volume «Tiger», p. 6/1.

In other words, we can find here another interpretation of the period when Masahiro was born. If we assume that the data of the Honchō Kaji Kō are correct, then the opinion of Uchida Soten regarding the one who was actually Masahiro’s father is very important. Uchida Soten (内田疎天) in his book Dai Nihon Tōken Shinkō (大日本刀劍新考), 1939 tells us that Masahiro was actually the son of Masamune. Thus, it it quietly possible that Masahiro (1st generation) was initially taught by Masamune. Later, Masahiro was trained by Hiromitsu and it was under his guidance Masahiro became proficient in hitatsura techniques. Masahiro is considered as one of the founders of so-called Sue-Sōshū (末相州) group of the swordsmiths.

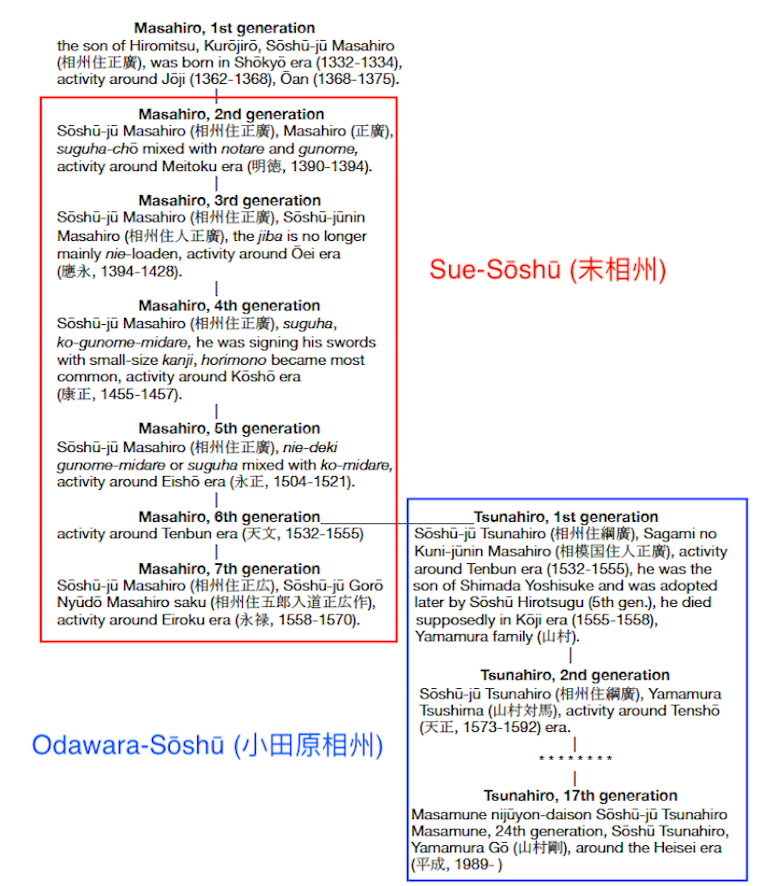

As it was mentioned above, Masahiro genealogy line was continued till 7th generation. However, it is said that around Tenbun (天文, 1532-1555) era, 6th generation Masahiro was founded Tsunahiro (綱廣) genealogy line. Old manuscripts tells us that around the Tenbun era Masahiro was invited by Hōjō Ujitsuna (北条氏綱, 1487 – August 10, 1541) who was the lord of the Odawara (小田原) castle. Masahiro and his workshop had worked exclusively for Ujitsuna producing swords to meet with increasing demands of Hōjō clan samurais. Probably Masahiro changed his name after giving him kanji «Tsuna» from the own name of his lord Ujitsuna. Thus, of existing works by Tsunahiro are, substantial, strong and massive swords and it is rare to meet the swords made with hitatsura techniques implementation. Tsunahiro is considered as one of the founders of so-called Odawara-Sōshū (小田原相州) group of the swordsmiths. Any case, one could find a strong connection between Hōjō clan and Sagami School swordsmitn. Even that Hōjō Ujitsuna is a representative of so-called Go-Hōjō clan his clan has a direct connection with old Hōjō regents family ruling the Kamakura capital during the end of Kamakura period.

Hōjō Ujitsuna (1487-1541)

Hōjō Ujitsuna was the son of Hōjō Sōun (Ise Shinkurō), who is considered as a founder of the Go-Hōjō clan. Ujitsuna changed the generic name Ise to Hōjō, appealing to the inheritance of the ancient Hōjō family, former owners of Izu province lands. Subsequently, Hōjō Ujitsuna married a representative of the ancient Hōjō clan, after which his claims to the clan name became legal. In 1522 the Uesugi clan troops attacked and burned Kamakura, which was a major loss to the Hōjō symbolically, because the earlier Hōjō clan from which they took their name fell in the siege of Kamakura in 1333. Over several years before his death in 1541, Ujitsuna oversaw the rebuilding of Kamakura, making it a symbol of the growing power of the Hōjō, along with Odawara and Edo.

Hōjō (Ise) Sōun (1432-1519)

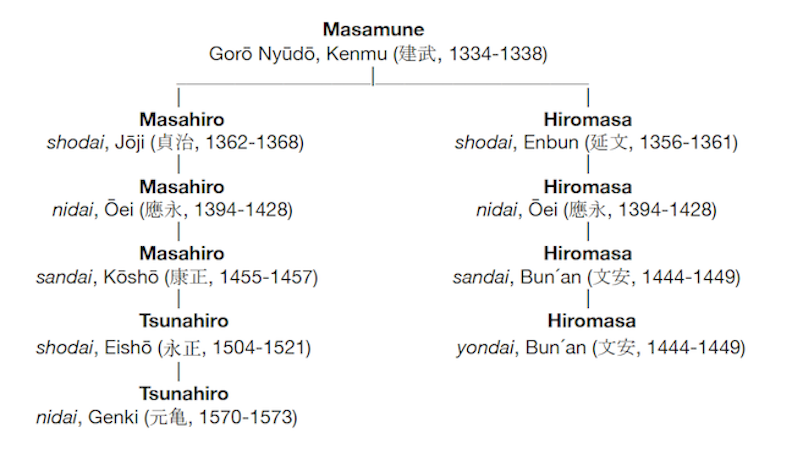

The genealogical lines of Masahiro (Sue-Sōshū) and Tsunahiro (Odawara-Sōshū) could be presented as followed:

Apparently, Masahiro (1st generation) was the representative the main line of the Sagami School swordsmiths. In this case, we can completely understand the logic of how Masahiro’s smith name was formed from the first kanji of Masamune’s name and the first kanji of Hiromitsu’s name. Taking into account his strong connections with Kamakura and Hōjō family it is possible to suppose that he was a head of Sagami School after Hiromitsu and Akihiro. In addition, a very important sword has been preserved, which indicates the possible usage by Masahiro an alternative kanji for writing «Masa» character to sign his works. This sword is dated: "the 11th month of 1362" and signed as: "Sōshū Kamakura-jū ??hiro". The "Masa" kanji is partially missing and in the NBTHK interpretation could be reading as 政. It is said that this alternative "Masa" kanji used Masamune for signing his works.

Ishida Kirikomi Masamune (石田切込正宗) was marked by an extremely interesting fact: on the old box dating back to the early Edo era, in which the sword was stored, there was an inscription: “Ishida Masamune” with the name Masamune written as 政宗. This corresponds to another smith, whose name was also spelled Masamune (see the table on the page 112 in the JAPANESE SWORDS: SŌSHŪ-DEN MASTERPIECES).

The Kokon Tōken Binran (古今刀劍便覧) by Matoba Chokei (的場樗渓), tells us that: "Masahiro was born in the middle of the Gentoku era (i.e. in the 1330th year). He was active around 590 years ago (i.e. around the 1347th year). He was the son of Hiromitsu and his name was Gorōjirō (五郎二郎). Valuation: 180 yen." (Examples of valuation for different Sōshū smiths in this book can be presented as followed: Yukimitsu = 600 yen, Masamune = 730 yen, Sadamune = 600 yen, Akihiro = 400 yen, Hiromitsu = 280 yen).

Figure 3. Kokon Tōken Binran, Tokyo 1937, p. 83.

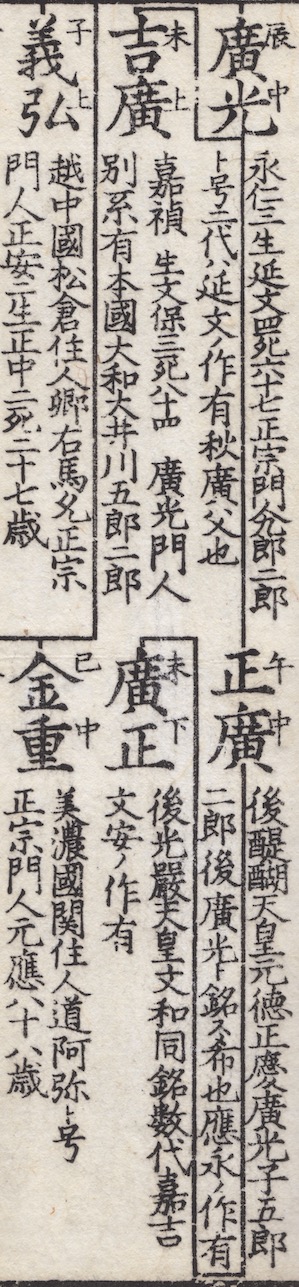

There are two more variants of Masahiro genealogy line:

Figure 4. The Masamune genealogy.

Figure 5. The Hiromitsu genealogy.

Masahiro’s surviving works are very rare, especially made by Masahiro first generation. Currently, we know of only five of his works of the Jūyō level and one sword with the status of Jūyō Bijutsuhin. Overall, just six swords made by this master (who presumably worked for a sufficiently long period of time) have survived until our time. Moreover, this is the only Jūyō Bijutsuhin Masahiro notorious for being on the list of “Missing Swords During the Occupation” by Albert Yamanaka (Albert Yamanaka’s Nihontō Newsletter, Volume 3, pp. 239–252, San Francisco, 1994–2004). We can find here: "Designated: September 24, 1941; Type: Tachi; Lengh: 25 3/4 inches - 2 shaku, 1 sun, 6 bu; Inscribed: "Sōshū-jū Masahiro" (相州住正廣); Particulars: The blade was submitted to the Tsuchiura Police of Ibaragi Prefecture by the owner on the 1st of October of 1945. The blade was turned over to the US Occupation along with Item 9,10 & 11." [i.e. four swords was submitted to police by the owner and met they fate together; we can find note regarding item 9: on October 8, 1945, the Tsuchiura Police turned the blade over to Lieut. Col. Nataniel Ward, Commanding Officer of 637 Tank Destroyer Battalion].

All of the above mentioned works still have a signature, and most are also dated in addition. Yet these preserved signatures and dates allow us to conclude that NBTNK faced a difficulties attributing swords to Masahiro's work if they are unsigned. Among the swords, having categories below Jūyō, attributed to Masahiro, of course there may be unsigned works. However, at the moment this analysis is not possible. The reasons for the current situation are unknown, especially that there are signed and dated examples of Masahiro works which are indisputable examples that can be used as a standard. Perhaps, Masahiro was a smith who always signed his swords, whose works have survived to this days are extremely few, whose swords were originally forged short-sized with a signature located relatively high to machi line.

Masahiro and Sue-Sōshū School

The Northern and Southern Courts period, spanning from 1336 to 1392, was a period that occurred during the formative years of the Muromachi bakufu of Japanese history. The Nanbokuchō turbulent time was the war between loyalists who wanted the Emperor back in power, and those who believed in creating another military formation modelled after Kamakura. During this period, there existed a Northern Imperial Court, established by Ashikaga Takauji in Kyōto, and a Southern Imperial Court, established by Emperor Go-Daigo in Yoshino. Kamakura has lost its significance as the capital city and the center of swordsmithing art. This happened immediately after the Kenmu Restoration in 1336. This process had its direct negative consequences for the Sagami School.

It seems quite natural that the changes that occurred in Kamakura’s status and the rising instability in this region completely destroyed the current atmosphere of creativity in Sagami and in other schools. As a result, many smiths who had worked with Masamune and other great masters of the school moved to other provinces:

- Norishige and Gō Yoshihiro returned to their native province of Etchū,

- Samonji moved to the island of Kyūshū,

- Rai Kunitsugu and Hasebe Kunishige went to Kyōto,

- Kaneuji and Kinjū moved to the province of Mino, and

- Chōgi and Kanemitsu returned to the province of Bizen.

Among the Sōshū masters who belonged to the main line, only Hiromitsu and Akihiro did not leave Kamakura. There is available information proving that Hiromitsu was poor (see the corresponding chapter on this smith in the JAPANESE SWORDS: SŌSHŪ-DEN MASTERPIECES). This testifies to the difficult financial situation of the school, and keeping up the previous tempo of its development was hardly possible. It is obvious that the very elements that initially formed the strength of the Sagami School soon contributed to its weakness. Probably, Sagami School forge factory based during the Nanbokuchō times in the so-called Sōshū native settlement: Yamanouchi (山ノ内). Masters like Masahiro (正廣), Hiromasa (廣正), Hirotsugu (廣次, activity: Bunna, 1352-1356), Yoshihiro (吉廣, activity: Kōan, 1361-1362), Sukehiro (助廣, activity: Kōryaku, 1379-1381) were among those who working in Yamonouchi during the Nanbokuchō period together with Hiromitsu, Akihiro and their direct descendants.

It is believed that the Sue-Sōshū period begins with the second generation of Masahiro. It was at this time that part of the Sōshū smiths moved to other provinces. For example, starting from Fuyuhiro (冬廣): moved to Obama (小浜) in Wakasa (若狭) province, ending by Hiroyoshi (廣賀): moved to Hōki Kurayoshi (伯耆国倉吉) in the Daiei era (大永, 1521-1528). However, the border line dividing the traditional Sagami School and Sue-Sōshū School is a significant change in the forging technology used by a master for producing his works.

Originally, the Sōshū-Den method was more technically difficult and time-consuming to produce than the other methods in the forging technique, such as tempering works especially. It was impossible more for smiths at the end of the Nanbokuchō period to strictly adhere to the tanren and steel preparing rules of the Sōshū-Den. Generally, Sue-Sōshū smiths still focused on the gunome-midare with tight nioiguchi and hitatsura but the swords lost both the nie and some others characteristics features of the Sōshū-Den. This so-called fourth and fifth periods of the Sagami School development was the last bastion of the original Sōshū Traditions during Muromachi period. The main feature of these periods is a very sparse nie, becoming similar to nioi. Sue-Sōshū smiths at the end of the Muromachi period started to follow more the Shimada (島田) School practice and accepted some of Shimada’s forging techniques ( hitatsura hamon, big and standing out togariba, and muneyaki).

Sue-Sōshū works have the following distinguishing features:

Sugata: swords dimension became shorter than early and we can see a little saki-zori shape.

Kitae: the jigane became hard, small and densely grained. The grains are coarse and hada is tightly ko-mokume. The itame-hada (the unique Sōshū-Den characteristic) is not seen more.

Hamon: in the late works there is not much seen in a chōji style, and the hamon became gunome hamon. The hamon is in o-midare style made in hitatsura. On the first glance the blade is made in nie as it looks flamboyant but activity resulting from nie is very scarce (or without nie activity at all) and nioi is most common. Hamon line sometimes accepted the tempering line of the Ōei era Bizen-Den style.

Bōshi: the boshi made in midare-komi style with the pattern different of one side from another or pattern that is losing its shape. Yaki-kuzure with deep kaeri is the most common type.

Horimono: the horimono became one of the most important characteristic feature of the Sue-Sōshū period. Kurikara, ken, bonji are engraved and made in gyō or sō styles. There are a lot of variants of hi, such as bō-hi and bō-hi accompanied with soebi.

Nakago: the nakago is made in tanagobara-gata style and short usually. The tip is in kengyō-jiri style. Yasurime is kiri. Signatures is made by the small or medium size kanji.

Original content Copyright © 2020 Dmitry Pechalov