Shizu Saburō Kaneuji (志津三郎兼氏) is one of those smiths who are the most challenging to study and who followed, in their time, the Sagami School’s tradition. His numerous moves to different locations, modifications in his smithing style, the change of the kanji used in his signature, and the long period of his creative activity—all this makes it very difficult to attribute his works. Therefore, it is important to clearly define all the stages of the master’s creativity to understand the periods to which his particular works belong.

Kaneuji’s place of origin is considered to be the village of Yurugi (動木) in the vicinity of the town of Nara, Yamato Province. According to the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen (古刀銘盡大全), during the Gen’ō era (元応, 1319–1321), the master was in his 36th year; he was born in the 7th year of the Kōan era (弘安, 1284); and he died at the age of 60 in the 3rd year of the Kōei era (康永, 1344). Kaneuji had been trained and began to work as a smith at the Tegai School (手掻). According to some sources, his teacher was Tegai Kanenaga (手掻包永). Kanenaga, whose middle period of creative activity is defined as the time span from 1288 to 1293, is considered the founder of the Tegai School. Kaneuji’s year of birth, as specified in the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen, fully matches the years of Kanenaga’s activity. Moreover, in the early stage of his work, Kaneuji signed with two kanji 包氏, writing the first kanji 包 in the same manner as Kanenaga. Such continuity in using this kanji can be considered a confirmation of the relationship that existed between Kanenaga and Kaneuji. Unfortunately, it appears that no swords signed with 包氏 have survived (more on this later). We can draw conclusions about the nature of the signature and the similarity of writing the kanji only based on extant pictures and records in old oshigata collections.

As a book, the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen is very important and interesting, in that it contains the birth and death dates of all the smiths described therein. However, not all of the dates provided are accurate; the book has some erroneous data. Unfortunately, Kaneuji’s exact birth and death dates are unknown; therefore, the information provided in this source is indispensable and virtually the only one on which we can rely. Hence, we should also take into consideration that this source mentions two generations of Kaneuji, since we know that some of his works are dated after 1344.

In the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen, we can find oshigata of Kaneuji’s swords dated the 1st year of the Kan’ō era (観応, 1350) and an unknown year of the Enbun era (延文, 1356–1361)—the ordinal number of the year is unreadable. Hence, the theory that possibly the 1st generation (shodai) of Kaneuji was directly trained by Masamune seems quite reasonable. To date, there are few extant works by this master. In this case, the 2nd generation (nidai) of Kaneuji is a successor and pupil of shodai Kaneuji.

As for the composition of “Masamune no Jittetsu,” it should be noted that at different times, various sources considered Kaneuji either among the best of Masamune’s pupils or not in this category. The first source that mentioned Kaneuji among Masamune’s ten best pupils was the Mei Zukushi Hiden Shō (銘尽秘伝書, 1625). The list of the best ten pupils was drawn up in the early Edo period, and the author of the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen believes that Kaneuji was trained directly by Masamune. It should be admitted that this point of view is the most well-founded. Among all the smiths mentioned in the “Jittetsu,” Kaneuji most accurately and closely reproduced the style of Masamune’s works, in all their details and nuances. Many researchers, including Dr. Honma and Albert Yamanaka, call Gō Yoshihiro, Norishige, and Kaneuji the best three smiths from “Masamune no Jittetsu.”

It should also be noted that in old books of the Momoyama period (1573–1615), such as one by Takeya Ri’an (竹屋理安, 1579), the Shinkan Hiden Shō (新刊秘伝抄, 1573–1592), and the Funki Ron (粉寄論, 1596–1615), Kaneuji is not called a pupil of Masamune and is not mentioned among the smiths of “Masamune no Jittetsu.” Based on this, many experts—primarily, Fujishiro Yoshio—believe that Kaneuji did not study directly under Masamune, and that he merely was highly influenced by the Sōshū School in the process of moving from Yamato to the province of Mino.

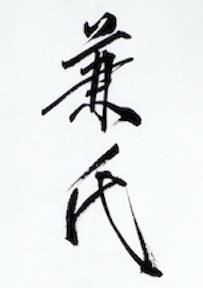

It is known that during the Gen’ō era (元応, 1319–1321), Kaneuji left his native province of Yamato and traveled to the village of Nokami (野上) in the region of Fuwa (不破), Mino (美濃) Province. But before his arrival at Mino, he had spent some time in Kamakura, working there and studying new techniques. It is unknown how long the master stayed there, but immediately after he left Kamakura, he changed the way he wrote the first kanji (“Kane”) of his smith’s name from 包 to 兼. It can be noted that in the changed form, this kanji was written in the so-called Mino style. We do not know for sure when Kaneuji started to sign his name as 兼氏, because dated extant works of this master are very rare. Based on much indirect evidence, we can assume that this change took place when the master was staying in Mino, rather than in Kamakura.

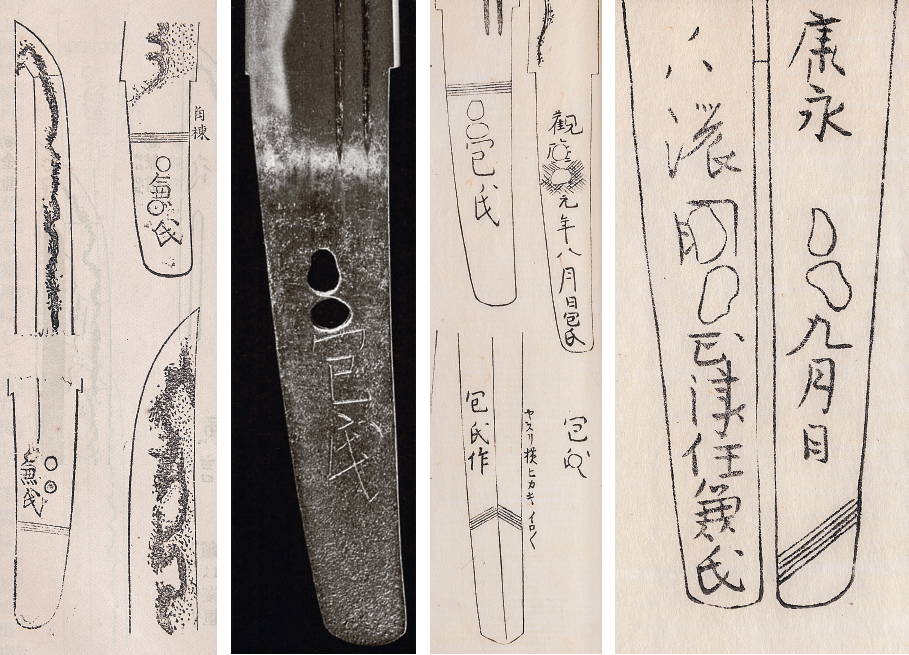

Despite the fact that precious few extant signed swords by Kaneuji have survived to our time, there are enough of them to enable us to draw conclusions about the master’s stages of creativity. In particular, it is not quite accurate to state that no swords signed by Kaneuji using the version 包氏 have survived. It would more correct to say that, to date, there are no extant swords of the master’s first generation with this type of signature (i.e., the earliest version of the signature that the master used to sign his work during his time in Yamato Province). Currently, there are 4 works signed with 包氏. All of them were created by the 2nd generation, and all of them are tantō: Jūyō Nos. 24, 29, 37, and Tokubetsu Jūyō No. 10. The work Jūyō No. 24 is dated in the year 1362, and Jūyō No. 37 is dated in the year 1356. There are many more swords by the master signed with these kanji: 兼氏. Currently, we know of 3 tantō (Jūyō No. 31, Jūyō Bijutsuhin No. 246, and Jūyō Bunkazai) and 5 tachi (Jūyō Bijutsuhin Nos. 244, 245, and 3 Jūyō Bunkazai). As for the long signature, there is an extant tachi (Jūyō Bijutsuhin No. 247) signed in the naga-mei style: “Mino (no) Kuni-jūnin Kaneuji” (美濃国住人兼氏). In addition, there is an oshigata of the sword dated the 9th month of the year of (unreadable) of the Kōei era (康永, 1342–1345) and signed “Mino (no) Kuni Shizu-jū Kaneuji” (美濃国志津住兼氏)—see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Oshigata with a signature by Kaneuji. Tōken Kantei Hikketsu, Hon’ami Yasaburō 1905, Part Kotō, Volume 5, p. 41; Tantō Yamato Shizu Kaneuji, Tokubetsu Jūyō No. 10; Kotō Meizukushi Taizen, Volume 8, p. 19/1 and p. 26/1.

In 1335, Kaneuji once again relocated his smith shop, having moved to the village named Shizu (志津) or Shizuyama (志津山) in the region of Tagi (多芸), Mino Province. Later, Kaneuji’s followers and pupils moved to the village of Naoe (直江), which adjoins Shizu from the north. Among these pupils, we can find, first of all, the names of Kanetoshi (兼俊), Kanetomo (兼友), Kanetsugu (兼次), and Kanenobu (兼信), who most likely were Kaneuji’s sons or close relatives. It is with these masters that one associates the emergence and the development of the school that later was known as Naoe-Shizu (直江志津).

<.....> Speaking of Kaneuji’s role in creating the Mino School’s smithing tradition, we have to mention two other masters: Kinjū and Tametsugu, who worked at about the same time. Kinjū (金重), who moved to Seki (関), Mino Province, largely contributed to the development of the Mino-Den. The master studied the Sagami School techniques; therefore, he carried out his experiments in combining several forging styles in the same direction that Kaneuji did, based on the methods and practices that he studied in Kamakura. Unfortunately, there is no exact data on whether the two masters ever met or whether they worked together, but they were the ones who laid the foundations of the Mino tradition—one of five Gokaden schools that prospered until the end of the Muromachi period.

Their personal contact seems to be improbable, because the dates of the main activity of shodai Kinjū fall in a slightly earlier period than that of shodai Kaneuji. However, many sources tell us that these two masters jointly founded the Mino School—as if they worked at the same time and in the same shop. Yet this was not the case, and we should bear in mind that Kaneuji and Kinjū followed two quite different trends of the Mino tradition; they worked in different places and periods of time. Although the time span of their activity can be defined as the early Nanbokuchō period, Kinjū’s activity falls during a somewhat earlier period.

Fujishiro Yoshio, in his book Nihōn Tōkō Jiten, mentioned two masters named Kaneuji, stressing that they were different smiths. The first one—Yamato Shizu Kaneuji—is ranked jōjō-saku (上々作, a very high level of craftsmanship) and was Kanenaga’s pupil. The second one—Shizu Saburō Kaneuji—is ranked saijō-saku (最上作, the highest level of craftsmanship) and, presumably, was Masamune’s pupil, although Fujishiro denied this.

This is another example of the unending confusion with respect to this master. Therefore, in regard to any work associated with the name Kaneuji and his school, we must be very careful when reading the description provided by NBTHK or any other organization that issued the document. In addition, we need to pay extra attention to the sword design itself and the features of the forging techniques used in its manufacture.

Currently, NBTHK uses three types of attribution: Yamato Shizu, Shizu, and Kaneuji. Yamato Shizu includes works made by Kaneuji in the Yamato style. We can simply consider them to be items manufactured in the period before he was trained by Masamune or, at least, before he experienced significant influence from the Sagami School. This is a rather large category, consisting of numerous works: 102, including 99 Jūyō and 3 Tokubetsu Jūyō (100 long and 2 short swords). The same category also includes works by the Yamato Shizu School’s smiths who stayed in the province of Yamato and continued working there in the Yamato style after Kaneuji himself left.

The Shizu category includes works made by Kaneuji after he passed his training in the Sōshū School’s techniques, either directly under Masamune or with other masters during the period when he lived in Kamakura. These swords show features that combine the Yamato and Sōshū traditions, with a prevalence of the latter. This is the most numerous category, consisting of 141 swords, including 120 Jūyō, 14 Tokubetsu Jūyō, 6 Jūyō Bijutsuhin, and 1 Jūyō Bunkazai (112 long and 29 short swords).

Finally, the Kaneuji category includes works attributed to both the first and the second generation of Kaneuji and either signed by the master himself or having Hon’ami kinzōgan-mei or Hon’ami shu-mei. Such works are not numerous: to date, there are 23 items (14 long and 9 short swords), including 13 Jūyō, 1 Tokubetsu Jūyō, 4 Jūyō Bijutsuhin, and 5 Jūyō Bunkazai. We should note that in this category, the ratio of long to short swords is most typical of the Kotō smiths, whereas in the two former categories, we can see a clear preponderance of long swords.

Summing up this data, we can say that currently, there are 266 works of the Jūyō category and higher, whose attribution is related to Kaneuji. It seems impossible to calculate how many other swords have Hozon, Tokubetsu Hozon, and Kichō attributions and papers by organizations other than the NBTHK. Thus, it is rather unlikely that such a huge number of works were made by one master, even in two generations and taking into account the works of his pupils and followers that were also included in these categories. Besides, in some situations certain works initially attributed to Masamune were later re-attributed as Shizu. That is why Kaneuji is one of the most complicated categories of smiths who were connected with the Sagami School. <.....>

The main features of works by Kaneuji are as follows:

Sugata: Early tachi and katana feature a standard Kamakura sugata, a normal mihaba, a chū-kissaki, a small toriizori, funbari, and an iori-mune. Swords made in the pure Yamato style are characterized by a high shinogi. Later works have features of the Nanbokuchō period with a wide mihaba, an ō-kissaki, and an iori-mune (a high or medium one); we can also find katakiri-zukuri works with mitsu-mune. Tantō are usually of a short length, muzori, and sometimes uchizori; all tantō have mitsu-mune.

Jitetsu: A good-quality ko-mokume with areas of ō-hada and itame-hada. In the area of shinogi-ji, we can see the manifestation of masame-hada, chikei, plenty of nie, which are sometimes of a large size; the steel is characterized by a blackish color that is typical of Mino-Den.

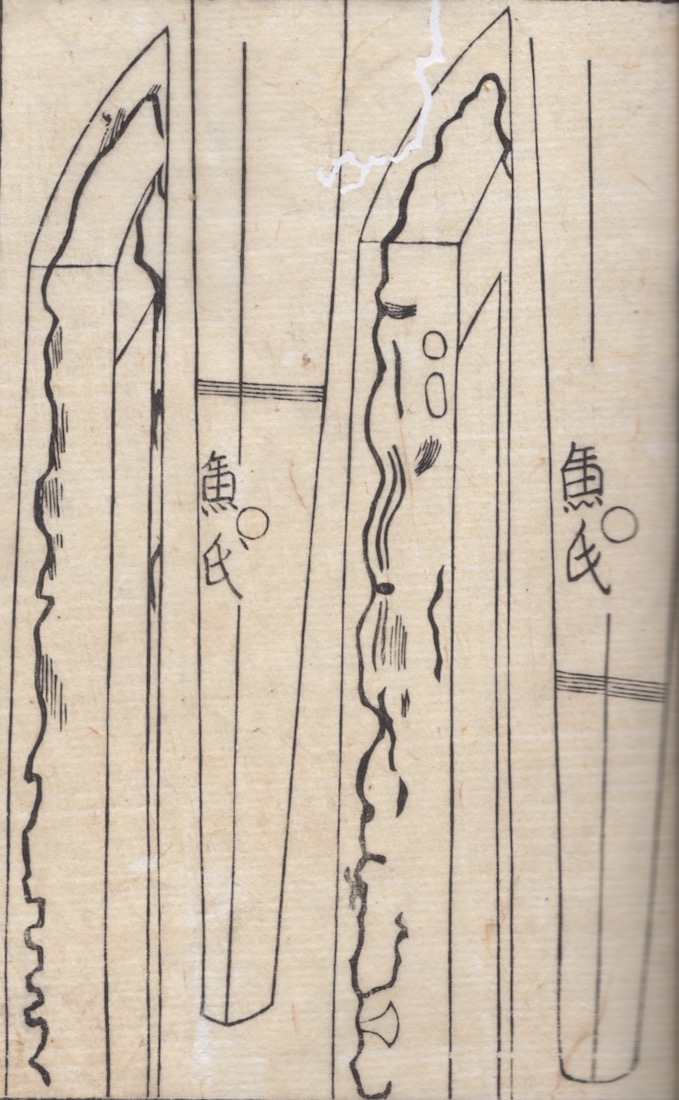

Hamon: Mainly, gunome or notare; sometimes a combination of the same. Nie-deki, and sometimes we can see thick nioi. Plenty of nie, ara-nie, often kuzure, inazuma, and kinsuji; high activity of the hamon. The works in the Sōshū Style feature a slightly deeper notare; there are some manifestation of togari-ba.

Bōshi: Midare-komi, with a slight kaeri; a light ō-maru; we can see a small togari and also a small hakikake in the area of the tip.

Horimono: We can find bō-hi and futasuji-hi on katana and tachi; tantō can feature suken and koshi-bi.

Nakago: It is believed that there are no genuine tachi and katana with an ubu nakago; in old oshigata, the nakago features a slight sori. Tantō: The presence of muzori and slight furisode, the tip of the nakago is usually ha-agaru kurijiri, and yasurime features small katte-sagari.

Mei: The signature consists of two kanji; on tantō, it is located directly under the mekugi-ana; the size of the kanji is slightly larger in the late period. There is some roundness in the style of writing the “Kane” kanji in works by nidai Kaneuji.

Figure 3. Kaneuji's elements of activity layout. Kokon Meizukushi Taizen, vol. 5, p. 20/1.

(excerpt from Chapter 15, pp. 346-363, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces )

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov