According to information contained in old manuscripts, Kaneshige (金重) was born in Tsuruga (敦賀), Echizen Province (越前). The most common, typical form of his smith name is the so-called Chinese transcription—Kinjū. His father was Motoshige (元重), who in 1229 came to Seki (関), Mino Province (美濃), from the settlement of Hibara (檜原), located in Hōki Province (伯耆). The Kotō Meizukushi Taizen (古刀銘盡大全) indicates that Motoshige was named Rokurōzaemon (六郎左衛門) and shared his smithing knowledge with Kinjū. As indicated in the same book, during the Gen’ō era (元応, 1319–1321), Kinjū was in his 88th year, as he was born in the 1st year of the Jōei era (貞永, 1232) and died in the 2nd year of the Genkō era (元享, 1322), in the 91st year of his life.

In the early period of his creative activity, Kinjū worked in the style of the Senjū’in School and was a Buddhist monk in the Seisen-ji (清泉寺) temple, located in Echizen Province. His Buddhist name was Dōami (道阿弥). Sometimes we also encounter his other monastic name—Keiyū (慶友). At that time, smiths from Buddhist temples who made weapons for warrior monks worked in the Yamato tradition; therefore, Kinjū forged his early works in the pure Yamato style. Perhaps the reason Kinjū did not sign his early works was that his works of this period were originally intended for warrior monks.

In the old book Ōseki Shō (p. 28; reprint, 1978), there is an entry stating that Kinjū was a very skilled horimono engraver; he engraved in a style similar to Yamato’s and different from Bizen’s.

There are no extant swords by Kinjū’s father, Motoshige. Most likely, it was a mistake to think that Motoshige worked in the Seki style and was the founder of this school. Traditionally, it was Kinjū, not Motoshige, who was considered the founder of the Ko-Seki School (古関). In this connection, we should note that some authors question whether Kinjū’s paternity should be attributed to Motoshige or to someone else. There are some grounds for this suspicion. One of them is from information in old manuscripts (the link can be found in Uchida Soten’s studies) stating that Kinjū had not been trained in smithing from childhood. At first, he was a merchant, and only at a more mature age did he start forging and later become Masamune’s disciple.

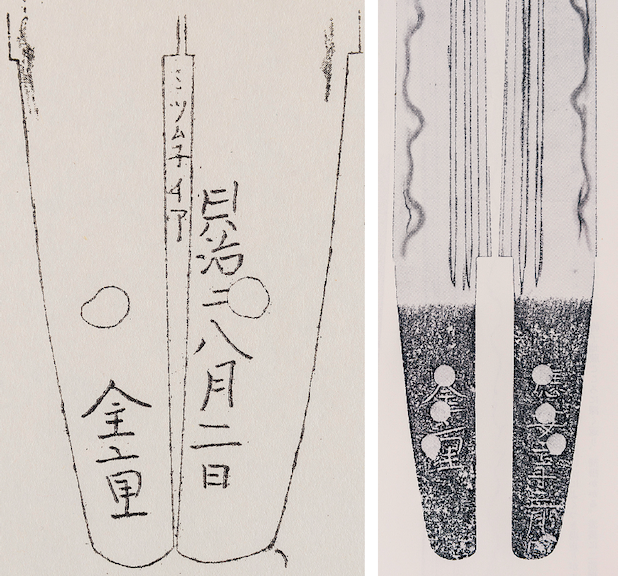

Figure 1: Nakago oshigata of Kinjū’s daitō. Kokon Meizukushi Taizen, Volume 6, p. 17/2 (left) : nakago oshigata of Kinju's tantō, signed and dated (1363) on the same side. Kōzan Oshigata, Volume 2, p. 39/1 (right).

The Kotō Meizukushi Taizen states that Kinjū came to Sagami Province in the 61st year of his life, in the 5th year of the Shōō era (正応, 1292), in order to learn new forging techniques at the most influential and impressive school (at that time), the Sōshū School. However, for unknown reasons, that same year he left Sagami and returned to Mino Province. We should point out that these two provinces are located fairly close to each other, and the distance between their capitals, Gifu and Kamakura, is only slightly more than 160 miles. Then Kinjū came to Kamakura for a second time, during the Ōchō era (応長, 1311–1312). In 1311, he began to study with Masamune. His teacher was 48 then, while the trainee was 82 years old. Numerous old sources refer to Kinjū as Masamune’s disciple and one of “Masamune no Jittetsu.” It was after his training at the Sōshū School when the first signed swords by Kinjū appeared. Naturally, they were made in the Sōshū-Den style. In Kamakura, the master worked for about five years. We can see that the years mentioned in the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen differ slightly from the alleged periods of other disciples’ training with Masamune. It should be noted that the time of both the first and the second appearance of Kinjū in Sagami (1292 and 1311) are not aligned with Masamune’s position as a teacher but instead with Shintōgo Kunimitsu’s.

According to the same source, after finishing his work and studying in Kamakura, Kinjū returned to Seki. Here, he founded the Seki School, which eventually branched out extensively, taking a prominent place in the history of smith art in Mino Province. With the formation and development of this school, Kinjū significantly contributed to the creation of the last of the Five Schools of Japanese Swordsmiths (Gokaden): Mino-Den. He is rightly considered one of the founders of the Mino traditions. This particular school absorbed the forging traditions of Sōshū and combined them with Yamato traditions. Apart from Bizen, which suffered a great setback at the end of the Muromachi period when the flooding of the Yoshii River almost entirely destroyed Osafune, Mino became the most successful and influential direction in the world of Japanese smiths for the next 600 years. In our time, the city of Seki, in Mino Province, remains a major center of sword- and knife-making. The Mino tradition became the basic principle followed by masters working in the times of Shintō, and smiths from this province dispersed throughout Japan, spreading their knowledge and skills everywhere.

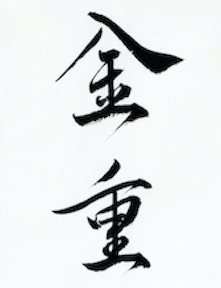

There is little information about Kinjū’s works, and few of his works have been preserved. Among his signed works, only a few tantō are known, as well as numerous oshigata that can be seen in old collections. According to these sources, Kinjū signed with two kanji—金重. Swords made before the very end of the Kamakura period did not survive, because most Yamato-style works were made by monk-smiths who did not sign their works as indicated. They might have simply been lost among the works of other masters because of their great similarity in style. Dr. Honma Junji considers a signed tantō from the Koizumi Tomitarō collection to be Kinjū’s earliest extant work. This tantō (Jūyō No. 20) has a nagasa of 29.7 cm, is in hira-zukuri, and shows an itame-hada and a midare-hamon with elements of hitatsura. According to some reports, the sword was named “Dambira Kinjū” (i.e., “broad Kinjū”). This tantō by Kinjū was made at the end of the Kamakura period or at the very beginning of the Nanbokuchō period. It certainly testifies to its author studying directly with a grand master in the Sagami School and perhaps even with Masamune himself.

Currently, most experts agree that there were two generations of smiths who worked under the name Kinjū. It is believed that Kinjū, representative of the eldest (shodai) or 1st generation (presumably, 1233–1322), was Masamune’s disciple. However, most of his swords were done in the Yamato style and did not survive to the present day. Nevertheless, it is possible to note that certain appropriate dates might “make” him Masamune’s disciple. The Kotō Meizukushi Taizen also notes that Masamune was 28 years old when Kinjū first came to Kamakura and was 48 during Kinjū’s second visit. It is hard to imagine that a representative of Kinjū’s 1st generation worked before the beginning of the Nanbokuchō period, bearing in mind that the assumed year of his birth is 1233. The only surviving tantō, described above and attributed by Honma Junji to Kinjū, has all the characteristics of the Sagami School. These characteristics allow us to conclude that at the end of his career, shodai Kinjū produced swords in the Sōshū style with unequivocal signs of learning from one of the grand masters of this school. However, because this tantō is not dated, the exact time of manufacture cannot be determined, so assigning it to the beginning of the Nanbokuchō period, given the entire set of data on the 1st generation, can be questioned. Most likely, it was manufactured before 1322.

Shodai Kinjū signed with two kanji and probably did not date his works at all. The extant old oshigata make it hard to conclude what style they were forged in. Almost all these oshigata are tantō tang images. Therefore, it is also impossible to unambiguously state whether the master signed his long swords.

The 2nd-generation (nidai) Kinjū apparently worked from the beginning of the Nanbokuchō period onwards, and a small number of his dated works have survived. The earliest of them is dated the 2nd year of Jōwa (貞和, 1346); moreover, some oshigata of his swords have survived.

Figure 2: Oshigata of Kinjū’s signature. Kōzan Oshigata, Volume 乾, p. 33/1; Kantō Hibi Shō, Supplement No. 2, p. 92.

In old books, the period of Kinjū’s 1st-generation creative activity is indicated as Shōō (正応, 1288–1293), and the 2nd-generation creativity as Jōwa (貞和, 1345–1350) and Jōji (貞治, 1362–1368). We should note that in later books, the duration of the 1st-generation creativity was moved to a slightly later period—the Gen’ō era (元応, 1319–1321). It seems somewhat artificial and apparently was changed in order to more closely match the theory that Kinjū directly trained with Masamune.

The works of Kinjū’s successors, especially Kaneyuki (金行), Seki Kanemitsu (兼光), and Kanetoshi (兼俊), perfectly comply with the dates of the 2nd-generation’s activity. Through Seki Kanemitsu, we can possibly trace Kinjū’s kinship with Kaneuji. In old books, such as the Ōseki Shō (p. 28; reprint, 1978), it is stated that Kanemitsu was married to the daughter of Kinjū, and Kaneuji was his uncle.

However, we should realize that the existence of only two generations of smiths signing as Kinjū is probably oversimplified, as there could be several more of them.

When assessing and attributing swords as Kinjū’s works, there are some features and complexities involved:

- First, Kinjū’s swords are not ranked higher than the Jūyō status. Despite his high skill level and fame as one of the founders of the Mino traditions, this smith has the jōjō-saku (上々作—very high level of skill) rating, in accordance with Fujishiro’s system. This is slightly lower than the usual top-ranking smiths who are directly related to the Sagami School;

- Second, in the modern NBTHK assessment system, there is often no clear indication of the time period in which a work by Kinjū was produced and consequently, to which generation of master it belongs. The NBTHK simply indicates the attribution of unsigned and undated swords as “Kinjū”;

- Third, the NBTHK very often made an attribution with a “Den” prefix. Thus, about 52 percent of Kinjū’s swords are indirectly attributed to him with the “Den” prefix.

Currently, there are 44 works with Jūyō Tōken status that are attributed to Kinjū. These include 29 long swords (katana and tachi), 8 wakizashi (5 of them are ko-wakizashi; in the old oshigata, they are denoted as tantō), and 7 tantō. Such a small number of extant swords might indicate a great demand for this master’s work for actual combat use, which subsequently led to the ruin, loss, and destruction of his swords during Japan’s long history of wars and conflicts. <.....>

According to Uchida Soten’s (内田疎天) records, Kinjū’s swords exhibit the following main features:

1. A katana has an obtuse-angled iori-mune and is hardened in the form of suguha or midare, although hardening in the midare style is more common. The kasane is thin, and wakizashi show an average sori size. Kinjū made a large number of hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi and large-size sunnobi-tantō, which had mitsu-mune. His ji-hada is typical for the Seki School. The ji-hada resembles Nobukuni’s swords, but the bōshi is different. Works in the style of suguha are similar to Nakajima-Rai’s but differ in the ji area. Kinjū’s swords often have horimono of various kinds, and the bōshi has a long kaeri, typical of the Seki School; the bōshi also has a tendency to hakikake.

2. The ha area is usually not very wide and has a structure similar to yarn—a thin, repeatedly twisted thread. This type is called “Kinjū no ito” (金重の糸), lit. “Kinjū thread” accordingly, referring to the subtle weave.

3. The steel has a color typical of the Seki School; however, the forging method applied here is typical of Kamakura blades. Many blades are wide and have non-standard shapes.

4. A fukura in the kissaki area is smooth, with slight rounding; the kitae has the itame structure; yasurime-kiri; the nakago tip is made in the kurijiri type; niji-mei; many swords have futasuji-hi.

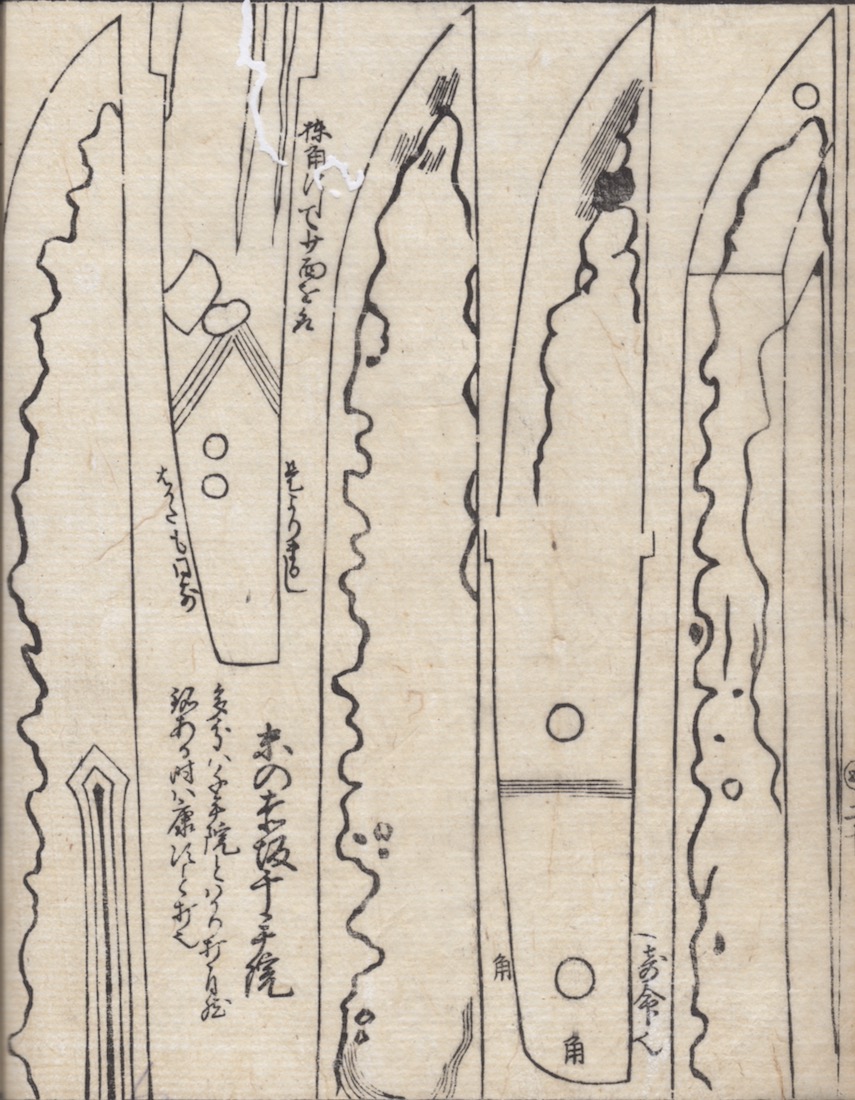

Figure 3. Kinjū's elements of activity layout. Kokon Meizukushi Taizen, vol. 5, p. 20/2.

(excerpt from Chapter 14, pp. 332-343, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces )

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov

Figure 4. Photo was made on the Gifu Prefectural Library Exhibition of Mino Swords 10/09/2019.