Sadamune (貞宗), Kenmu (建武, 1334-1338), Sagami, hi signed as „Sagami no Kuni-jū Sadamune“ (相模国住貞宗), he came according to transmission originally from Ōmi province and borne the first name „Hikoshirō“ (彦四郎), in Kamakura he became the student and later adopted son of Masamune (正宗), but he is not listed as one of the „Ten Students Masamune“ even if he followed Masamune ́s style most closely. There are oshigata of signed blades in old manuscripts with date signatures from the Kagen (嘉元, 1303-1306) to the Jōwa era (貞和, 1345-1350). There are no zaimei works exists which could be definitely attributed to him. Tokaido (東海道), saijō-saku.

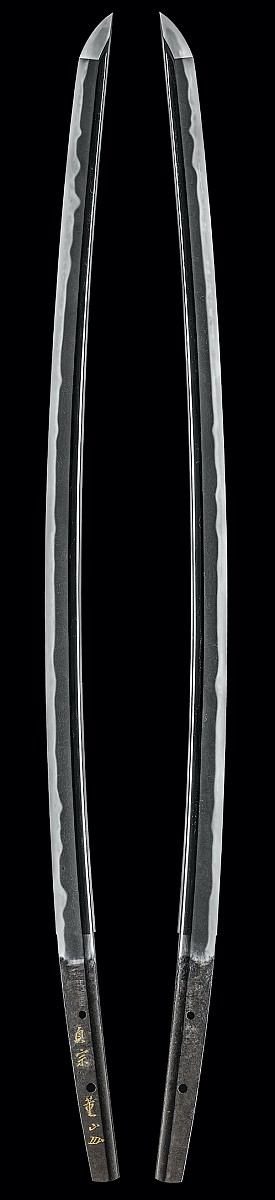

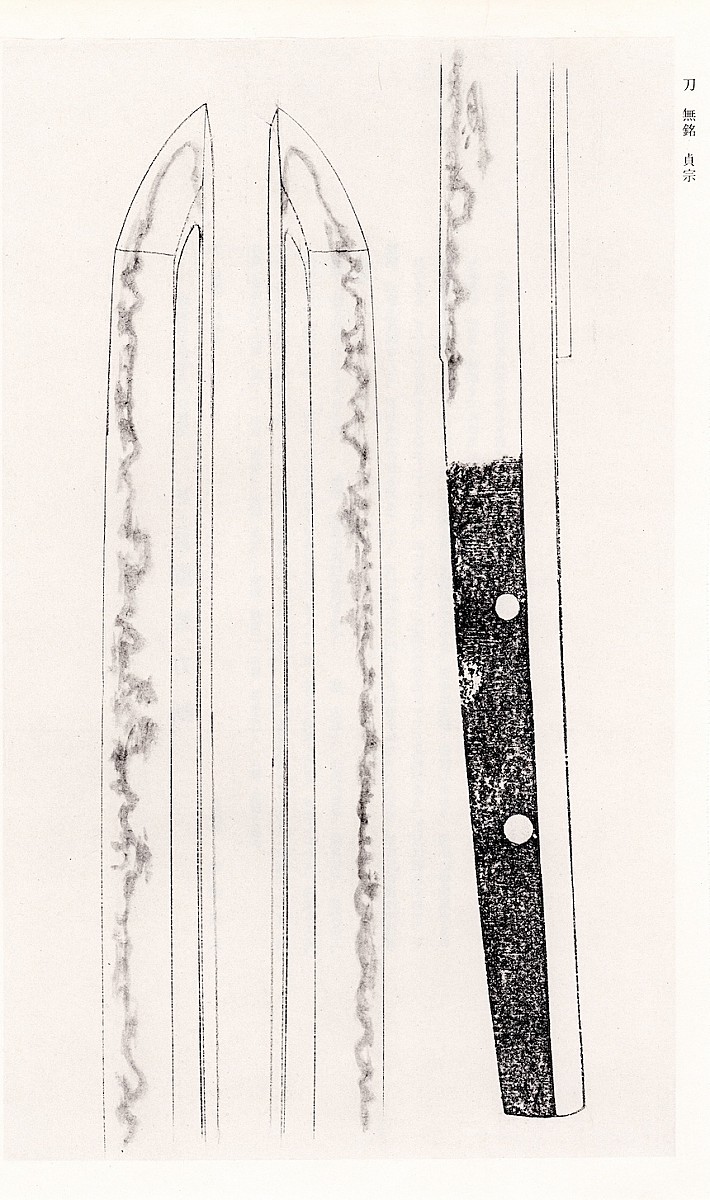

Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken "Bo-hi Sadamune": nagasa: 69.6 сm; sori: 1.6 сm; motohaba: 2.85 сm; sakihaba: 2.2 сm; motokasane: 0.65 сm; kissaki nagasa: 3.7 сm.

Designated as Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken at the 7th tokubetsu-jūyō-shinsa held on the 20th of November 1980.

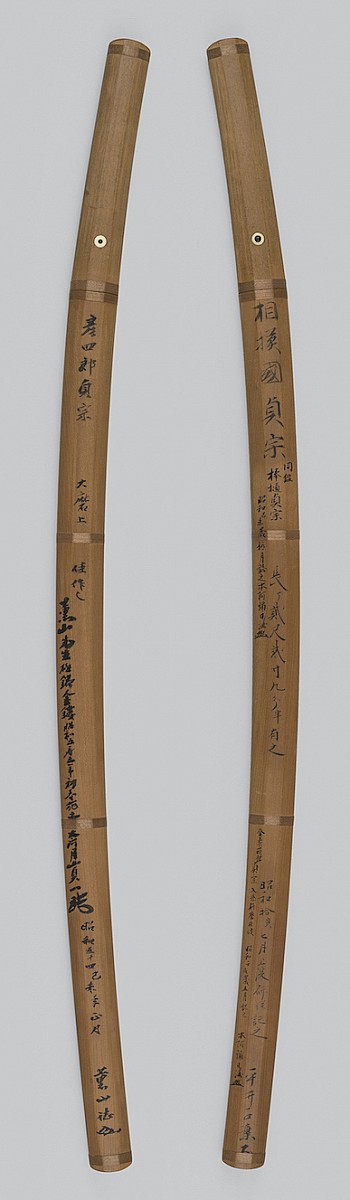

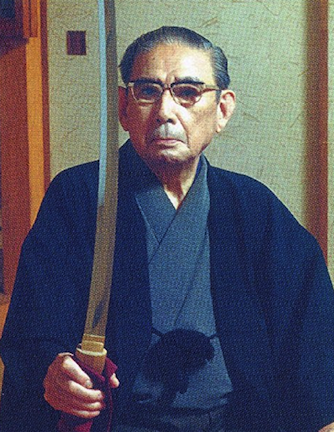

This katana is unsigned, attributed to Sadamune, meitō “Bō-Hi Sadamune” (棒樋貞宗); kinzōgan-mei Sadamune by Kunzan (Honma Junji—本間順治); made by Gassan Sadaichi (月山貞一, 1907–1995, Ningen Kokuhō); polished by Hirai Chiba (平井千葉, 1872 - 1937) in 1935; polished by Hon’ami Nisshū (本阿彌日洲, 1908–1996, Ningen Kokuhō) in 1979; origami Hon’ami Nisshū (1982), setting the value at 150 mai; sayagaki Hirai Chiba 1935; Hon’ami Nisshū 1979; Kunzan 1979; and Gassan Sadaichi 1980 (see the translation at the end of the chapter). All the above listed experts have confirmed the authenticity of the sword and its attribution to Sadamune. Provenance: Murakami Shintarō (村上慎太郎), Matsuura Tatsuto (松浦達人), and Yoshino Ichirō (吉野一郎).

Publications: NBTHK Jūyō Tōken Nado Zufu, Volume 23; NBTHK Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken Nado Zufu, Volume 7.

Presented katana is the meitō “Bō-Hi Sadamune.” It is obvious that the blade got its name from its single large groove, typical of Sadamune’s works. Concerning the hi on Sadamune’s long swords with the status Jūyō and higher, we have the following data: bō-hi are seen on 22 works; futasuji-hi, on 10 swords; and 1 sword (Jūyō No. 5) has a bō-hi on the omote side and a futasuji-hi on the ura side. In other words, it should be noted that on Sadamune’s long swords, bō-hi are found a little more than twice as often. We should also note that a significant number of famous meitō got their names from the special horimono engraved on their blades; for example, “Kikkō Sadamune” and “Futasuji-hi Sadamune” (Jūyō Bunkazai). The sugata of the “Futasuji-hi Sadamune” sword is one of the most beautiful in the history of the Japanese smithing craft. Furthermore, it serves as an example of how the sword was named after a horimono in the form of a certain type of hi. Those two swords are very similar in that regard; in a sense, one of them complements the other, filling the empty space left by the other’s absence. To date, we know of the existence only of 420 meitō swords.

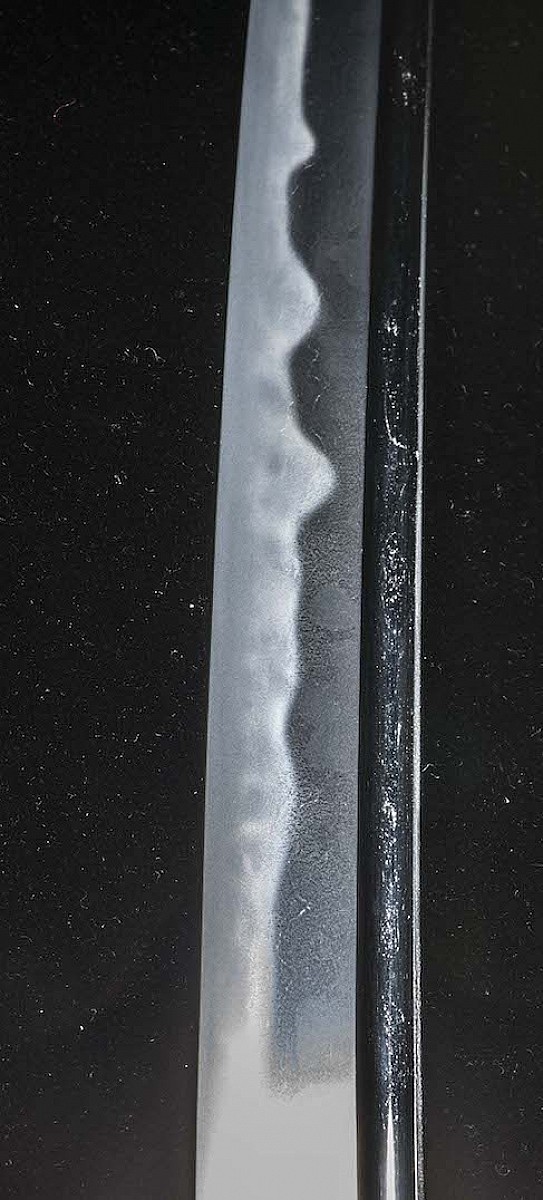

“Bō-Hi Sadamune” is one of the master’s best works that has survived to modern times, in which the blade itself is preserved in a very good and “healthy” condition, which is quite a rare occurrence. The long notare waves in some places reach even the shinogi line; in some areas, togari and chōji elements are clearly visible. A good mix of various patterns can be observed along the entire length of the blade, highlighting not only the craftsman’s impeccable artistic taste, but his ability to improve the sword’s combat-worthiness through various techniques of smithing. Yubashiri and tobiyaki are present in some areas, overlaying the hamon; they are typical for the Sagami style in the school’s heyday. The sword is a vivid and powerful representative of Sōshū Sadamune’s craft, reminding us strongly of Masamune’s work through its hamon pattern. This sword proves how hard it can be to distinguish between the works of these two masters.

In some jihada areas, the nie spots are grouped so tightly that under certain angles of light, it seems like half of the jihada changes its color. The blade shows the strongest nie-utsuri and the highest concentration of ji-nie among all the swords made by Japanese smiths. The blade has a gorgeous groove, which, judging by its clean lines and impeccable geometry, was made by a master of incomparable skill. Its nakago jiri is very old, and its appearance allows us to assume that during the Muromachi period, the blade was shortened and then went through fine and careful re-sharpening and re-polishing. The tang is decorated with kinzōgan-mei (gold engraving), confirming the sword’s attribution. Sometimes, a kinzōgan-mei was applied directly after shortening a signed sword, which led to the loss of the smith’s signature. In such cases, the master was informed of the smith who originally signed the sword, and he drew his conclusion on those grounds. In this case, however, the kinzōgan-mei was made a significant number of years later, by Gassan Sadaichi in 1980.

Figure 1. Gassan Sadaichi.

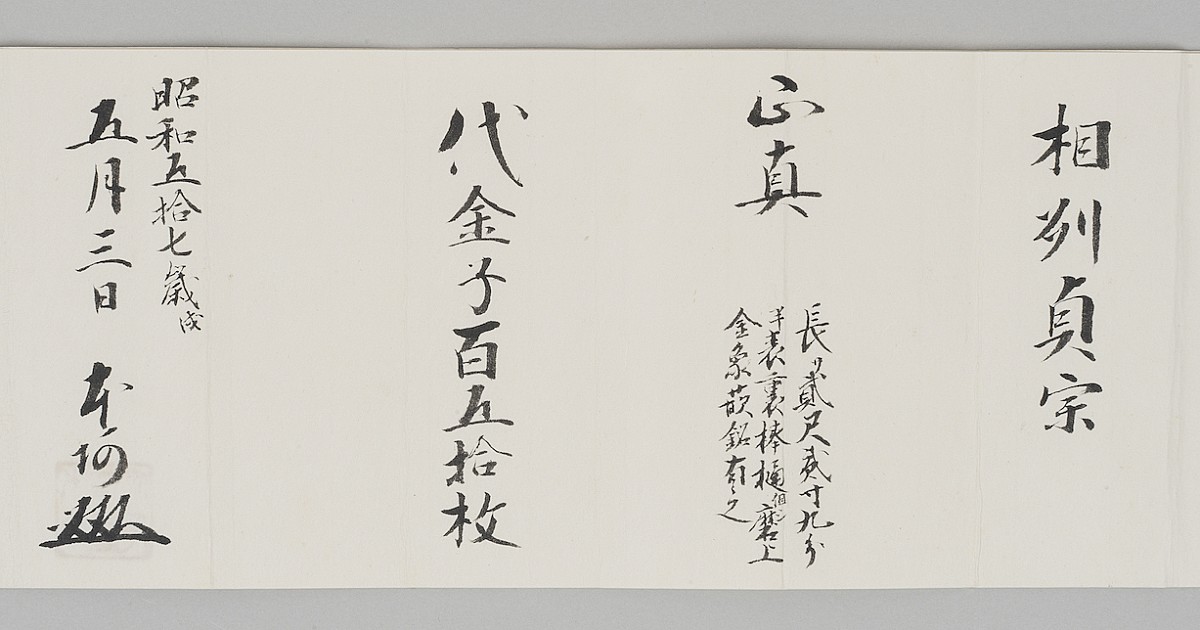

In 1982, Hon’ami Nisshū evaluated the katana made by Sōshū Sadamune and issued a certificate. Envelope Title: 相州貞宗之折紙 (Origami for a Sōshū Sadamune). Origami: 相州貞宗。正真。長サ貮尺貮寸九分。平表裏棒樋但シ磨上。金象嵌銘有之。代金子百五拾枚。昭和五拾七歳戌五月三日。本阿 [花押]。The above can be translated as follows: “Sōshū Sadamune. Authentic. Nagasa: 2 shaku, 2 sun, 9 bu. A bōhi on both sides, the blade is suriage but kinzōgan-mei kore ari—bears a kinzōgan-mei. Value 150 gold pieces (mai). May 3rd, 1982, the Year of the Dog. Hon’a + Kaō [Nisshū].”

The estimated value of the sword cited in the evaluation is denominated in gold coins used during the Edo period. As a way to honor the tradition, the Hon’ami clan used that method for evaluating the swords’ prices in their origami even many years after those coins were out of circulation.

Figure 2. Hon’ami Nisshū.

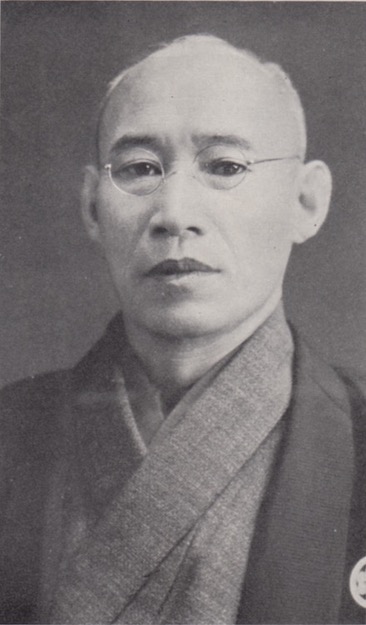

Sayagaki, made by Hirai Chiba: "Sadamune, inhabitant of Sagami. (相模国貞宗); Nagasa: 2 shaku, 2 sun, 9 bu with a half (69.6 сm). (長さ弐尺弐寸九分半有之); I polished this sword in early July, Shōwa 10th (1935), the Year of the Boar. (昭和拾亥七月上浣研候記之); Hirai Chiba + Kaō (signature with a personal monogram). (平井千葉「花押」).

Figure 3. Hirai Chiba.

Presently, “Bō-Hi Sadamune” has four sayagaki on its shirasaya: Hon’ami Nisshū; Hirai Chiba; Honma Junji (Kunzan) and Gassan Sadaichi (see all with the translations on pp.149-151 of Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces book).

In conclusion, we can outline the last eighty years of history of “Bō-Hi Sadamune.” They look roughly as follows:

- July 1935—A sayagaki, an evaluation, and a polishing by Hirai Chiba;

- July 1, 1975—The sword passes an evaluation by NBTHK and is issued a Jūyō certificate;

- January 1979—A sayagaki and an evaluation by Dr. Honma Kunzan;

- December 1979—A sayagaki and an evaluation by Hon’ami Nisshū;

- Spring 1980—A kinzōgan-mei is applied to the tang by Gassan Sadaichi;

- November 20, 1980—The sword passes an evaluation by NBTHK, as a result of which it is issued a Tokubetsu Jūyō certificate; and

- May 1982—The blade is polished by Hon’ami Nisshū, who issues a Hon’ami evaluation certificate for it.

In addition, we know the names of the owners of the collection in which this sword was included, something that is not often possible to find out. Unfortunately, we have not yet been able to establish a history of who possessed this important art object in the Edo period, as well as a more detailed history of the emergence of the sword’s name, “Bō-Hi Sadamune.” However, because of the sword’s level of mastery and the way it was carefully stored and attended to by distinguished specialists, we can assume that the clan had a very high status, as this sword was unquestionably part of the family heritage.

(excerpt from Chapter 6, pp. 132-159, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces )

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov