Norishige (則重), Enkyō (延慶, 1308-1311), Etchū – „Norishige“ (則重), „Saeki Norishige saku“ (佐伯則重作), he lived in the Gofuku (呉服) district (Gō, 郷) of Etchū province and is therefore also called „Gōfuku-Gō“, whereas at the latter nickname the character for „Gō“ (郷) is often also replaced by (江), relative many signed blades are extant and regarding date signatures, we know an oshigata from the „Umetada-oshigata“ which is dated Enkei two (延慶, 1309) and an extant tantō is dated with Shōwa three (正和, 1314), he is listed as one of the „Ten Students of Masamune“ but the known date signatures of Norishige suggest that he was rather a contemporary than a student of Masamune, in the Nanbokuchō period Ki'ami-hon mei-zukushi (喜阿弥本銘尽) we find the following entry: „student of Shintōgo Kōshin (新藤五光心)“, i.e Shintōgo Kunimitsu, that means he was a fellow student of Masamune under Kunimitsu, an approach, which is in recent years more and more accepted. Hokurikudō (北陸道), saijō-saku.

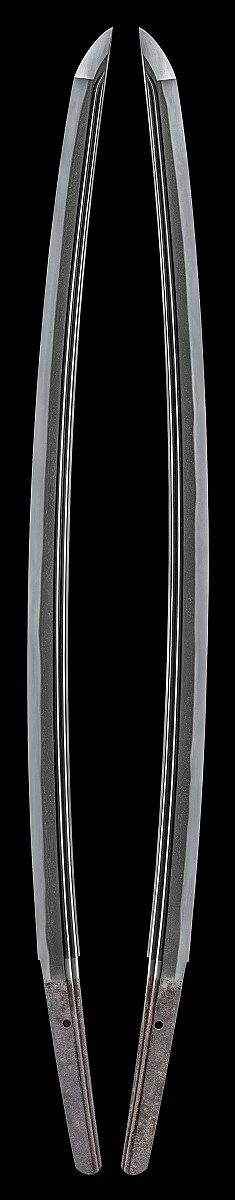

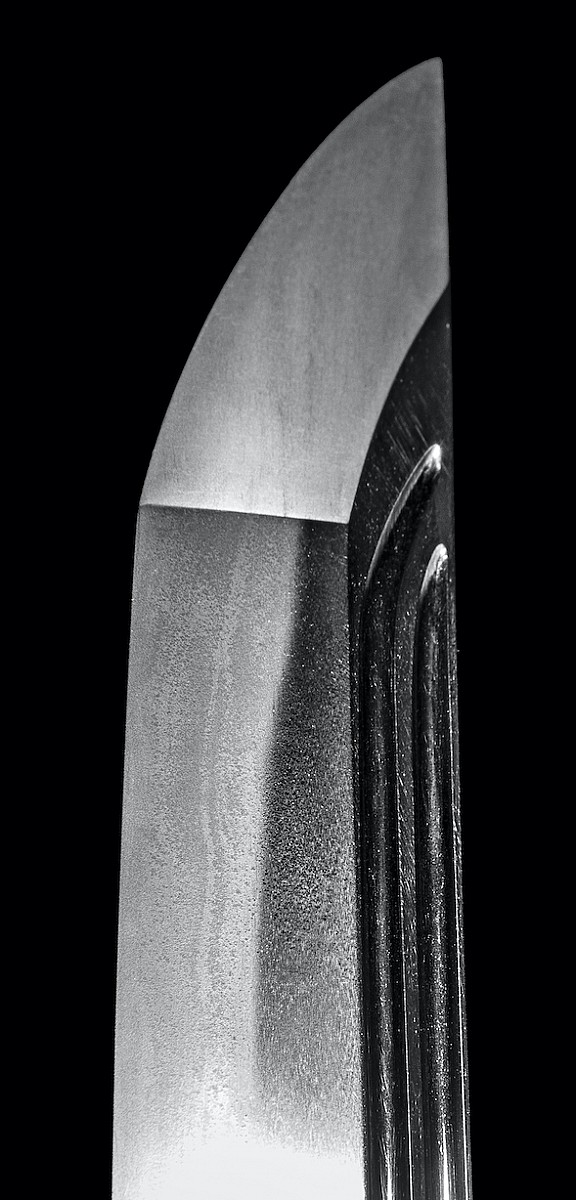

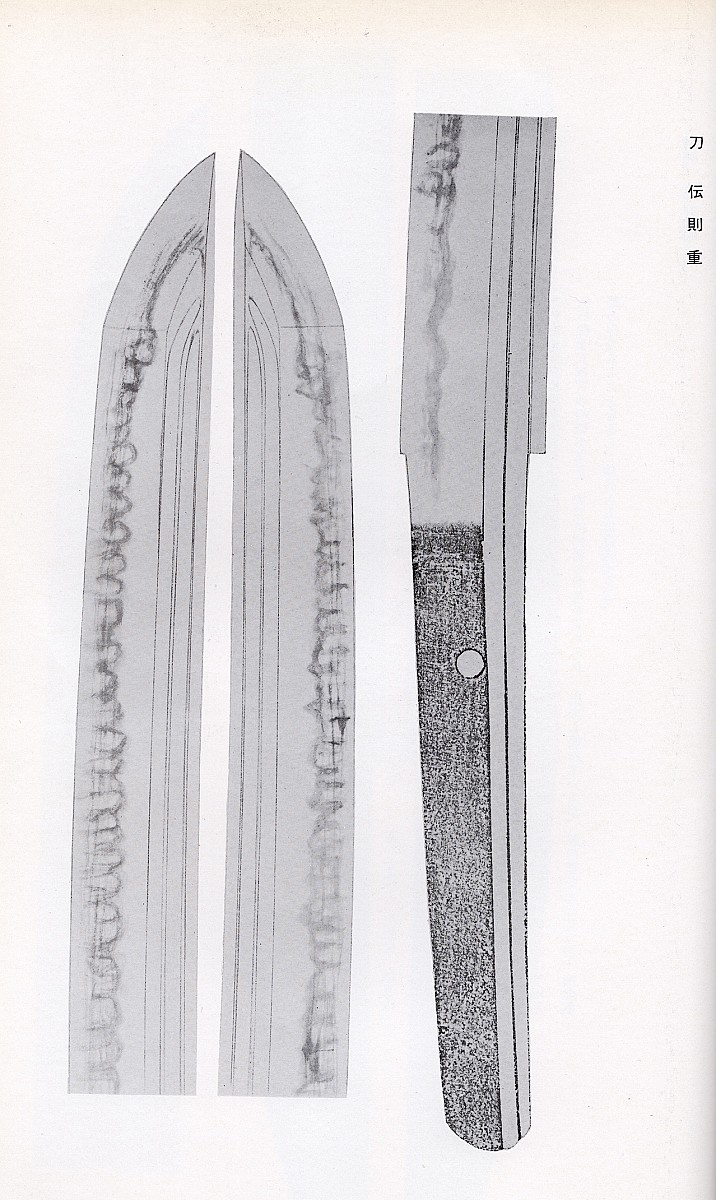

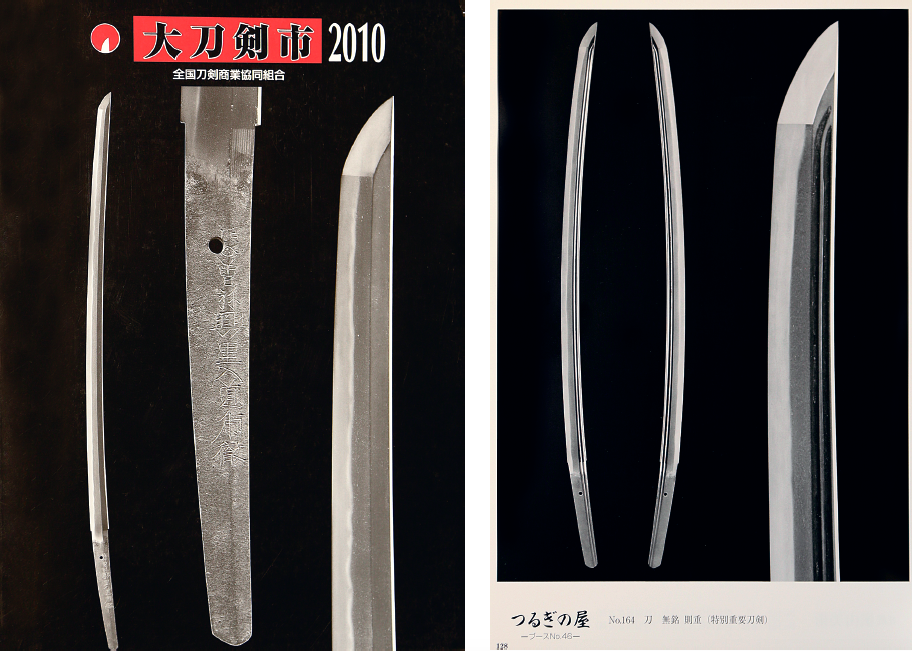

Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken Norishige Katana: nagasa: 68.3 сm; sori: 1.8 сm; motohaba: 2.9 сm; sakihaba: 2.3 сm; nakago nagasa: 16.1 сm; kissaki nagasa: 3.9 cm. This sword is ō-suriage, mumei; origami Hon’ami Kōchū (本阿弥光忠), December, 1718; evaluation by Hon’ami Kōchū 1500 kan (75 mai); tōrokushō No. 10198, issued on November 19, 1952, polished by Hon’ami Kōshū (本阿彌光洲, the 18th generation of the Ko’i line, born in 1939, Ningen Kokuhō), sayagaki on the old shirasaya Kanzan Satō (made before World War II), habaki of the sword is solid gold. Provenance: Yano Yatarō (谷野弥太郎, Kobe), Okamoto Kametarō (岡本亀太郎, Ōsaka), Murakami Shintarō (村上慎太郎), and the Kawashima (川島) family (owners of www.taibundo.com).

Designated as Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken at the 16th tokubetsu-jūyō-shinsa held on the 28th of April 2000.

Publications: NBTHK Jūyō Tōken Nado Zufu, Volume 3; NBTHK Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken Nado Zufu, Volume 16; Dai Tōken Ichi Сatalogue of 2010, p. 128.

Figure 1: Dai Tōken Ichi Сatalogue.

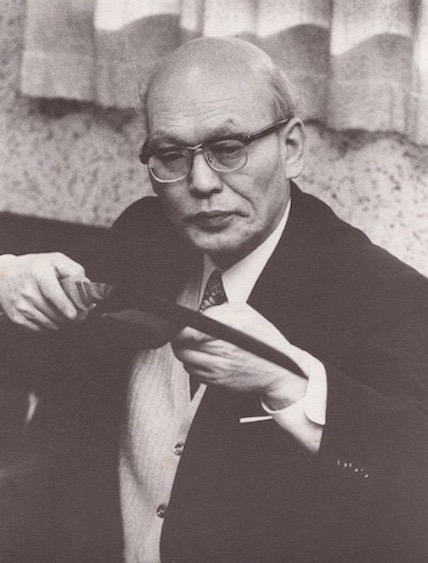

The sayagaki and the attribution were made by Dr. Satō (Kanzan) Kan’ichi (1907–1978), one of the NBTHK’s founders, who defined this sword as the work of Etchū Norishige. Satō Kanzan is one of the few teachers who preserved the tradition of evaluating and studying the Japanese sword during the Shōwa period and is the author of numerous studies devoted to the Japanese sword. It was Dr. Satō, with Dr. Honma Junji, who taught the leaders of the U.S. occupation troops after World War II about the cultural and artistic significance of Japanese swords. By explaining the difference between mass-produced army swords and a sword having cultural and spiritual value, they thereby prevented the destruction of a large number of grand masters’ works. In the 1950s and ’60s, Satō Kanzan worked as the leading expert for the Ministry of Culture of the Japanese government and NBTHK in the field of assessing, attributing, and studying the legacy of the Japanese sword.

An origami for this sword was issued by Hon’ami Kōchū in the 3rd year of the Kyōhō era (1718). The sword was attributed as Norishige’s work and was estimated at 1,500 kan. Hon’ami Kōchū was the head of the Hon’ami family from 1716 to 1736. He is known for the fact that in 1719, on the order of the eighth shōgun, Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684–1751), he completed the compilation of the Kyōhō Meibutsu Chō—a record of the most famous swords of the Kyōhō era, which included a list of all meibutsu existing at that time in Japan. The catalogue compiled by Kōchū consisted only of swords produced no later than the Nanbokuchō period. Most of the works presented in it were forged in the traditions of the Bizen and Sōshū schools, which were especially appreciated by daimyō and were very much in demand for collections. It should be noted that, of course, not all meitō entered the Kyōhō Meibutsu Chō catalogue. Some particularly valuable swords were given names, and these swords and their names were kept secretly in the clan of a daimyō for a long time. Because the names were associated with certain special historical events in the life of the clan, they were not subject to disclosure and became known only much later. No more than one hundred of these swords, among those mentioned in the catalogue, are extant.

Figure 2. Hon’ami Kōchū personal monogramm.

Norishige’s sword, presented here, has a Jūyō certificate, one of the earliest in the history of attributing swords; it is signed by Satō Kanzan himself and dated the 34th year of Shōwa (1959). This is only the third Jūyō shinsa conducted by NBTHK since its founding in 1954. In this case, it is particularly valuable and interesting that this sword was actually the first of all Norishige’s works to receive the status of Jūyō, the highest of NBTHK’s ratings at that time. The early Jūyō certificate, as well as the Tōrokushō dated 1952, confirms the unconditional value of the sword. At this time, people began to register daimyō collections, and, undoubtedly, this sword was an honored surviving item from a large and important collection. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to trace the history of who possessed this sword, except for the last several decades. This is because, according to established practice, all traces of previous owners, especially if they were well-known names or clans, were intentionally removed from documents whenever a sword like this was sold.

In the 12th year of the Heisei era (2000), the sword confirmed its attribution as Etchū Norishige and received the Tokubetsu Jūyō certificate at shinsa No. 16. To date, this is the highest status of a sword that can be legally exported outside of Japan. In the mid 2000s, the sword was considered an unconditional candidate for Jūyō Bunkazai status. As a result, it was not submitted to the tender because of the owner’s decision to sell it. The Jūyō Bunkazai status would certainly have narrowed the market of potential buyers to within the borders of Japan. Therefore, this is one vivid example of how commercial considerations interfered with the natural unfolding of a sword’s destiny.

Figure 3. Kanzan Satō photo.

The old shirasaya of the sword was made in the Meiji period and contains a sayagaki with the attribution of Dr. Satō Kanzan: 本阿弥光忠折紙。 越中国呉服郷則重。刃長貮尺貮寸五分有之。?折紙極?且一ツ謂同作中之優刀也。寒山誌。

It could be translated as follows: “with origami of Hon’ami Kōchū Etchū no Kuni Gofuku-gō Norishige. Blade length 2 shaku 2 sun 5 bu? [Agreed with] origami attribution ? and can be regarded as a masterwork among all works of this smith. Written by [Satō] Kanzan.”

(excerpt from Chapter 9, pp. 230-251, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces book)

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov