Hasebe Kunishige (長谷部国重), Kenmu (建武, 1334-1338), Yamashiro, born the first name „Hasebe Chōbei“ (長谷部長兵衛), it is said that he came originally from Yamato province where his ancestors lived in Nara ́s Hatsuse (初瀬), there exists the transmission that the family name „Hasebe“ was a modification of the pronunciation of „Hatsuse“ over „Hase“ to „Hasebe“, another theory says that he was the son of Senjū ́in Shigenobu (千手院重信), so it is assumed that his roots were in the Senjū ́in or in the Taima school, he moved to Kamakura to study as late student under Shintōgo Kunimitsu (新藤五国光) before he finally settled in Kyōto/Yamashiro, this is supported by the transmission that Kunimitsu too born the family name „Hasebe“, some even assume that Kunishige was the son of Shintōgo Kunimitsu. Kinai (畿内), jōjō-saku.

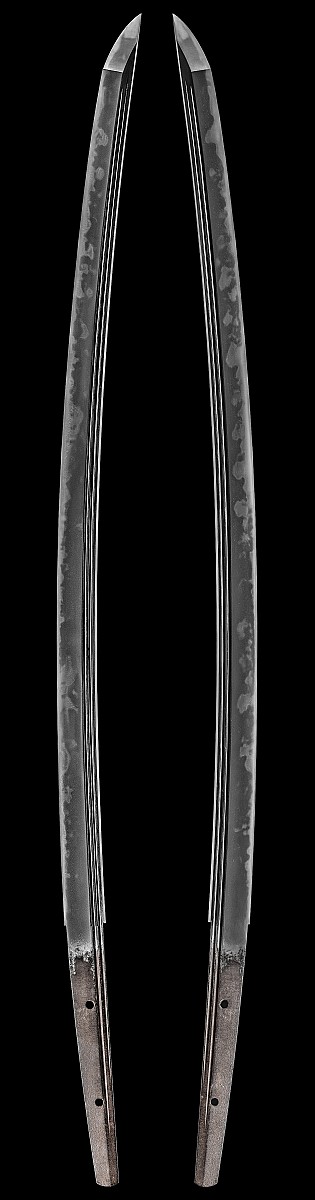

Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken Hasebe Katana: nagasa: 63.5 сm; sori: 1.7 сm; motohaba: 2.75 сm; sakihaba: 2.15 сm; motokasane: 0.65 cm; nakago nagasa: 18.9 сm; kissaki nagasa: 4.2 cm. This sword is without a signature, attributed to “Hasebe” by the NBTHK, and attributed to “Hasebe Kunishige” by Kanzan Satō; the sword was polished in sashikomi (差し込み) style by Fujishiro Matsuo (1914–2004, Ningen Kokuhō). A sayagaki on the old shirasaya was added by Kanzan Satō in April 1970 (translated at the end of the chapter). A family heirloom of the Katsurada (桂田) clan from the city of Kanazawa (金沢), Ishikawa Prefecture (石川). It was given to the Katsurada clan by the Daishōji Maeda clan (大聖寺前田). The sword was in the collections of Murakami Shintarō (村上慎太郎), Araya Kumakichi (新家熊吉), Kuroda Masashige (黒田政重), and Miyabo Kenji (宮保健治).

Designated as Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken at the 7th tokubetsu-jūyō-shinsa held on the 20th of November 1980.

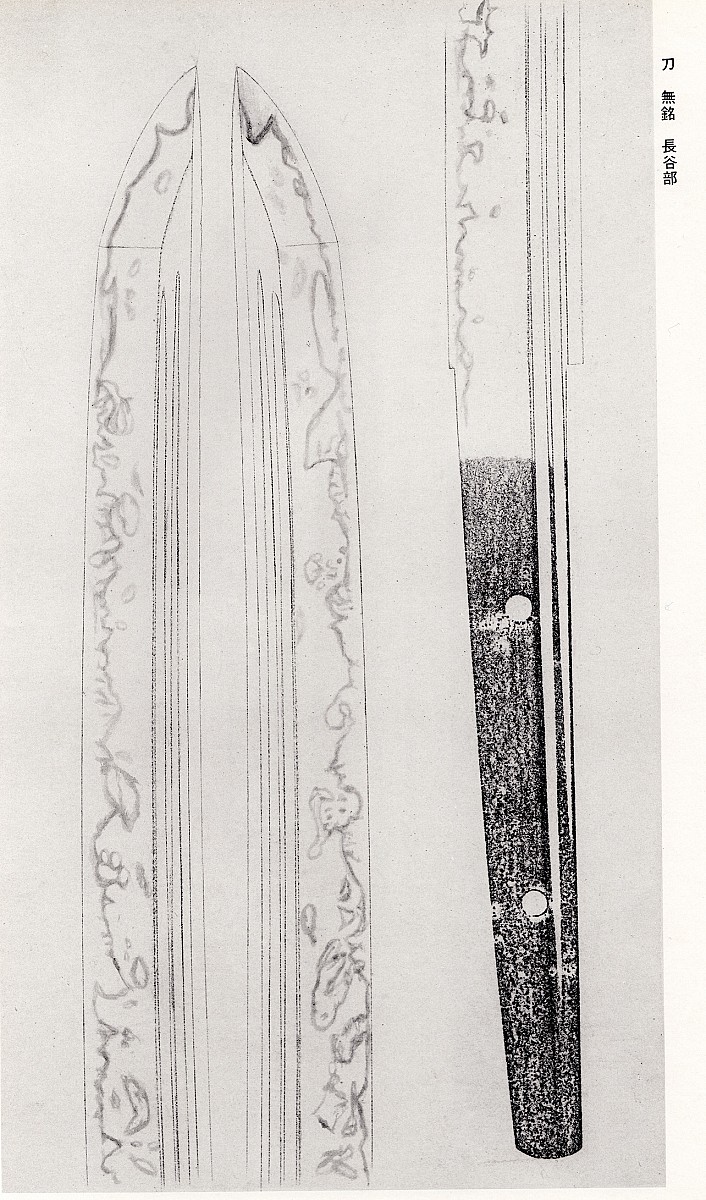

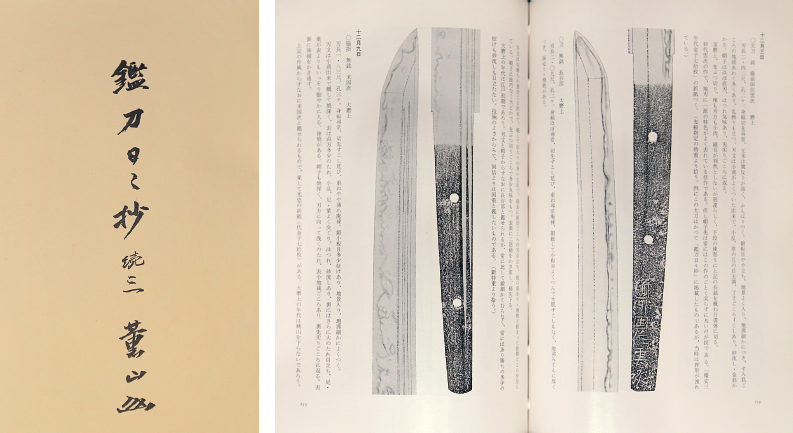

Publications: NBTHK Jūyō Tōken Nado Zufu, Volume 8; NBTHK Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken Nado Zufu, Volume 7; English version of Tōken Bijutsu Journal No. 9 (summer 1981)—the first major double-page spread; the Japanese version of Tōken Bijutsu Journal; Kantō Hibi Shō by Dr. Honma, Appendix No. 3, 1990, pp. 254–255.

The sword was exhibited in the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art, in the NBTHK Sword Museum, in the Chidō Museum, in the Komatsu Museum, and in the Kaga Museum of History and Folklore.

Figure 1: Tōken Bijutsu Journal (Japanese version), Tōken Bijutsu Journal (English version), Kantō Hibi Shō.

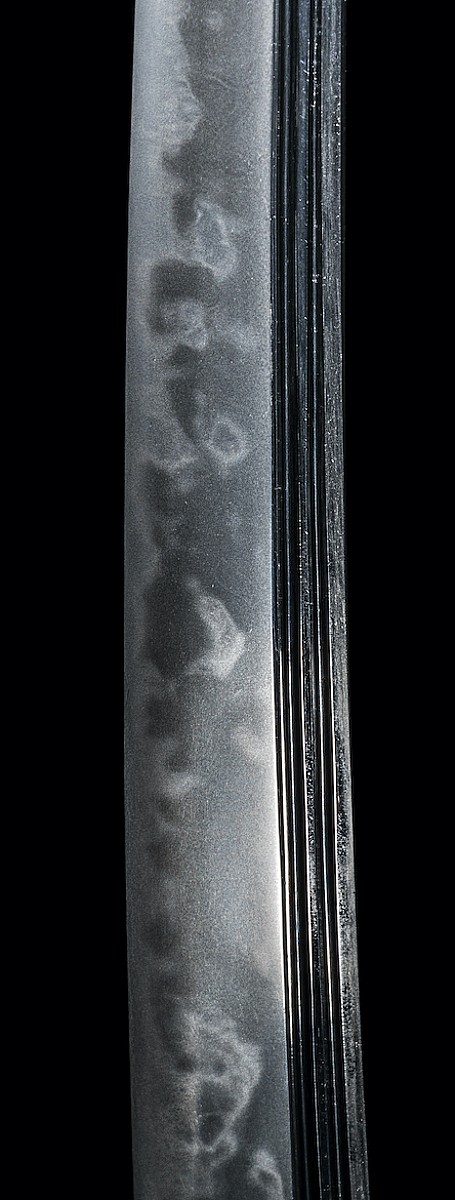

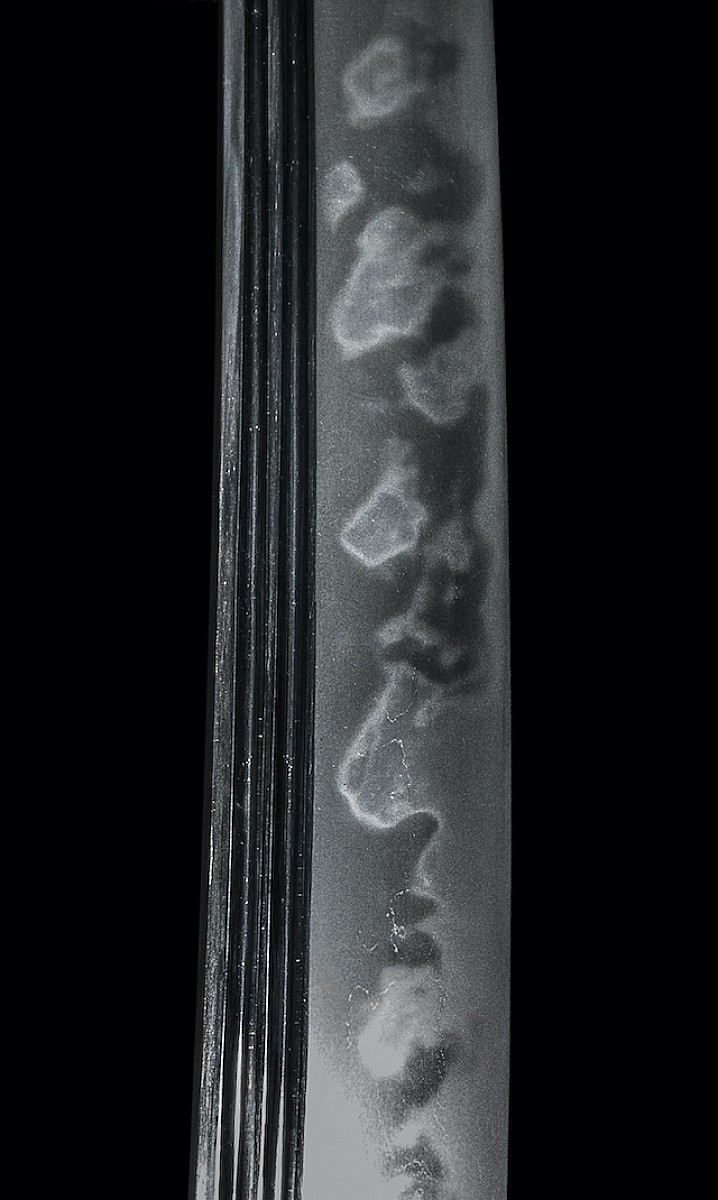

The sword presented here is a very important example of the Hasebe School’s forging art. It is very rare to see the full use of hitatsura on a long sword from this time period. Yet we can find many examples of smiths using hitatsura on both short and long swords in later periods, such as in the Muromachi period. However, after widely spreading across many schools and provinces, this forging practice became less refined over time and its formerly excellent craftsmanship diminished in quality. Later generations used this complicated method in their work with less and less success. For us, it is more valuable to see an example of the early and classic use of hitatsura on a long sword, combining the highest-quality forging and perfect understanding of all the processes of metal hardening. The old masters who founded this style obviously worked with supreme skill, and it is unfortunate that over time their knowledge and practices were partly or completely lost. There are few examples of full hitatsura on a long sword: to date, only 12 extant works (Jūyō and higher). Neither Hiromitsu nor Akihiro left any surviving examples of full hitatsura on long swords, although a few had partial hitatsura. Only the Hasebe School produced examples of long swords with full hitatsura tempering along the entire blade’s length. Therefore, the sword “Tokubetsu Jūyō Hasebe” provides a very rare opportunity for us to understand the skill level of the old masters who founded the hitatsura techniques.

<.....> In terms of production quality, it can be noted that currently, there are only 11 long swords with Tokubetsu Jūyō status and above attributed collectively to Kunishige, Kuninobu, and Hasebe. The sword presented here stands out even from this small number, due to the full application of hitatsura and unusually excellent preservation, by any standards. The chief curator of the National Museum in Tōkyō believes that the “Heshikiri Hasebe” and the Tokubetsu Jūyō Hasebe are the best, most impressive works from the Hasebe School.

It should be noted that long Hasebe swords generally have a shorter nagasa, compared to swords from other schools. They were initially created relatively short, and, in consequence, when they were shortened, this resulted in an even smaller size. In all long swords attributed to the Hasebe School, the nagasa averages 68.74 cm in length (compared to the nagasa of Sadamune’s long swords, averaging a length of 69.90 cm).

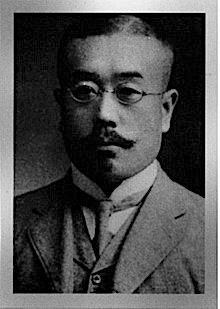

Figure 2. Katsurada Fujirō.

The sword described here also provides a rare opportunity to trace its history during the last two hundred years. The very fact of that someone saved the documents, together with the sword, is a unique and very unusual occurrence. The provenance is as follows. During the Edo period, the sword was in the collection of the Maeda clan, which was the most powerful clan of Japan in the days of Tokugawa Ieyasu. After that, the sword was donated by the Maeda clan to a world-renowned medical scientist, Katsurada Fujirō (桂田富士郎, June 7, 1867–April 5, 1946), who came from a samurai family in Kaga. Katsurada Fujirō was a pioneer in researching certain species of parasites; he was also the president of the Japanese Society of Pathologists (since 1918) and the first Japanese citizen to be awarded the title “Honorary Member of the Royal Society of Medicine of England” in 1929. Most likely, the sword was presented to him by Maeda Toshinari (前田利為, June 5, 1885–September 5, 1942), after they became acquainted in London in 1913. There, Maeda was trained at the Military Academy, and at the same time Katsurada was a representative of the Japanese Medical Association. After that, the sword became a family heirloom of the Katsurada family.

Figure 3. Maeda Toshinari.

Later, the sword passed on to Araya Kumakichi, who was the founder and president of Araya Industrial (established in 1903 in Ōsaka) and Daidō Kogyō (founded in 1919 in the city of Kaga) corporations.

In the postwar years, the owner of the sword was Kuroda Masashige. It was he who submitted an application for the sword to get Jūyō shinsa status in 1962. On his behalf, the sword was exhibited in July 1971 at the Ishikawa Prefectural Art Museum, as evidenced by the letter of gratitude written to the owner of the sword from the museum director Kuwata Yoshio (桑田良夫). Later, Miyabo Kenji became the owner of the sword and, in 1980, presented an application for this sword to get Tokubetsu Jūyō shinsa status. On his behalf, the sword was displayed in exhibitions at the NBTHK Sword Museum, the Chidō Museum, and the Komatsu Museum.

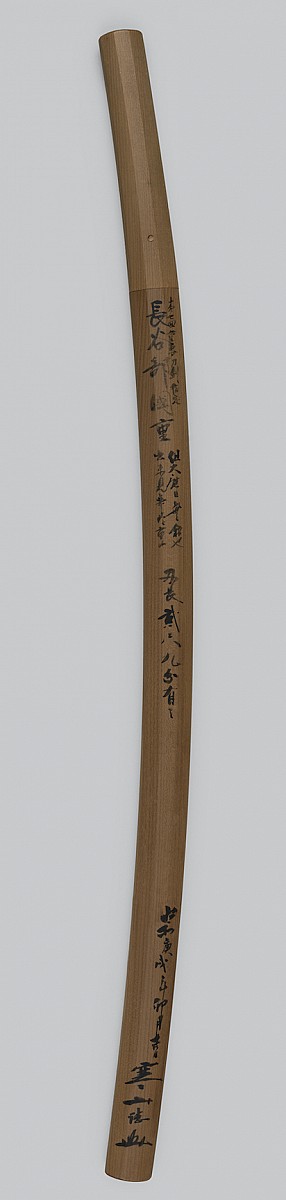

In April 1970, Kanzan Satō, at the request of Miyabo Kenji, made an assessment of the sword, attributing it to “Hasebe Kunishige.” It has a corresponding sayagaki on the old shirasaya of the sword. This sayagaki can be roughly translated as: “Hasebe, received the Jūyō Tōken status at shinsa No. 8; it was shortened and, as a result, lost the signature; the work is of outstanding quality; nagasa of 2 shaku, 9 bu, on the happy day of April 1970, Kanzan, Kaō.”

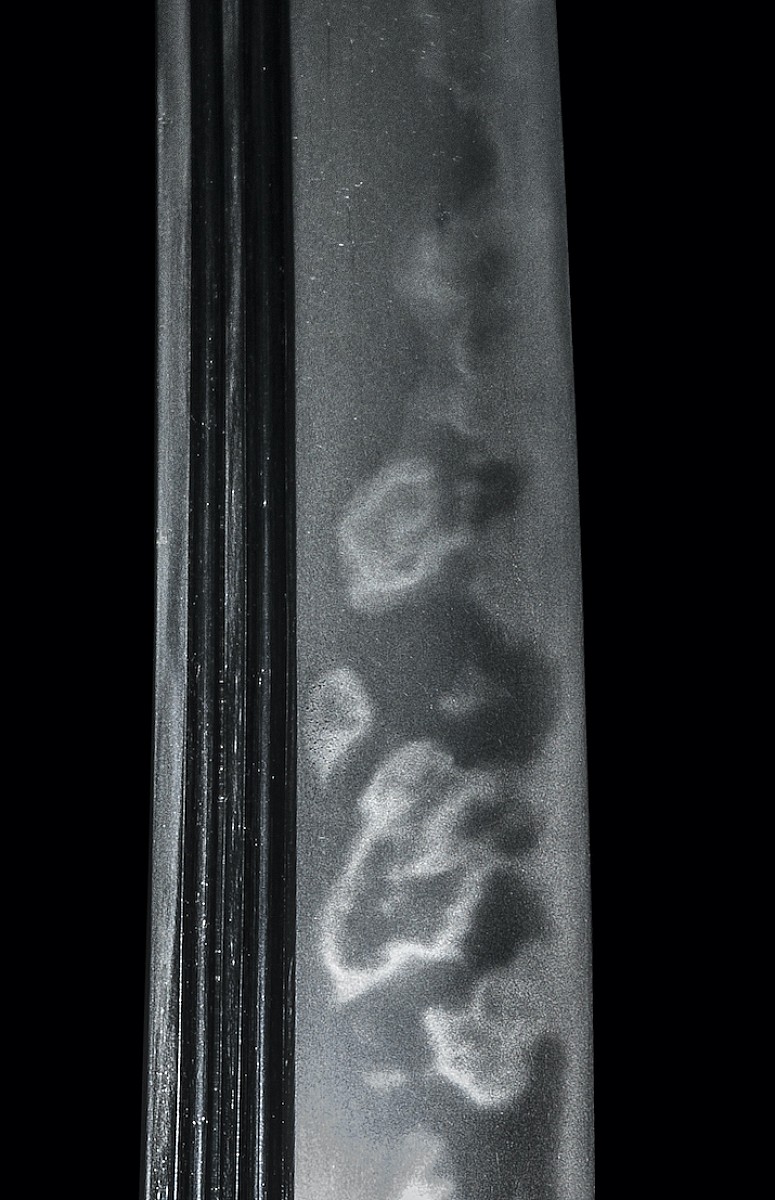

In the early 1980s, this sword was examined by Dr. Honma Junji, and the results of this study were published in Supplement No. 3, Kantō Hibi Shō (鑑刀日々抄), pp. 254–255. Dr. Honma wrote: “Nagasa 63.5 cm, two mekugi-ana, a normal mihaba, kissaki slightly elongated, a normal kasane, iori mune, kitae—very dense ko-itame with no large structures of ō-hada in general, abundant ji-nie, yubashiri, and tobiyaki. The hamon is nioi-deki, but mixed with ko-nie and manifests itself as an ō-midare with large waves. On the haki-omote side, there are karimata elements along the ha with the yubashiri and the tobiyaki in the ji area, which can be called the components of hitatsura. The bōshi is made in a very elegant and natural manner with rounded elements and wavier to the tip. On the both sides, there are futasuji-hi, ending with kaki-nagashi in the tang and starting with hisaki-sagaru. It seems that the ō-suriage was made at the beginning of the Edo period. Cumulatively, the hamon and the bōshi undoubtedly attribute this sword as Hasebe’s, but its kitae is of a higher quality and more homogeneous than usual and there is no tendency to masame and sunagashi, as is often seen in works attributed as the “Hasebe School.” Thus, taking into account the skill level of the smith shown in this work, the sword should not be attributed to Kuninobu, but to Kunishige. The sword has just got the status of Tokubetsu Jūyō.”

Figure 4: Hasebe katana oshigata. Kantō Hibi Shō, Supplement No. 3, p. 254.

After that, until recently, the sword’s owner was Murakami Shintarō, and it was he who displayed the sword in an exhibition at the Museum of History and Folklore of Kaga City dedicated to great countrymen (including Katsurada Fujirō). The exhibition was held from June 26 to August 29, 2004. The key facts of its provenance were established by the museum staff on the basis of studying the family chronicles of the Katsurada clan in preparation for the exhibition. All the collected facts were accurately presented in the corresponding exhibition brochure, preserved with the sword.

(excerpt from Chapter 11, pp. 276-293, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces )

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov