Kunimitsu (国光), Shōan (正安, 1299-1302), Sagami, first name „Shintōgo“ (新藤五), some sources list him also with the name „Shintōtarō“ (新藤太郎), according to transmission the son or student of Awataguchi Kunimitsu (粟田口国光), some say he was the son of Awataguchi Kunitsuna (国綱), because of his family name „Hasebe“ some assume that he had a certain relationship to the Hasebe school. Tokaido (東海道), saijō-saku.

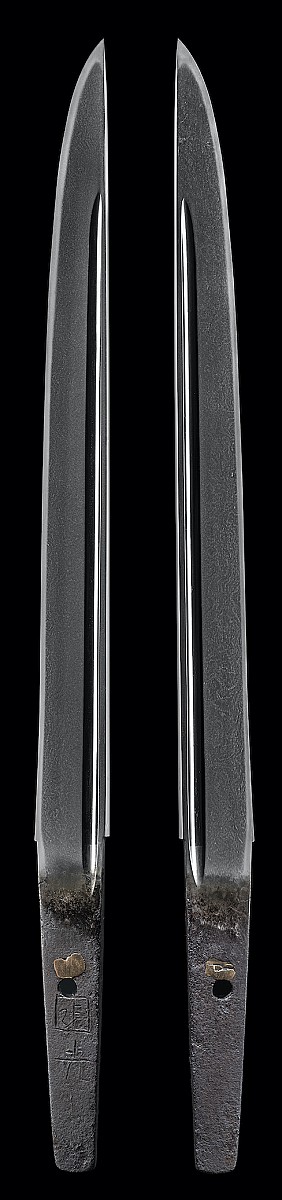

Jūyō Token Shintōgo Kunimitsu Tantō: nagasa: 24.3 сm; motohaba: 2.2 сm; nakago nagasa: 10.3 сm; nakago sori: none.

Designated as Jūyō Token at the 29th jūyō-shinsa held on the 8th of December 1982.

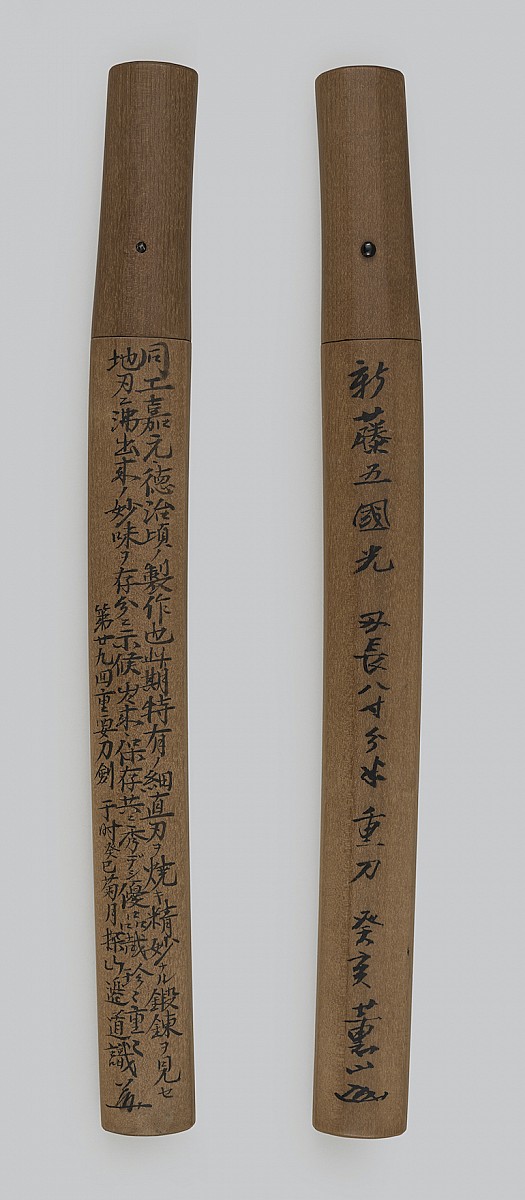

Nakago ubu, mei “Kuni Mitsu,” origami Hon’ami Kōjō (本阿弥光常), dated in the fifth year of Genroku (元禄, 1692), value: 10 mai, a family heirloom of Iyo Hisamatsu (伊予久松) – Matsudaira (松平) from Matsuyama (松山); the shirasaya has two sayagaki: on the omote side, it was made by Kunzan (D. Honma Junji) in 1983; on the ura side, by Tanzan (Tanobe Michihiro) in September 2013 (the translations are given at the end of the chapter); polishing was done by Fujishiro Matsuo (Ningen Kokuhō); one of the former owners was Yashizawa Kazuyuki (芦沢一幸).

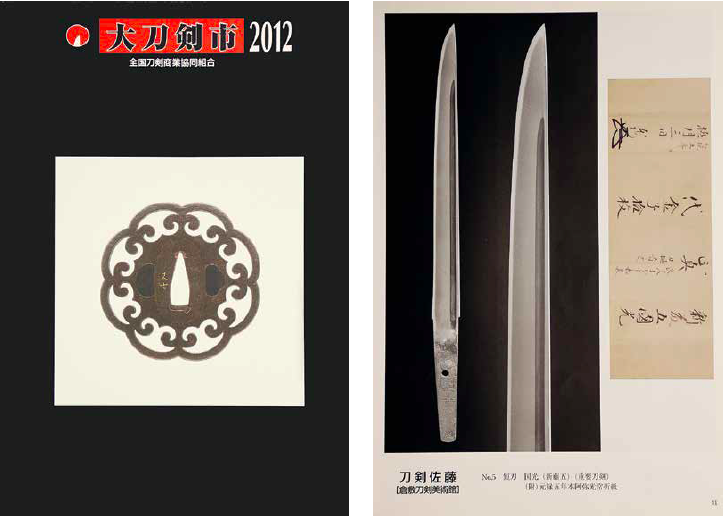

Publications: NBTHK, Jūyō Tōken Nado Zufu, Volume 29, Dai Tōken Ichi Сatalogue of 2012, p. 11.

Figure 1: “Dai Tōken Ichi” Catalogue".

The tantō represented here is Shintōgo Kunimitsu’s typical work and a vivid confirmation of the smith’s skills, as well as of his reputation as the most accomplished master of creating tantō (on a par with Awataguchi Yoshimitsu). Kunimitsu’s perfectionism, manifesting in the tantō sugata he made and unequivocally characterizing him, has rendered this shape of tantō “classical.” Many experts believe that in terms of style, the sugata of Kunimitsu’s swords looks more elegant, “light,” and impetuous, compared with Awataguchi Yoshimitsu’s work. Using this tantō as an example, we can verify the fairness of this conclusion. Surely, preferences with regard to sugata may be different, but no one can remain indifferent to the extraordinary elegance the master imbued in the gradual narrowing of the blade in the direction of the kissaki, which was harmoniously attuned with the size and proportions of the tantō itself.

Although this sword is not dated, the period of its manufacture, according to Tanobe sensei, can be determined as sometime between 1303 and 1308. The extremely skilled workmanship is evidence of the work of a mature master at the peak of his creativity. Only in works by great masters can we see such a clear line of suguha hamon and ji-hada, rare in terms of beauty and quality and made in the best traditions of the Awataguchi School. The presence of katana-hi emphasizes the elegance of this tantō. This type of horimono is a rarity in Shintōgo’s works.

An old origami Hon’ami Kōjō has survived, dated 1692. Hon’ami Kōjō (1643–1710), who was given the name Saburōbei (三郎兵衛) at birth, was a representative of the 12th generation of the main descendants of Hon’ami, who was the eldest son of Hon’ami Kōtatsu and the father of Hon’ami Kōchu. This is a very old origami, and, unfortunately, we have very few Hon’ami-origami of this age. The translation of these documents is of special historical interest, both as an example of an expert appraisal in old Hon’ami traditions, and as a document confirming that this sword was stored as a family legacy of the Iyo Hisamatsu clan. The figure shows two variants of Hon’ami Kōjō’s personal stamp (Nihontō no Kantei to Kenma, 1975, p. 190).

12th generation: Kōjō (光常), Tadamasu (忠益), “the 8th month of the 1667 year”, “the 2nd month, the year of the Dog, of the 1670 year”

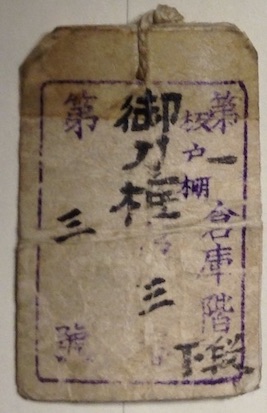

Envelope: 別二。新藤五國光折紙。十枚。別極?両。“Hisamatsu family heirloom.” “Separate [certificate] ten gold pieces [for a] Shintōgo Kunimitsu origami. Separate ?attribution? Ryō”

Origami: “Shintōgo Kunimitsu, authentic, nagasa 8 sun, katana-hi on the omote and ura, value 10 mai. Genroku 5th, Hon’ami Kōjō + Kaō.” [Note that the assessment is made in accordance with the quantitative criteria set forth in the Kokon Meizukushi Taizen: 10 mai for Shintōgo’s works. For this reason, it looks slightly too low, but it is typical for early origami, and only later did appraisers stop relying on these numerical criteria].

Sayagaki (omote): 新藤五國光。刃長八寸分違。重刀。癸亥。薫山 “Shintōgo Kunimitsu, blade length exactly 8 sun, designated as Jūyō-tōken, Year of the Boar (1983), Kunzan (Honma Junji).”

Sayagaki (ura): 同工嘉元徳治頃。製作也此期特有。細直刃ヲ焼キ精妙ナル鍛錬ヲ見セ地刃ニ沸出来。妙味ヲ存分ニ示候出来・保存共ニ秀デシ優品哉。珍々重々第廿九回重要刀剣。于時癸巳菊月探山邉道識。 “Work of the smith from around Kagen (嘉元, 1303–1306) and Tokuji (徳治, 1306–1308). It shows the typical hoso-suguha of that time, it is fine and excellently forged, and the jiba is in nie-deki, which results in a very attractive and fascinating blade. Both the deki and its condition are excellent. It is a great and very precious masterwork. Designated as Jūyō-tōken in the course of the 29th Jūyō-shinsa. Written by Tanzan (Tanobe Michihiro) in the ninth month of the Year of the Snake (2013).”

Regarding the master’s signature on this work, we can say that all of the above features, mandatory for Shintōgo Kunimitsu’s signature, appear on the sword’s tang. This signature includes an absolutely vertical dividing line in the “Kuni” kanji; a calligraphic style of writing the “crown” in the “Mitsu” kanji, with a strictly parallel left stroke of the “crown,” and the tilting leg of the “Mitsu” kanji ends with a rising upstroke. Thus, when studying this sword, we have a unique opportunity to see in detail, in a “vivid” example, all of these features of the master’s signature, which are mentioned in both old and new sources. With this masterpiece, we also have another copy of the master’s genuine signature, which can be valuable reference material for scholars of the Sagami School’s creative output.

Tag: Stack No 1, lower drawer, Sword frame No 3, No 3.

According to the tōrokushō, this sword was registered on December 23, 1955, which is quite an early date. This early period refers to the registration date of items from the daimyō collection, which at that time were subject to priority registration. Unfortunately, no documents have survived to confirm that at the time of registration, this sword was still owned by descendants of the Iyo Hisamatsu clan. However, the very early date that the tōrokushō was issued lets us assume that this was quite possible. Only a few surviving swords were the family legacy of this clan. Only 8 other swords, in addition to the above, have documented confirmation of their origin with the Iyo clan.

(excerpt from Chapter 3, pp. 42-57, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces )

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov