Hiromitsu (廣光), 1st gen., Bunna (文和, 1352-1356), Sagami – „Sagami no Kuni-jū Hiromitsu“ (相模国住廣光), „Hiromitsu“ (廣光), „Sagami no Kuni-jūnin Hiromitsu“ (相模国住人廣光), first name „Kurōjirō“ (九郎二郎), according to transmission the son of Sōshū Sadamune (貞宗), but some see him as student or son of Masamune (正宗). Tokaido (東海道), saijō-saku.

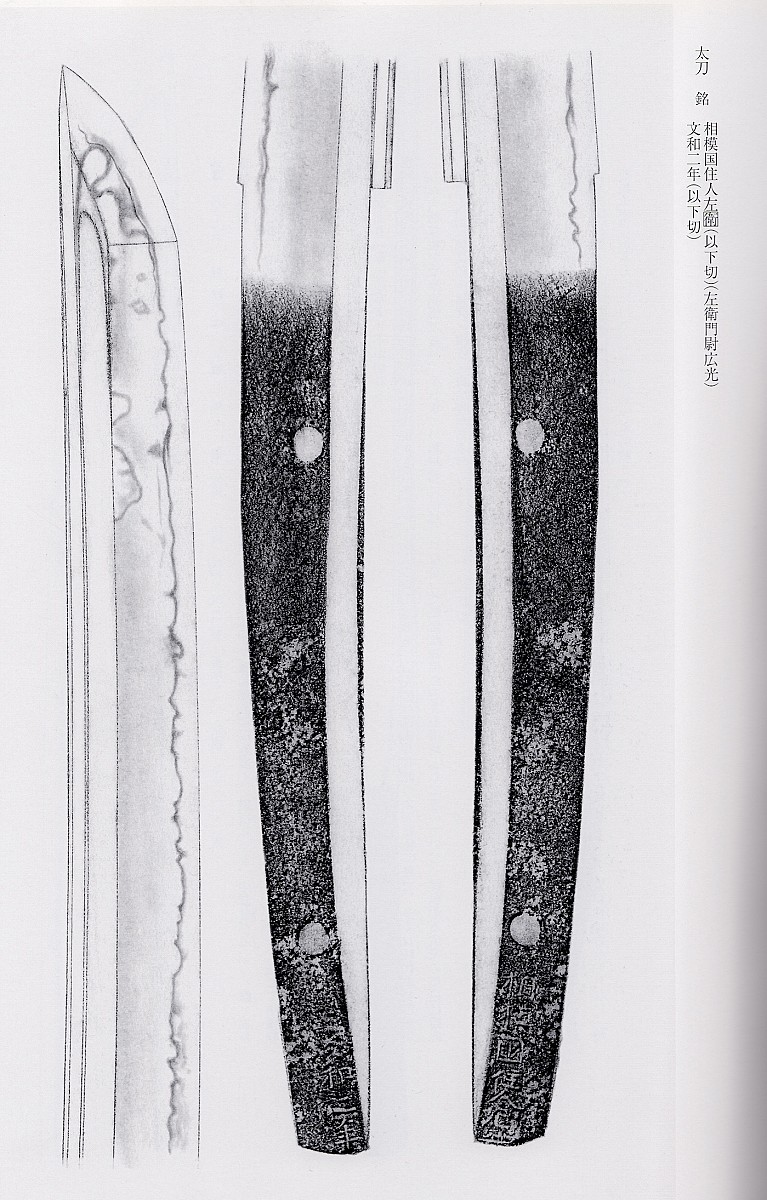

Jūyō Bijutsuhin; Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken Hiromitsu Tachi: nagasa: 75.1 сm; sori: 3.05 сm; motohaba: 3.1 сm; sakihaba: 2.4 cm; kissaki nagasa: 4.2 cm; nakago nagasa: 22.4 сm; nakago sori: 0.2 cm. Signature: 相模国住人左衛 (inhabitant of Sagami Sa E . . .), date: 文和二年 (the second year of the Bunna era, 1353). Family heirloom of the Echizen Matsudaira (越前松平) clan, daimyō of the Echizen Fukui (福井藩) fief, No. 60 in the list of family heirlooms. The sword was stored in the collection of Matsudaira Masano (the governor of Kumamoto Province, ambassador of Japan to the United States during World War I) and Kawabata Masanobu (Kumamoto Province) until the beginning of the World War II. The sword was polished by Fujishiro Okisato (藤代興里) under the supervision of Fujishiro Matsuo (藤代松雄, Ningen Kokuhō—Living National Treasure, 1914–2004) in 2003. The sword was found in early 2003 by Ralph Bell in the United States, after more than 55 years when no information was available about its location.

Designated as Jūyō Bijutsuhin on the 6th of September 1939, and Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken at the 18th tokubetsu-jūyō-shinsa held on the 12th of March 2004.

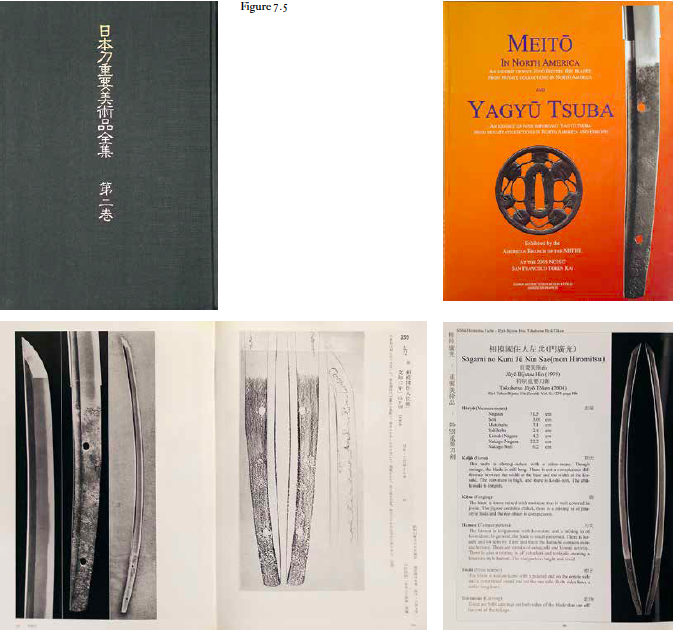

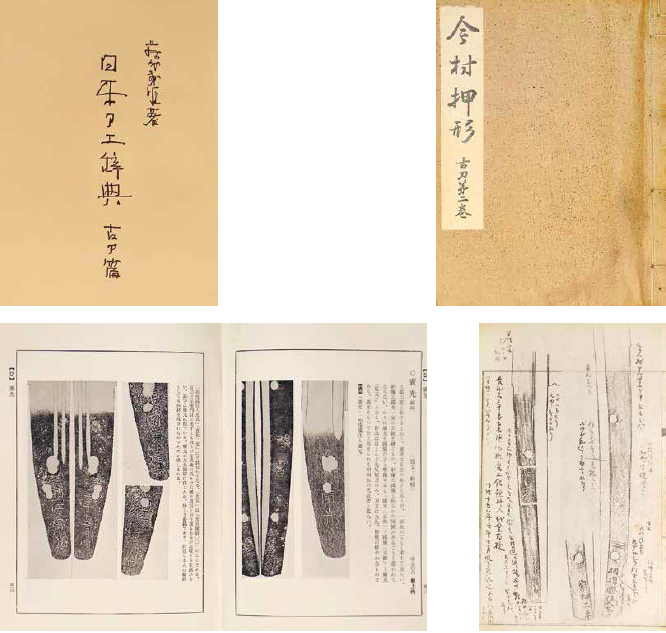

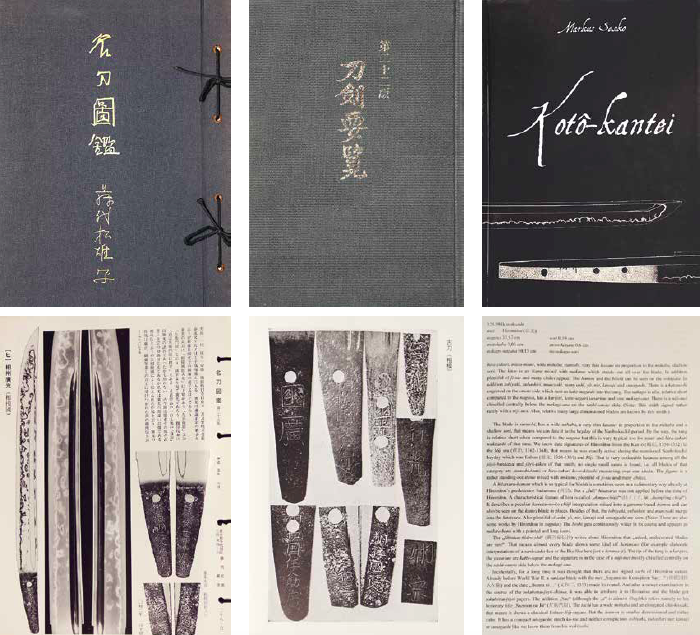

Publications: NBTHK Jūyō Tōken Nado Zufu, Volume 49; NBTHK Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken Nado Zufu, Volume 18; Nihontō Jūyō Bijutsuhin Zenshū (日本刀 全集), Volume 2, p. 186; Meitō in North America (NCJSC, 2005), on the cover and pp. 37–39; Nihon Tōkō Jiten by Fujishiro Yoshio (Kotō-hen, 1987), pp. 512–513; Imamura Oshigata (Volume 2, Ōsaka, 1927), p. 36/2; Meitō Zukan by Fujishiro Matsuo, Volume 28, p. 6; Tōken Yoran by Iimura, 1980, p. 417; described in Kotō-kantei by Markus Sesko, 2012, p. 295.

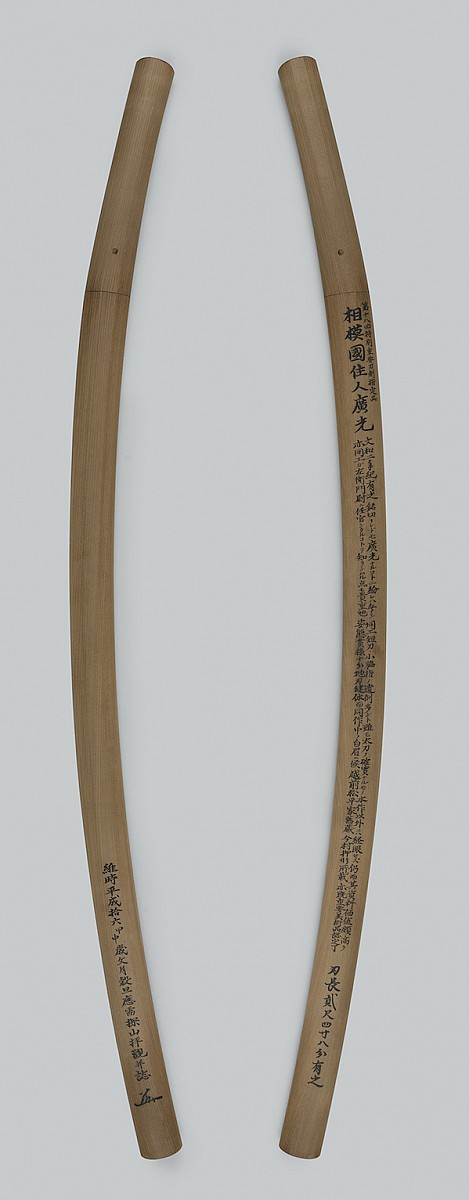

A shirasaya for the sword was manufactured in 2003 by Takayama Kazuyuki (高山一之; see The Craft of the Japanese Sword, 2008, pp. 144–164), the sayagaki was made by Tanobe Michihiro in 2004 (the translation of this sayagaki is given at the Chapter 7, pp. 162-205, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces book), and a special inspection and valuation was made in the United States by Theodore W. Tenold (www.legacyswords.com) in 2012.

The story of Dr. Walter A. Compton returning the Kokuhō sword by Saburō Kunimune to Japan from the United States in 1953 is widely known, especially since Compton did not demand any compensation for his extremely generous act. However, another similar event actually took place not so long ago, also in the United States. In early 2003,Ralph Bell, an American collector, bought a sword, a Jūyō Bijutsuhin Hiromitsu tachi, that was considered to have been lost since the end of the WWII. Bell bought it in an ordinary, unspecialized antique store, where someone had taken the sword after it was stored for several decades among the possessions of a former military officer of the U.S. occupation forces. In the list of “Missing Swords During the Occupation” by Albert Yamanaka (Albert Yamanaka’s Nihontō Newsletter, Volume 3, pp. 239–252, San Francisco, 1994–2004), this sword was mentioned under number 24. According to available records, “on October 10, 1945, it was delivered by its owner to the police station of Kiyama in the town of Mifune (御船), Kumamoto Prefecture. Then, the sword was handed over to one of the following three US Commanders in the prefecture of Kumamoto: Regimental Commander Colonel MacFarland, or Kumamoto Prefectural US Military Government Lieut. Colonel Rink, or Administrative Officer Major Sobel.”

This discovery is so important in the study of the Sagami School that during the San Francisco Tōken Kai in 2005, a separate exhibition was held: Meitō in North America. At this exhibition, five swords were presented having the status of Jūyō Bijutsuhin and stored outside Japan in private collections in North America, including this sword by Hiromitsu. At the end of this exhibition, the American Branch of NBTHK issued a special commemorative brochure for this event. A separate article dedicated to the sword by Hiromitsu was written for this edition by Robert Benson, who is rightfully considered the leading expert in the United States in the field of Japanese swords. Below, you can find the full text of this article and the translation of setsumei quoted after Meitō in North America and Yagyū Tsuba (Allegra Print & Imaging, Reno, NV 2006, pp. 36–41):

SETSUMEI Tokubetsu Jūyō:

"Hiromitsu and Akihiro were two artists who followed Sadamune and are representatives of the Sōshū tradition. Hiromitsu’s tachi with indisputable signatures are extremely rare. The majority of his extant works are the large-sized tantō and short wakizashi that are characteristic of the time. Further, a Sōshū work with this uniquely tempered hitatsura has not been seen previously. Dated works of Hiromitsu can be found from Kan’ō (1350), Bunna (1352), Enbun (1356), Kōan (1361), and Jōji (1362–1368).

Although the signature on this work has been cut off after “Sagami no Kuni Jū Nin Sae,” from the engraving style of the characters, the construction, and the appearance of the ji-ha, it has been possible to attribute this blade to Hiromitsu. Other extant works on which a recognized official title has been inscribed do not exist; however, we are able to read half of the Saemonnojō characters. From the point of view of research, this is very remarkable.

The style of workmanship differs slightly from the magnificent appearance of the ko-wakizashi yubashiri and tobiyaki are few, and the muneyaki is not conspicuous. The hitatsura tempering being rather quiet, gives the blade the appearance of a rather older style. The blade is wide and long, and the chū-kissaki is extended, giving the blade an imposing feeling of bold construction. There is rich hira-niku, and both the ji and the ha are strikingly healthy. Hiromitsu’s tachi with indisputable signatures are almost never seen, and the existence of this blade is extremely valuable. As an example of a work on which the smith engraved his official title, the value of this blade as a source of research information is immeasurable.

This is one of the swords that was handed down in the Matsudaira family of Echizen. It has been published in the Imamura Oshigata".

Figure 1. Imamura Chōga.

COMMENTS BY ROBERT BENSON:

"This sword is one of the most important swords from the Soshu school that is outside Japan. Its importance can not be overemphasized. It had been one of the family heirlooms of the Echizen Matsudaira family. The Echizen Matsudaira was founded by Tokugawa Hideyasu, the second son of Tokugawa Ieyasu, and his descendants formed the eight branches of the Echizen Matsudaira.

In Meiji 28 (1895), Matsudaira Masano of the Echizen Matsudaira family known as Fukui Matsudaira, brought this daito to Imamura Chōga for appraisal. The attribution of this long tachi had been a matter of conjecture for centuries. It had been thought to be Sadamune because of the “Sagami no Kuni Ju Nin” part of the inscription.

In the Imamura Oshigata it is noted that the sword was submitted by the Chiji of Kumamoto prefecture for evaluation. Chiji means the governor, and this is the same Matsudaira Masano who was the ambassador to the United Sates during The First World War. The notes further mention that Imamura san had not reached a decision about the sword at that time. The next time, this sword was published in the Nihon Tōkō Jiten, Kotō Hen, by Fujishiro Yoshio. There it was listed as Hiromitsu, though it mentioned the question about Sadamune, seemed to dismiss it.

The sword was submitted by Mr. Kawabata from Kumamoto for elevation to Jūyō Bijutsu Hin, which was granted on Shōwa 14, 9th month, sixth day (September 6, 1939). We can find it listed at the end of the section on Sōshū in the eight volume set of Nihontō Jūyō Bijutsuhin Zenshū. It is not listed as Hiromitsu, but just as “Sagami no Kuni Jū Nin Sae” with the date of Bunna 2 (1353). However, in the description it does say that it looks like Hiromitsu.

What is actually the proving point that the blade is Hiromitsu, is that the kanji are exactly like numerous intact signatures on sunnobi tantō.

This sword disappeared from Japan at the end of The Second World War and went unrecognized until purchased in California by an American collector in early 2003. Recognizing that this was a work of great significance, he had it taken to the NBTHK research department where it was declared the quintessential find of the century. They insisted that it be submitted to the Tokubetsu Jūyō Token shinsa where it passed easily in 2004.

In Homma Sensei’s Sōshū Den Meisaku Shū, there are two Hiromitsu daito, a gakumei daito and the famous o-suriage, Jūyō Bijutsu Hin with dragon horimono that had belonged to Date Masamune. This is only the third known daitō by Hiromitsu, and the only one with most of the signature intact. There are over twenty Jūyō Tōken and Tokubetsu Jūyō Tōken blades, but no signed daito until this piece was brought to light. It is an extremely important find. In Japan, it has been stated that had this still been in Japan in 1950, when all the Kokuhō were downgraded to Bunkazai, and new Kokuhō were selected from Jūyō Bijutsu Hin and Bunkazai ranks, this piece would have likely been promoted to Bunkazai. We are lucky to have such an important piece with Tokubetsu Jūyō and Jūyō Bijutsu Hin rank in this country".

Figure 2. Robert Benson.

Despite the unequivocal opinions uttered by Robert Benson and NBTHK experts, the sword is still a greater mystery than it seems at first sight. This mystery is comparable to the story of its loss and discovery. In this regard, let us dwell on those points that represent this mystery, especially since they are a vivid example of how difficult it is to say something definite and precise about events that happened almost seven centuries ago. (detailed investigation regarding this tachi could be found at pp.184-195 of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces book).

<.....> Yet regardless of the outcome of research in this field, we know one undeniable fact: this sword is not merely the only long sword signed by Sadamune or Hiromitsu. It is, in principle, the only signed and dated long sword of the old Sagami School. Without belittling the role of Shintōgo Kunimitsu, we can classify Yukimitsu, Masamune, Sadamune, Hiromitsu, and Akihiro as representatives of the “pure” Sagami School. However, none of these masters made signed long swords that have survived to our day. Therefore, the uniqueness of this sword cannot be overemphasized. It is simply the only signed and (at the same time) dated long sword of the “old” Sagami School existing in our time.

(excerpt from Chapter 7, pp. 162-205, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces )

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov