Sōshū Sadamune (相州貞宗) had several disciples. Similar to “Masamune no Jittetsu,” experts talk about “Sadamune no Santetsu” (貞宗三哲), which included the following craftsmen: Bizen Motoshige (元重), Yamashiro Nobukuni (信国), and Tajima Hōjōji Kunimitsu (但馬法城寺国光). The Kotō Meizukushi Taizen gives the birth and death dates for only one of Sadamune’s disciples: Hōjōji (1289–1355), which means that he was as much as ten years older than his teacher. In addition, the same source names Shigezane (重真), Motoshige’s elder brother, instead of Nobukuni, as being among Sadamune’s disciples and also adds Akihiro to that circle, thus bringing the total number of Sadamune’s disciples up to four.

Another of Sadamune’s disciples, who should be considered separately from all the others, was Takagi Sadamune (高木貞宗) from Ōmi Province, the native province of Sadamune himself. The reason we should consider him separately is that some sources claim that he was Sadamune’s son, who was personally trained by him and who traveled with him. According to this theory, after the death of his father, the son took Sadamune’s name and started signing his works “Takagi Sadamune.”

The Kotō Meizukushi Taizen contains some very interesting information about him: it says that Takagi Sadamune was born in the Enoki (エノ木) settlement, after which he was sometimes called Enoki Hikoshirō (エノ木彦四郎). He became one of Masamune’s disciples at the age of thirty-five. Furthermore, the same source mentions that his original name was Hiromitsu (弘光) and that he possibly used that name with an antiquated form of the “Hiro” kanji (廣) to sign his works. Another confirmation of that theory can be found in the Kokon Kaji Bikō, which points out that early in life, Takagi Sadamune used to sign his works as Hiromitsu (弘光) and Sukesada (助貞). Clearly, this information helps us consistently and logically explain why, at an early age, Hiromitsu signed his name with two kanji. It is quite possible that the smith using this signature was Takagi Sadamune—in other words, Sadamune’s own son, who used that signature early in his career. After Sadamune’s death, his son started signing his works as Takagi Sadamune, using his father’s name. That also helps explain the wildly different styles between Hiromitsu’s earlier works signed with niji-mei and later ones signed with naga-mei. And most important, it helps explain the completely different quality of deki, which would be possible only if its maker were Takagi Sadamune. While that smith’s deki were less perfect than Sadamune’s, their quality was better than that commonly associated with Hiromitsu’s works.

Regarding Takagi Sadamune’s birth in the Enoki settlement, there are some doubts, articulated, in particular, in the Tōken no Shin Kenkyū. The source states that actually “Enoki” was a bastardized spelling and pronunciation of the name of a place called Hiraki (平木). That used to be a small settlement near the Hirata (平田) village in Takagi, in the region called Gamō (蒲生), where he really was born. The confusion was due to incorrectly written calligraphy depicting the 平 kanji, which was sometimes written as エ, and as a result, the theory states, Takagi Sadamune’s actual name was Hiraki Hikoshirō, not Enoki Hikoshirō.

Among Takagi Sadamune’s disciples, Kanro Toshinaga (甘呂俊長) is widely believed to be the most distinguished; he was an exceptional master of the yari (“lance”). Once he put the most fascinating signature on one of his swords: “student of Takagi Sadamune from Ōmi, inhabitant of Echigo—Tenkurō Toshinaga—made.” Another of Takagi Sadamune’s disciples was Takahiro (高弘), whose son Sukenaga (助長) later went on to become the founder of the Ishidō School.

Figure 1: Kotō Meizukushi Taizen, vol. 2, p. 15/1.

It is widely believed that only tantō made by Takagi Sadamune survived to our times; furthermore, even ancient sources preserved oshigata only for short swords. As an example, there is a signed tantō (Jūyō Bijutsuhin No. 242, Nihontō Jūyō Bijutsuhin Zenshū, Volume 2, p. 192) attributed to Takagi Sadamune, which used to be the property of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The signature on that blade reads Gōshū Takagi-jū Sadamune (江州高木住貞宗). Hon’ami Kōtoku attributed that tantō to Sadamune (the corresponding oshigata was published and described in the Kōtoku Katana Ezu Shūsei). The oshigata from another signed tantō was included in the Kōzan Oshigata. However, in the opinion of the NBTHK board of experts, Takagi Sadamune also forged long swords. The modern consensus about attributing swords made by that smith is as follows: there are in total 34 known swords made by Takagi Sadamune: 32 with Jūyō status (6 katana, 20 ko-wakizashi, and 6 tantō); 1 with Tokubetsu Jūyō status (a katana); and 1 with Jūyō Bijutsuhin status (a tantō)—the blade we discussed earlier.

According to widespread opinion, Takagi Sadamune’s craftsmanship was a level below that of his mentor, and he could never match Sadamune when it comes to the quality of the jigane. According to the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen, swords made by Takagi Sadamune may be dated to the Enbun era (延文, 1356–1361), although in old manuscripts, some pictures of sword tangs have dates coinciding with the period of Sōshū Sadamune’s career. An example would be an oshigata dated with the 2nd month of the 2nd year of the Ryakuō era (暦応, 1339), as well as an oshigata included in the Tsuchiya Oshigata (Volume 1, p. 128): “Gōshū Takagijūnin Sadamune,” dated the 2nd year of the Kareki era (嘉暦, 1327).

There is also a theory concerning the phenomenon of Takagi Sadamune, whose works greatly resemble those of his teacher. This theory proposes that Takagi Sadamune’s works were, in fact, made by Sadamune himself in the twilight of his career. Some sources mention that as his career was coming to an end (in the period from 1345 to 1352), Sadamune was invited to Ōmi Province by the protector (shugo—守護) Rokkaku Ujiyori (六角氏頼, 1326–1370), to make a copy of one of his own most widely known swords, the “Tsunagiri” (綱切り). That sword was once owned by the protector’s famous ancestor Sasaki Takatsuna (佐々木高綱, 1160–1214). In 1184, Takatsuna cut a rope (tsuna) with that sword, which was where the blade got its name. Obviously, Sadamune succeeded in that task, because the Nihontō Daihayakka Jiten (日本刀大百科事典) mentions that the Rokkaku clan owned a meitō named “Tsunagiri Sadamune.” Sadamune never returned to Sagami after that, staying in Takagi for the rest of his life, and to affirm that fact, he allegedly changed his signature to Takagi Sadamune. To confirm the version of the story that says Sadamune returned to Takagi, one can read the entry on page 20 of the manuscript Ōseki Shō. According to this entry, “Sadamune returned to Takagi and married a woman from Takagi.”

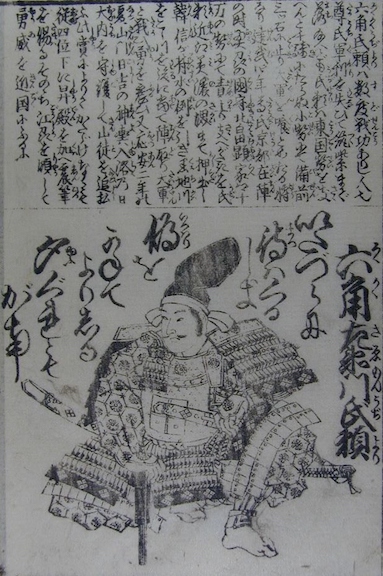

Figure 2. Rokkaku Ujiyori.

Currently, these two theories can be neither confirmed nor dismissed, because there are no authentic signatures attributed to Sadamune on any swords. Very few of his works have survived, and there is even a theory asserting that similar to his mentor Masamune, Sadamune never signed any of his swords, and all the signatures inscribed on oshigata were added later. However, we have to admit that the second theory of “the same smith” has far fewer arguments going for it. If we are to agree with it, then the dates widely accepted for Sadamune’s life and career should be reconsidered and considerably extended.

(excerpt from Chapter 6, pp. 132-159, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces )

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov