One of Shintōgo's most famous disciples was Sōshū Yukimitsu (相州行光). Together with Shintōgo Kunihiro, they were the eldest among the four most illustrious of Kunimitsu’s disciples, the others being Masamune and Norishige. Collaboration and joint training contributed to their mutual influence on each other in the process of forming their own styles. However, it is reasonable to assume that they all worked in the style of their teacher at the beginning of their careers.

According to Fujishiro Yoshio, the very small number of Yukimitsu’s signed swords that survived can be explained by the fact that he was one of the disciples who made swords in the exact style of Shintōgo and put Shintōgo’s signature on them, rather than his own. This was time-consuming work, and Yukimitsu had virtually no time to spend on his own creative endeavors.

According to Fujishiro san, Yukimitsu’s genealogical line was that of Shintōgo’s disciple. This branch was not the central one in Kamakura during his teacher’s life. Besides, Shintōgo was a much more famous master, a leading smith and the head of the school, so his creative vision and his works were more important at that time. For this reason, his son Kunihiro and his senior disciple Yukimitsu were involved as Shintōgo’s assistants and disciples for quite a long time, having almost no opportunities to use their own creativity.

Figure 1. Fujishiro Yoshio.

We can consider these assumptions more like a legend, especially since Yukimitsu created his own style so rapidly and successfully that it was considered the classic style of the Sagami School. That is, despite the fact that such great masters of smithing as Masamune and Norishige worked with him at about the same time, it was Yukimitsu’s style that people regarded as the classic one.

At birth, Yukimitsu was given the name Tōsaburō (藤三郎), and some sources tell us that he was not only a disciple, but also a son of Shintōgo. Other sources, however, say he was most likely a son of Bungo Yukihira (豊後行平), who later moved to Kamakura from his native province. According to some preserved records, there were two smiths with the name Yukihira: one of them worked during the Genkyū era (元久, 1204–1206) and the second one during the Shōō era (正応, 1288–1293). It can be noted that both of these periods of activity are somewhat inconsistent with Yukimitsu’s years of life (presumably, 1247–1330), unless the first Yukihira was much older when he gave birth to a son.

In general, there is no unambiguous way to decide who was Yukimitsu’s father, although the years of Shintōgo’s creative output are most consistent with Yukimitsu’s years. As for the formation of his smith’s name, he could have adopted the first kanji of his name from Yukihira and could have adopted the second kanji from Kunimitsu. Unfortunately, it is not possible to compare the writing of the 行 kanji by Yukimitsu with that of the second, later Yukihira, due to the lack of signature samples. Nevertheless, if we compare it with that of the early period of Bungo Yukihira (YUK53, Genkyū, 元久, 1204–1206), whose works have survived, we can note that the writing of the 行 kanji is slightly different.

In the signature by Bungo Yukihira, two upper oblique strokes of the left radical are almost vertical, short, and very close to each other. With the 光 Yukimitsu’s kanji, on the contrary, we can see a clear similarity with Shintōgo’s writing. These masters wrote the “Mitsu” kanji in a very similar manner, which is especially easy to demonstrate because there are enough extant samples of these two masters’ signatures.

Therefore, many experts agree with the opinion that Yukimitsu was a son of Bungo Yukihira. After moving to Kamakura, Yukimitsu became a disciple and then an adopted son of Shintōgo Kunimitsu. When forming his smith’s name, he took the first kanji from his father’s name, Yukihira, and the second one from the name of his teacher Kunimitsu.

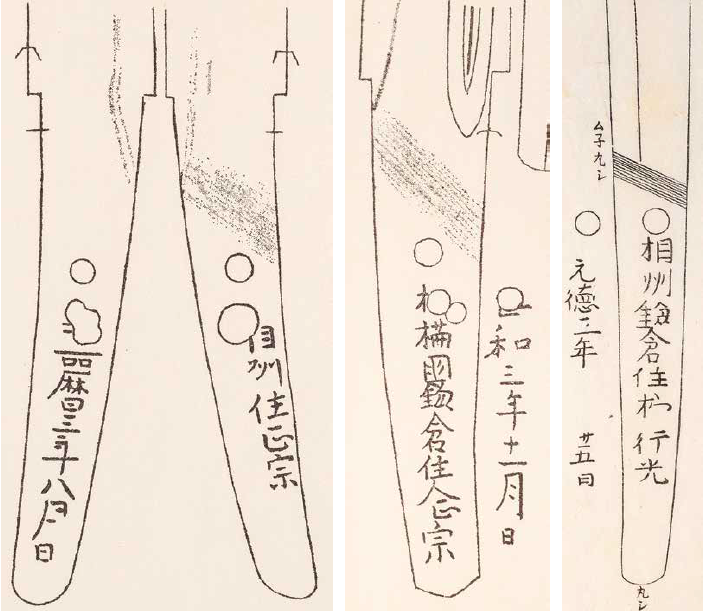

Figure 2. Kokon Meizukushi Taizen, Volume 5, pp. 16/2, 17/1.

The lack of a conclusive opinion can be noted in the question as to whether Yukimitsu was the father of Masamune. In old sources such as the Kanchi-in Bon Mei Zukushi (観智院本銘尽, published in 1423, on the basis of records made from 1299 to 1316), the Shinsatsu Ōrai (新札往来, 1367), and the Katsuragawa Jizō Ki (桂川地蔵記, 1416) describing the line of the Sagami School, Masamune and Yukimitsu are considered junior disciples of Shintōgo Kunimitsu. That is, Yukimitsu’s and Masamune’s kinship being that of father and son has never been mentioned. In these books, they are placed in one row, within the genealogical line descending from Shintōgo.

Ise Sadachika (伊勢貞親, 1417–1473) was the first to write that Masamune was a son of Yukimitsu in his records, which were first published in 1488. Another source that contains a direct mention of their relationship as father and son is the Ōseki Shō (往昔抄, 1519). Subsequently, all credible sources, such as those compiled by Takeya Ri’an (竹屋理安, 1589), the Shinkan Hiden Shō (新刊秘伝抄, 1573–1592), and the Funki Ron (粉寄論, 1596–1615), contain information about the relationship of Yukimitsu and Masamune as father and son. Yet it is necessary to note one interesting detail: Takeya Ri’an, one of the leading experts of the Momoyama period, mentioned Masamune as a son of Yukimitsu and a disciple of Saburō Kunimune in his records dating back to 1579 and to 1589 (Masamune was born in 1264, whereas Kunimune presumably died in 1270). If we accept this version, this slightly shifts the years of Masamune’s life and makes him almost a contemporary of Shintōgo. Otherwise, we should assume the existence of several masters who bore the name Masamune (see details in the next chapter).

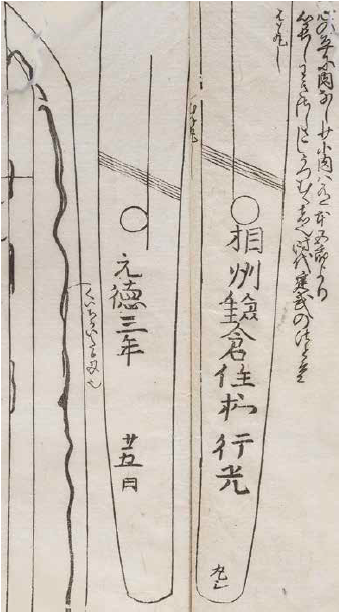

Figure 3. Oshigata Yukimitsu. Kōzan Oshigata, Volume 坤, p. 32/2; Umetada Meikan, pp. 29/2, 31/1.

<.....>Thus, even though we study numerous old sources, it is impossible to obtain ultimate clarity and documented confirmation of the true nature of the Sagami School founder’s kinship. However, we can say that most likely Yukimitsu was the actual son and a disciple of Bungo Yukihira, and, later, he became an adopted son of Shintōgo Kunimitsu. Concerning Masamune, he was the actual son of Yukimitsu and a disciple of Shintōgo and probably a disciple of Saburō Kunimune at an initial stage of his study.

At the same time, it is worth noting a bit of strangeness in the formation of Masamune’s smith name. Contrary to traditions usually followed by a disciple, he took neither the “Kuni” kanji nor the“Mitsu” kanji from the name “Shintōgo Kunimitsu.” In addition, he took no kanji from Yukimitsu’s name to form his own smith’s name. In old sources, we cannot find any other alternative names associated with either Masamune’s birth or his education, which could be the sources he used to form his smith name. Therefore, the only assumption we can make about its formation is that Masamune really was a disciple of Saburō Kunimune for a while. It was the kanji of Kunimune’s smith name that Masamune took to form later his own name. It is possible that Shintōgo himself played a role in this. If we believe certain assumptions, while remaining the head of Kamakura smiths, Shintōgo considered himself more a representative of the Kamakura-Awataguchi line and positioned himself more as a smith of the Awataguchi School. Conversely, Masamune, having taken the “Mune” kanji from Kunimune’s name, stressed that he himself inherited the line and the trend created in Kamakura by Saburō Kunimune’s works.

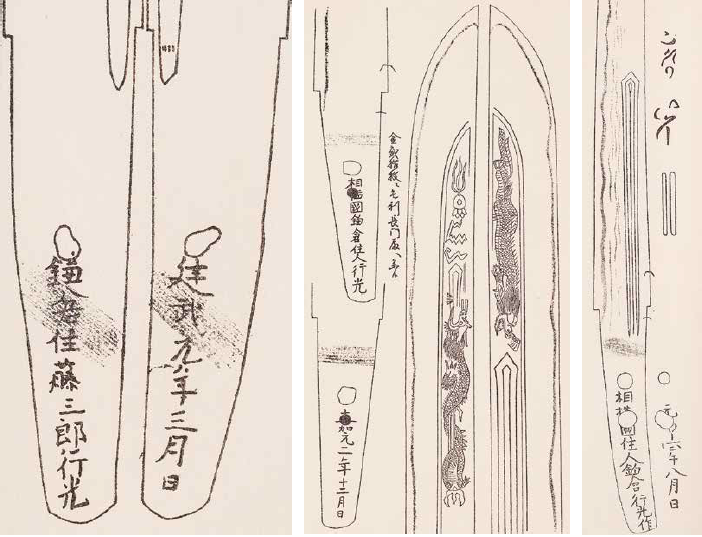

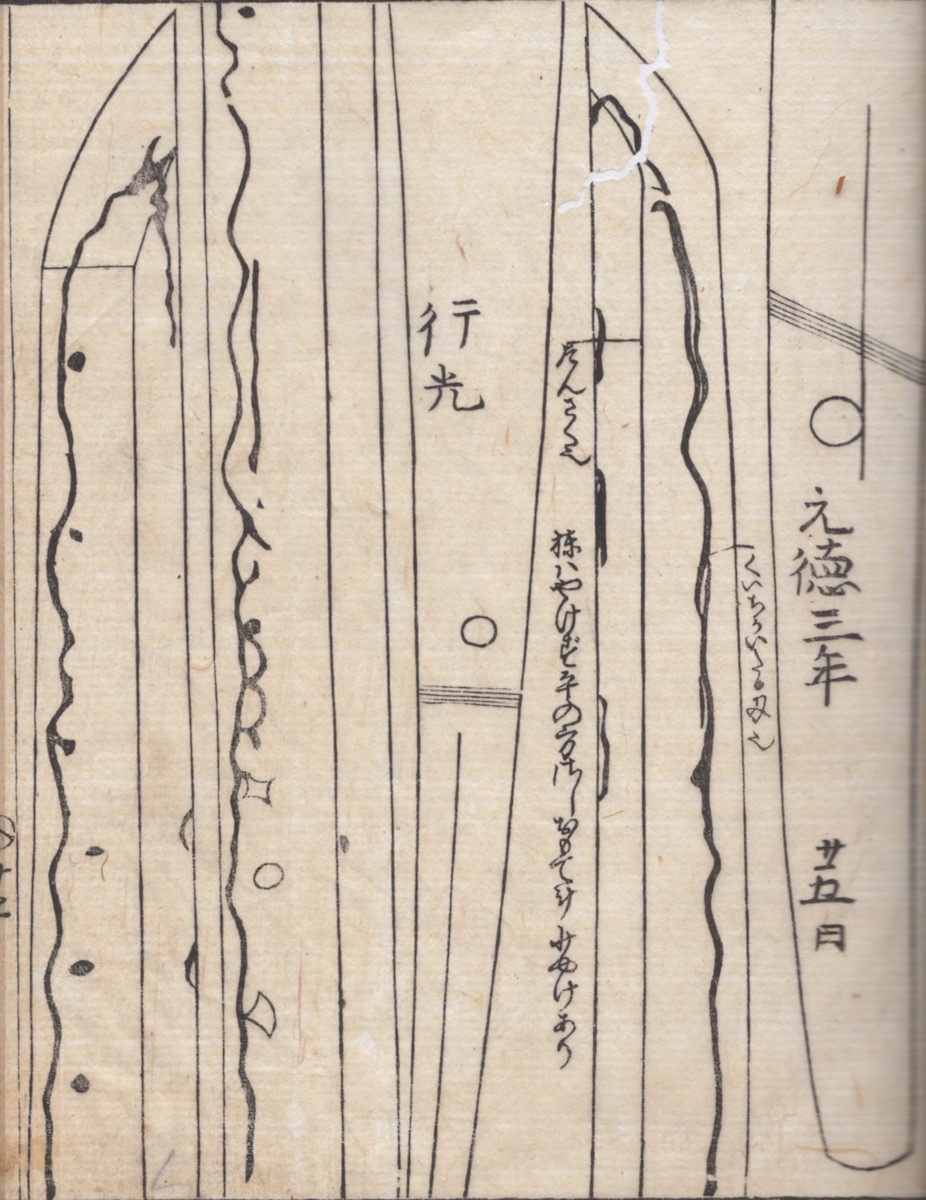

Figure 4. Oshigata Masamune. Umetada Meikan, pp. 33/1, 36/2. Oshigata tachi Yukimitsu: Kotō Meizukushi Taizen, Volume 7, p. 15/2.

A very interesting legend about the relationship between Yukimitsu and Masamune is described in Honchō Kōshi Den (本朝孝子伝), chronicles of famous family scandals and incidents that were published in 1686, based on oral folklore. This legend is described by Markus Sesko in his book Masamune. His Work, His Fame and His Legacy (2014). It tells us that Yukimitsu was born in Bizen Province and was a handsome young man. Soon after he moved to Kamakura, he married Oaki (お秋), a daughter of Morikawa Umanosuke (森川右馬允). Her father was a wealthy resident of Kamakura, who later paid for Yukimitsu’s journey to Kyōto to improve his skills in learning techniques of renowned masters of the Awataguchi School. There, Yukimitsu made great strides and was honored to forge a sword for the emperor himself. His son, Shintarō, was lazy and inept, so Yukimitsu had to think about who would later continue his work. At the same time, a boy named Gōrō, the son of an artisan, came to his forge and begged Yukimitsu to become his teacher, and Yukimitsu finally agreed to do so. The master became very attached to his talented pupil. Three years later, Gōrō told Yukimitsu that in fact, he was the son of a woman from an aristocratic family in Kyōto. His mother died soon after his birth, leaving him a tantō, which, according to her, had been made by a smith who was his father. Yukimitsu recognized this tantō as his own work, and, with tears in his eyes, he recognized the boy Gōrō as his actual son. Thus, this beautiful legend provides us with another version explaining that Masamune was probably Yukimitsu’s son through an extramarital affair. <.....>

The works by Yukimitsu had the following main features:

Sugata: A classic tachi-sugata, whose beauty is accentuated by a shallow toriizori and often by a slightly elongated kissaki. The sori is quite shallow, as mentioned, which is characteristic of all the works by Yukimitsu. The mihaba is wide; all long swords are ō-suriage up to the nagasa size of about 70 centimeters. Sometimes, we can find long swords with an ikubi kissaki (猪首鋒). They feature a more elegant style, as compared to those that have an elongated kissaki; the latter, however, look strong and powerful. The tantō have an average size, about 26–27 centimeters, with a narrow mihaba, and a mitsu-mune with a wide top face.

Jitetsu: An excellent quality bluish-black steel with the characteristic brilliance. Ko-itame mixed with mokume. Somewhere, there are signs of ō-hada; a high activity of ji-nie and the presence of chikei and yubashiri. Usually, the tantō has a denser and cleaner hada, whereas the play of its elements is manifested more in the area of fukura.

Hamon: The katana and the tantō usually feature high variability. Somewhere, we can see suguba, komidare, ō-midare, and notare, as well as their various combinations; the nioiguchi may be wide or narrow. There is a wide yakiba, a high concentration of ashi, and a lot of nie, which comes from the habuchi and enters inside the ha. In the area of the ha, there are kinsuji and inazuma. The ha is whitish with a blue hue. The tantō shows a beautiful color of nie, as well as yubashiri in the area of the fukura; it may also feature a hitatsura, but most of them are hardened in a hiro-suguha.

Bōshi: A fine, small-size pattern of midare-komi, often ending either with yakizume (焼詰め—“without kaeri”) or kaen (火焔—“a candle flame”), or with manifestations of nie-kuzure. The activity and brightness of nie are higher in the area of the bōshi. Tantō usually have ko-maru with a small kaeri.

Horimono: Bō-hi and futasuji-hi are the most common; sometimes, we can see suken, shin no kurikara, and reliefs in a hitsu.

Nakago: Signed works that have survived to our time can be found only among tantō signed in the niji-mei style. Tachi have a somewhat roundish nakagomune. The nakago ends in a type of kurijiri and kengyō. In tantō, it has the shape of furisode (振袖), tanagobara (たなご腹), and funagata (舟形); yasurime in the type of kiri or sujikai.

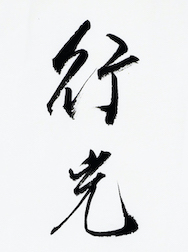

Mei: The most typical is a signature niji-mei. In this case, the first kanji on the katana was located above the mekugi-ana, whereas the second kanji was below it. In the case of a tantō, the entire signature was located below the mekugi-ana. Old oshigata provide examples of the niji-mei signature.

Figure 5. Yukimitsu's elements of activity layout. Kokon Meizukushi Taizen, vol. 5, p. 17/1.

(excerpt from Chapter 4, pp. 60-105, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces )

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov