When Masamune, Norishige and Yukimitsu completed the top achievements of the Sōshū tradition, the style of sword making that came out of their forge in Kamakura swept through Japan. Smiths from other provinces came to train in Kamakura according to old books and then took what they learned back to their home province. Shizu Kaneuji is said to come from the Tegai (手掻) School in Yamato, moved to Kamakura to study under Masamune, then later moved to Mino and became the founder of the Mino tradition. Samonji is said to have come from Chikuzen to study Sōshū techniques, and there is a sharp difference between the blades of his youth in the traditional Chikuzen style vs. these he learned after being in Kamakura. The Nōami Hon Mei-zukushi (能阿弥本銘尽), compiled by Nōami Shinno (能阿弥真能, 1397–1471) was published in 1483, i.e. about 140 years after the death of Masamune, so this was more recent history for this author than it is for us today.

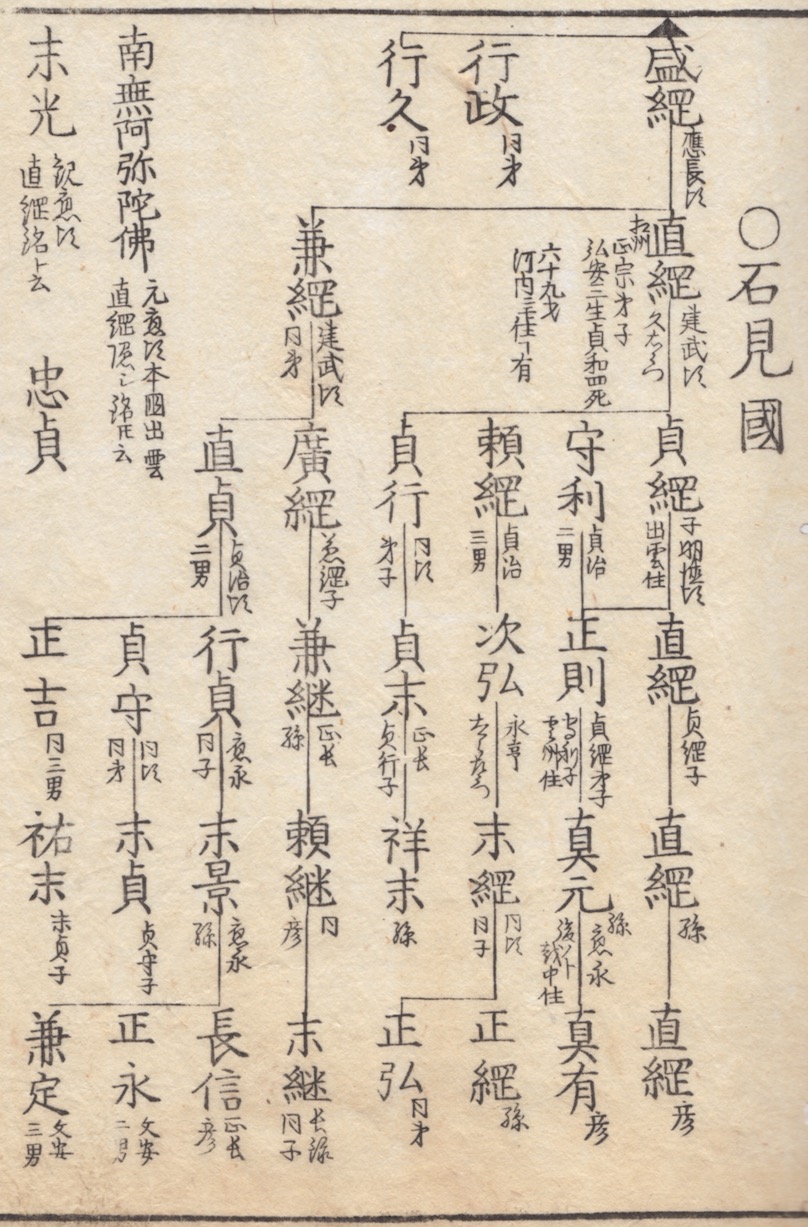

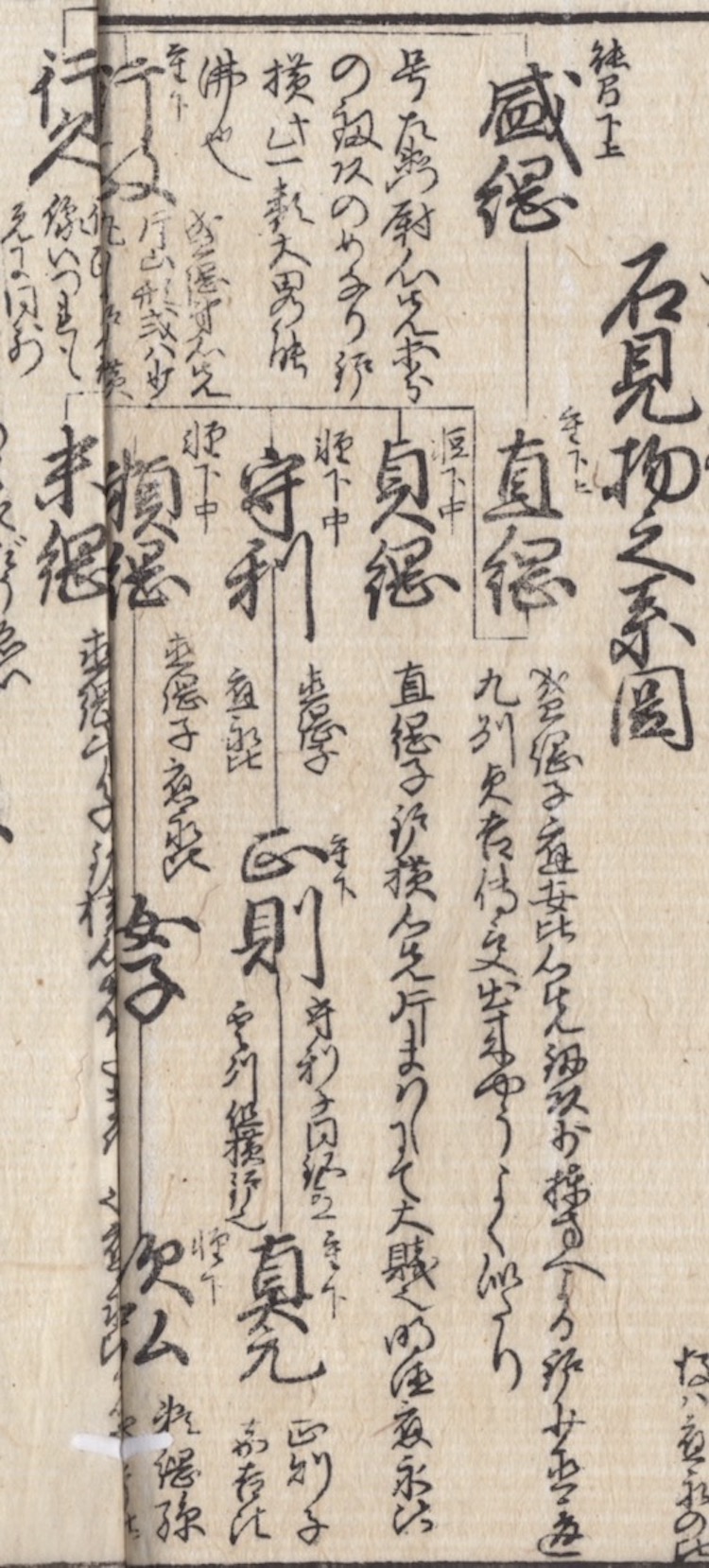

Sekishū Naotsuna (石州直綱) is a line of smiths from Iwami (石見) province and the founder of this line has been included amongst the so-called Masamune no Jittetsu (正宗の十哲) in books since the Muromachi period. According to the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen (古刀銘尽大全), written by Ōgi Iori Sugawara Hirokuni (仰木伊織菅原弘邦), 9 volumes edition 1792, Sekishū Naotsuna was born in the 3rd year of the Kōan era (弘安, 1280) and died in the 4th year of the Jōwa era (貞和, 1348) at the age of 69 (there is an arithmetic error in the source). During the Kenmu era (建武, 1334–1336), he was in his 57th year, and during the Kenmu era (建武, 1334–1336). He came from Iwami province and became a disciple of Masamune. At birth, Naotsuna was given the name Kyūzaemon (久左衛門). There were three generations with the name Naotsuna.

Figure 1. Kotō Meizukushi Taizen, volume 3, p. 4/1.

There is some debate still about the time period or style being right for this to be true, but this is mostly confusion over separating the work of the first and second generations (which was not done in the past, the only sure date anyone ever had was 1376 on a nidai tantō, which would make this too late to be working under Masamune). If we look at all the work of Naotsuna, we will see there are three generations (at least), and that spreads reference examples over some time.

However the Nōami Hon Mei-zukushi, which has frequently been shown to be correct, is the first time he is mentioned in the Jittetsu. This book was published in 1483, and this is just a bit more than a century after Masamune's death which we believe was around 1340. The writer of Nōami Hon was not looking that far into his past in order to write the things he wrote. Nōami Hon as well cited the fact already that Masamune's signed work was few and far between as he was simply the best in Japan.

What we are also told from the old books though is that the shodai worked in Kenmu (建武, 1334-1336) and the nidai in Eiwa (永和, 1375-1379) and the sandai is an Ōei (応永, 1394-1428) period Muromachi smith.

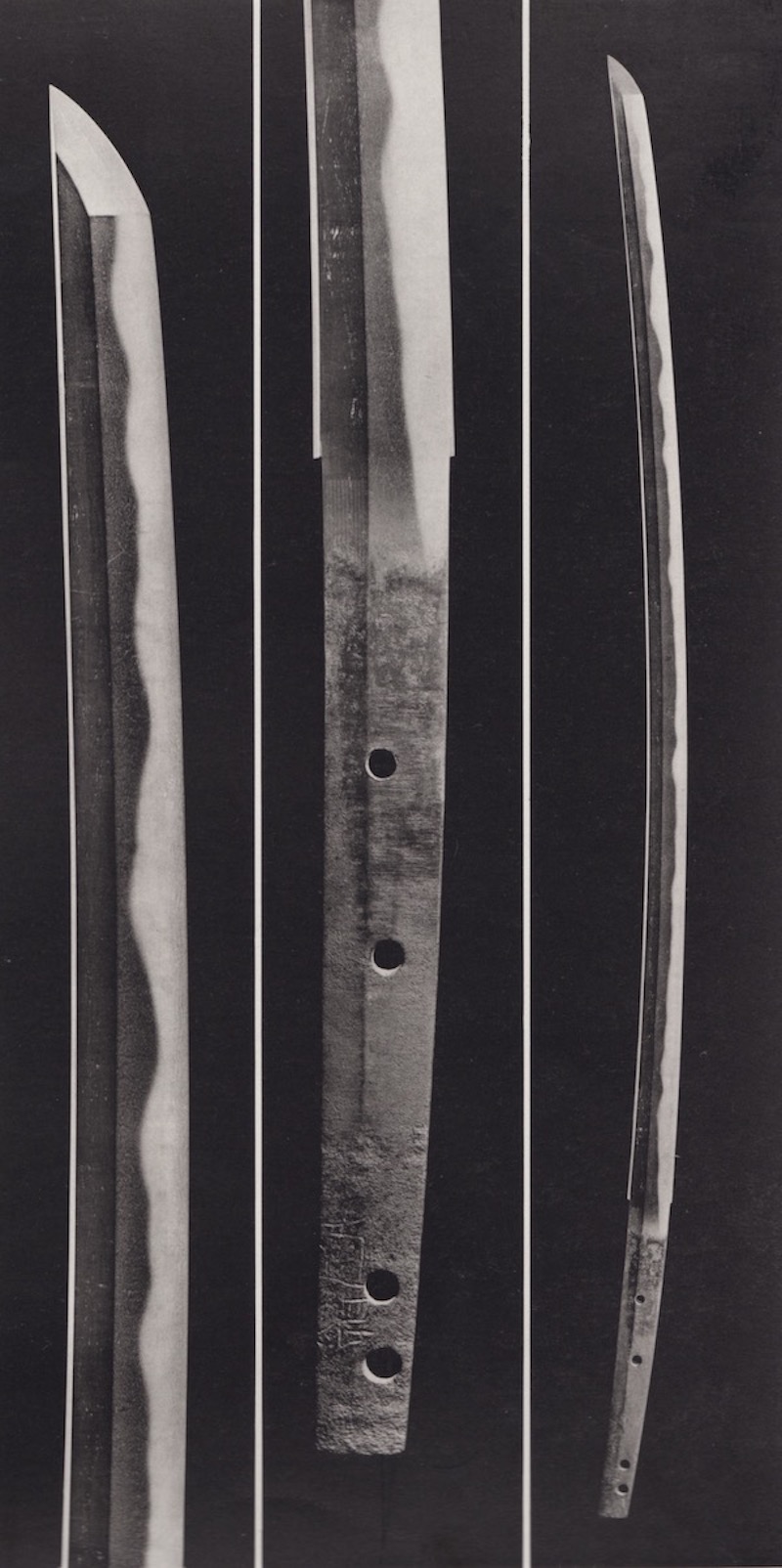

Sekishū Naotsuna — This swordsmith has been considered a pupil of Masamune since the publication of Nōami Hon in Bunmei 15th year (1483). The oldest extant date inscription goes back only as far as Eiwa 2nd year (1376) and the tantō carrying this date is considered a work of the nidai (second generation). There is also a signed example attributed to the shodai, and the mei on this long sword bearing strong Sōshū characteristics was obviously incised by a different hand from the maker's of the aforesaid tantō.

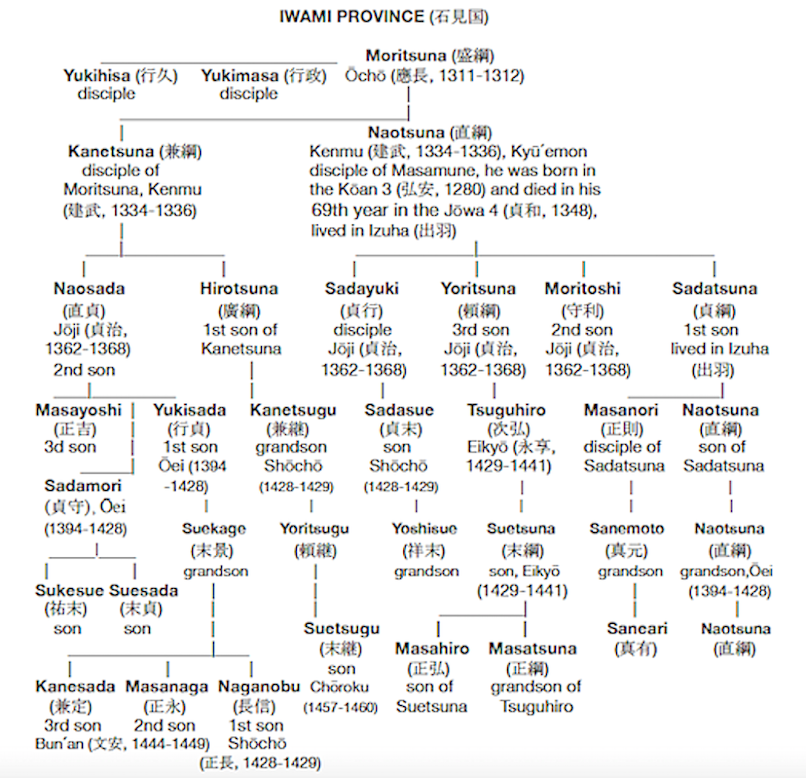

This slim tachi [note: this reference piece to the right], considered to have been made by the shodai, contains outstanding chikei as well as kinsuji and sunagashi, which all clearly indicate the characteristics of the Sōshū product. The Yamato influence, however, can be sensed in the masame mixed in the itame texture as well as in the boshi which is embellished with hakikake and rendered almost in yakizume. Though there still remains the question as to whether Naotsuna actually had a direct connection with Masamune, there seems to be no room for doubting that he did have some kind of contact with the great master of the Sōshū tradition.

— English Token Bijutsu

There is but one other [signed] example slightly older than those considered works of the pupil of Masamune and showing still more obvious ties with Masamune (Tokubetsu Juyo Token).

— English Token Bijutsu

Sekishū Naotsuna has since olden times counted as one of the Masamune no Jittetsu by the Hon’ami family, and his group is thought to have prospered well in Sekishū. At the present time there also seems to be some who have doubts about his being among the Masamune no Jittetsu. I think that from both the standpoint of time and work style, it is justified to believe that he was one.

— Kokura Souemon, Nihonto Koza

Figure 2. Tokubetsu Juyo #4 Naotsuna (shodai). Nihonto Taikan, volum 3, p. 125.

Naotsuna's shodai is considered to have been one of Masamune's ten best students, but the validity of the popular belief has not been firmly established yet. This tachi [the reference piece above] could be work of the shodai. It has the oldest appearance both in the style and the mei, among all the swords bearing the same art name. The mei is clearly different from the one in the tantō dating from Eiwa 2. [...]

His craftsmanship produced a dark iron hue in the ji. Both ji and ha are admirably nie-structured. The hamon is gunome mixed with ko-notare and choji-gokoro variations, creating florid midare accompanying a lot of sunagashi. This almost forms hitatsura-gokoro in places and indicates its having its root in the Sōshū tradition.

— Tanobe Michihiro, English Token Bijutsu

There is as mentioned above only one signed example left to the shodai Naotsuna. There are another 3 Juyo Bijutsuhin, 1 Tokubetsu Juyo and 3 Juyo Token that were made by the 2nd generation Naotsuna and bear signatures.

Figure 3. Juyo Bijutsuhin Naotsuna (nidai). Nihonto Taikan, volume 3, p. 123.

The NBTHK states that the shodai Naotsuna may indeed have worked at the very end of the Kamakura period, which is early enough to have been concurrent with the end of the career of Masamune. The NBTHK generally says that the connection to Masamune still needs more study, but takes pains to note that there were a number of generations of this smith, and one needs to keep this in mind while reading expert opinions from earlier on.

Without a signature the NBTHK tends not to make a strong statement on first vs. second generation construction. My feeling is that most work looks like the 2nd generation, with fewer works looking very strongly Sōshū style like the signed shodai above.

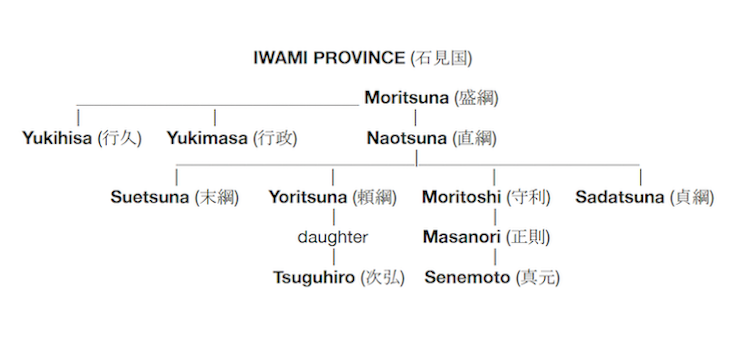

Naotsuna's Iwami School

Fujishiro states that his father was likely Moritsuna of Sekishū (who now has no work left to us but was working in 1312). Fujishiro thinks that Naotsuna's teacher was Sa Sadayoshi rather than being a student of Masamune (Nihon Tōkō Jiten (日本刀工辞典), Fujishiro Yoshio, Fujishiro Matsuo, 1987, volume Kotō, jp. 220). This would make Naotsuna inherit from Sadayoshi and in turn Samonji and then Masamune. This would be an explanation for his learning the Sōshū-den, as Sadayoshi learns from Sa, who is another of the great students of Masamune.

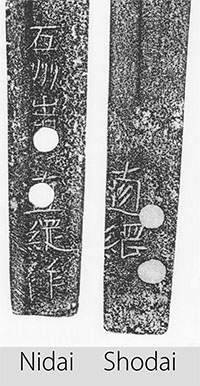

Figure 4. Naotsuna nidai and shodai mei compare.

Darcy Brockbank think Fujishiro's opinion is based on seeing the signed work of the nidai, and in particular the dated item from 1376, as he talks about Ōei era (応永, 1394-1428) primarily. Fujishiro cites the traditional start year of 1324 for Naotsuna (end of the Kamakura period) but did not see the signed tachi used by the NBTHK as evidence for a connection to Masamune. As well, there is not enough time to fit in three generations of Naotsuna if we view the first generation as a student of Sadayoshi.

Since the shodai's style is gunome and choji influenced, it is possible that he inherits through Kamakura Ichimonji Suketsuna. This would place him at the correct time in Kamakura to line up with the old books attestation to his work period in 1326, as Suketsuna is working in the early 1300s. They share half a name, and it explains where he obtained his Soshu style originally as well as making him a contemporary of Masamune and able to take study with him as a co-resident in Kamakura. Note that this is my musing and theory. I think there is always some seed of truth in the old stories if not outright truth, and Naotsuna coming from the Suketsuna line would explain a lot of things.

With another variant of the Sōshū genealogy line, one can get acquainted with Kokon Meizukushi Taizen (古今銘盡大全), 1st edition 1661. Written by Takeya family, 8 volumes edition 1778:

Figure 5. Kokon Meizukushi Taizen, volume 1, p. 20-2.

Following the three generations of Naotsuna are three generations of Sadatsuna (possibly sons and younger brothers). Sadatsuna is also considered a good smith with a Jo-saku rating, and again we encounter a problem deciding between generations. As well as Sadatsuna there is a remarkably large school from Iwami. They include: Kanetsuna, Tsunekane, Naoshige, Naosada, Hirosue, Hirosada, Rinsho, Yoshisue, Kazusada, Sadayuki, Sanetsuna, Suesada and Tsuguhiro (as well as others).

In terms of signing style:

- the shodai signed with „Naotsuna“ (直綱) and „Naotsuna saku“ (直綱作);

- the nidai signed with „Sekishū Izuha-jū Naotsuna“ (石州出羽住直綱), „Sekishū-jū Naotsuna“ (石州出羽住直綱) or „Naotsuna Saku“ (直綱作);

- the sandai signed with „Naotsuna“ (直綱), „Sekishū Izuha Naotsuna saku“ (石州出羽直綱作), „Sekishū Izuha-jū Naotsuna“ (石州出羽住直綱).

Suesada is said to be one of the sons of Naotsuna, and he has left behind a Juyo Bijutsuhin ōdachi with a cutting edge of 167 cm. The Meikan says “Suesada is a son of Iwami Naosada and signs in two characters. There is an extant work with the production date of Ōei 19.” It is believed that any swordsmith needs exceptional forging skill to make ōdachi and then the maker tends to be attributed to one in the earlier period.

— Dr. Honma Junji

Nagayama includes him with Sōden-Bizen makers, though it is hard to exactly conclude a strong Bizen influence in his work. The Naotsuna style is said to look like a mix of Shizu with Samonji, with a black look to the steel. The hamon is usually energetic but in later generations of the Iwami school becomes less wild.

Fujishiro ranks Naotsuna at jōjō-saku (上々作—very high level of skill) rating. His peers in time and school are smiths like Samonji and Shizu. Naotsuna ranks one level below these great grand masters, yet his line is still very highly regarded. Naotsuna works have passed Tokubetsu Juyo, and Juyo Bijutsuhin. Also, Toda Ujiyoshi (a daimyō from Sagami) gave a Naotsuna to the fourth Tokugawa Shōgun Ietsuna as a gift to thank him for a promotion. Kuroda Naokuni (daimyō from Buzen) gave a Naotsuna to the 5th Shōgun Tsunayoshi. Giving a maker at this kind of level, that is, from a daimyō to the shōgun, indicates that the maker had to be held in high regard by all parties involved.

To date, a fairly large number of Naotsuna’s works have survived: 70 swords (only 8 of them are signed), of which 65 are Jūyō, 2 are Tokubetsu Jūyō, 3 are Jūyō Bijutsuhin. Unfortunately, there are very few nidai (2nd generation) works among them: only 2 Jūyō, 1 Tokubetsu Jūyō, and 3 Jūyō Bijutsuhin.

Sukezane’s works have the following distinguishing features:

Sugata: The tachi were shinogi zukuri with a wide mihaba, long with shallow torii sori; the kasane is thin; hira-niku is slight; the chu-kissaki that is elongated, and mune is low. Naotsuna nidai tantō have a wide mihaba and a shallow sori.

Kitae: The itame mixed with mokume tends to nagare; there is a mixture of masame in the vicinity of the shinogi-ji. The color of the steel will tend to be a little dark. There is a tight ko-itame in works of later generations.

Hamon: There are gunome midare mixed with togareba and nie; there are brilliantly clear nie-ashi; plenty of sunagashi and kinsuji, goes into the ji and forms tobiyaki and yubashiri. The nie-deki notare could be found in tantō.

Bōshi: Ko-maru, there is also midare-komi. Those that are deep like ichimai are the most common. There are some in which kaeri is deep. There is a nie-forming hakikake.

Horimono: The bo-hi and futasuji-hi are the most common, in tantō we can see suken, bonji, and gomabashi.

Nakago: The nakago ends in a type of kurijiri, iriyamagata-jiri or the like; yasurime in the type of kiri or sujikai.

Mei: The most typical signatures for shodai are „Naotsuna saku“ and „Naotsuna“; nidai signed also nagamei.

Author: Darcy Brockbank (published on the www.yuhindo.com).

Original content Copyright © 2019 D. Brockbank

Edition and supplements: Dmitry Pechalov.