Hitatsura (皆焼), a special way of forging and hardening metal that the Sagami School masters invented and used in their works, gained wide popularity during the Nanbokuchō period. Future generations of the school’s smiths, along with many others, attempted to copy and reproduce this technique, one of the most complex sword-smithing methods in existence. Masters from many other areas and schools also tried to apply the techniques of hitatsura in their works. However, the Hasebe School (長谷部) masters, Hasebe Kunishige (長谷部国重) and Hasebe Kuninobu (長谷部国信), replicated this technique most accurately and profoundly. Kunishige, named Hasebe Chōbei (長谷部長兵衛) at birth, was distinguished by his exceptional skill. His best works can safely be put on a par with the works of such recognized hitatsura masters as Hiromitsu and Akihiro. The period of Kunishige’s smithing activity is usually defined as the beginning of the Kenmu era (建武, 1334–1338) until the end of the Enbun era (延文, 1356–1361), which does not correspond to the dates of his life specified in the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen. This book (Volume 2, p. 4/2 and p. 12/2) states that during the Gen’ō era (元応, 1319–1321), Kunishige was in his 50th year; he was born in the 7th year of the Bun’ei era (文永, 1270) and died in the 3rd year of the Jōwa era (貞和, 1347) in his 78th year of life. Kunishige was Shigenobu’s son (重信) and lived in Washū(Yamato) Province. In addition, the Honchō Kaji Kō (Volume “Ox,” p. 23/1) reports that Kunishige was named Chōzaemon (no) Jō (長左衛門尉) or Chōbei (no) Jō (長兵衛尉) at birth.

Generally speaking, in regard to the Hasebe School, its origin and development do not provoke much controversy or many questions. It was founded by Kunishige at the beginning of the Nanbokuchō period. Apart from its founder, the brightest and most skilled representative of the school was Kuninobu (国信). Among its successors and followers, only a small number of smiths can be mentioned—they include Munenobu (宗信), Kunihira (国平), and Shigenobu (重信). At the same time, we should immediately note that despite a large number of extant works by Kunishige and Kuninobu, the works of their successors have reached us only in the single digits. Much more incomprehensible and contradictory are details about the origin of the school’s founder. To begin with, most sources indicate Yamashiro Hasebe Kunishige as the founder, although his style was completely based on Sōshū-Den traditions. Fujishiro Yoshio believes that this name was derived from the fact that Kunishige moved to Kyōto in Yamashiro Province (山城). His resettlement occurred after the fall of the Hōjō clan’s reign in Kamakura. Most likely, Kunishige left Kamakura shortly after Nitta Yoshisada (新田義貞) captured the city in July 1333, and Hōjō Takatoki (北条高時), together with members of his government, committed seppuku. It was in Kyōto where the Hasebe School was created and survived for a very short period of time; it did not last until the end of the Muromachi period.

With regard to Kunishige’s origin, we lack a common, documented point of view. The most accepted version is that Kunishige, along with his brother Kuninobu, came to Kamakura to learn new traditions of the smithing craft, apart from the initial training he had received in his home province of Yamato. After completing his training, Kunishige chose the place of his future residence and work in Kyōto, where he settled near the crossroads of Gojōbomon (五条坊門) and Inokuma (猪熊). The Kotō Meizukushi Taizen states that this resettlement occurred in the Ryakuō era (1338–1340), and the Honchō Kaji Kō, in the volume “Tiger,” refers to the place of his subsequent residence as the crossroads of Gojō (五条) and Inokuma (猪熊). Thus, if we take as truth Kunishige’s origin in Yamato Province, it is entirely possible that he began his education as a smith at either the Senjū'in or the Taima School. The most substantiated version of the story is that he attended the Senjū'in School, because some sources state that his father was Senjū'in Shigenobu (千手院重信). This seems plausible, if we take into account the available data on the period of Shigenobu’s creative activity being Kagen (嘉元, 1303–1306) and the dates of Kunishige’s life (1270–1347). We can see that they do not coincide much, but they are nevertheless within plausible limits. The smith name Shigenobu further appears among the school’s disciples, and it can be considered one point supporting this supposed line of kinship.

The history of the emergence of the family name (mon) “Hasebe” was thoroughly studied and described by Markus Sesko. Perhaps Kunishige’s birthplace was a settlement called Hatsuse (初瀬), located in Sakurai (桜井), which is 20 kilometers south of the city of Nara in Yamato Province. The name of this settlement was later pronounced “Hase.” It is worth mentioning that the word Hase in this region appears in many geographical names. So, for example, a local hill is called Haseyama (初瀬山), and another settlement located nearby is called Hasedera (長谷寺). We should note that in these cases, “Ha Se” is written with different kanji but is read the same way. Therefore, it is impossible to base anything on a difference between the written name Hasebe and the place of his alleged origin, because the pronunciation of these names and locations is identical.

Another very common theory has to do with the kinship of Kunishige and Shintōgo Kunimitsu. According to this viewpoint, Kunishige is Shintōgo’s son, which is supported by the fact that they both used Hasebe as their family name. Moreover, some sources state that at an early stage of his creativity, Kunishige signed his works with his father’s name—Shintōgo Kunimitsu—and used Shintarō (新太郎) as his first name. It should be noted that if Kunishige was among the followers who used the name Shintōgo to sign their work, the years of his smithing activity should be dated from an earlier period. All old sources that support the common line of kinship between Shintōgo Kunimitsu and Hasebe Kunishige indicate the Kareki era (嘉暦, 1326–1329) as the period during which the practice of using the teacher’s/father’s name was common.

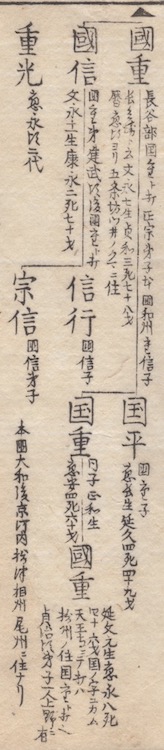

Figure 1. Genealogy of Hasebe School; Kotō Meizukushi Taizen vol.2, p.

This information, as well as the above references to the dates of Kunishige’s life, cannot be explained unless we accept the existence of several generations of the master. Without this, it is impossible to explain the absence of works dated at least to the end of the Kamakura period. We should bear in mind that the master’s earliest work is dated 1346. Also, regarding Kunishige, the fact that he is associated with the name Hasebe does not require any confirmation. In addition to the presence of this name in the school title, most of its extant signed works contain the name Hasebe. It is impossible to say the same about Shintōgo Kunimitsu. It is well known that the variants of his signature—“Shintōgo Hasebe Kunimitsu” (新藤五長谷部部国光) and “Sagami (no) Kuni Kamakura-jū Hasebe Kunimitsu” (相模国鎌倉住長谷部国光)—are preserved only in old meikan. There are neither extant swords nor oshigata with such signatures. The last variant of Shintōgo Kunimitsu’s signature can be found in the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen among other oshigata. But, unfortunately, it is not presented in the form of a nakago oshigata, but simply as a form of the signature without the tang design where it was made.

The history of the emergence of the family name (mon) “Hasebe” was thoroughly studied and described by Markus Sesko. Perhaps Kunishige’s birthplace was a settlement called Hatsuse (初瀬), located in Sakurai (桜井), which is 20 kilometers south of the city of Nara in Yamato Province. The name of this settlement was later pronounced “Hase.” It is worth mentioning that the word Hase in this region appears in many geographical names. So, for example, a local hill is called Haseyama (初瀬山), and another settlement located nearby is called Hasedera (長谷寺). We should note that in these cases, “Ha Se” is written with different kanji but is read the same way. Therefore, it is impossible to base anything on a difference between the written name Hasebe and the place of his alleged origin, because the pronunciation of these names and locations is identical.

Another very common theory has to do with the kinship of Kunishige and Shintōgo Kunimitsu. According to this viewpoint, Kunishige is Shintōgo’s son, which is supported by the fact that they both used Hasebe as their family name. Moreover, some sources state that at an early stage of his creativity, Kunishige signed his works with his father’s name—Shintōgo Kunimitsu—and used Shintarō (新太郎) as his first name. It should be noted that if Kunishige was among the followers who used the name Shintōgo to sign their work, the years of his smithing activity should be dated from an earlier period. All old sources that support the common line of kinship between Shintōgo Kunimitsu and Hasebe Kunishige indicate the Kareki era (嘉暦, 1326–1329) as the period during which the practice of using the teacher’s/father’s name was common.

This information, as well as the above references to the dates of Kunishige’s life, cannot be explained unless we accept the existence of several generations of the master. Without this, it is impossible to explain the absence of works dated at least to the end of the Kamakura period. We should bear in mind that the master’s earliest work is dated 1346. Also, regarding Kunishige, the fact that he is associated with the name Hasebe does not require any confirmation. In addition to the presence of this name in the school title, most of its extant signed works contain the name Hasebe. It is impossible to say the same about Shintōgo Kunimitsu. It is well known that the variants of his signature—“Shintōgo Hasebe Kunimitsu” (新藤五長谷部部国光) and “Sagami (no) Kuni Kamakura-jū Hasebe Kunimitsu” (相模国鎌倉住長谷部国光)—are preserved only in old meikan. There are neither extant swords nor oshigata with such signatures. The last variant of Shintōgo Kunimitsu’s signature can be found in the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen among other oshigata. But, unfortunately, it is not presented in the form of a nakago oshigata, but simply as a form of the signature without the tang design where it was made.

Renouncing this version of the story, we can assume that Kunishige’s connection to the main Kunimitsu line most likely took place through Shintōgo Kunishige—one of Kunimitsu’s sons. The view that Hasebe Kunishige was Shintōgo Kunishige’s son can be found in the narration of Dr. Honma Junji. In this case, we would consider the father to be the first generation of the Hasebe line who did not use this name, and Kunishige as the second generation and the first one who took the name Hasebe and began using it in his signature. The dates of Shintōgo Kunishige’s life in old sources are limited to 1271–1302 and do not coincide with him being Hasebe Kunishige’s father. This is reinforced by the theory that Shintōgo Kuni-shige and Hasebe Kunishige were the same master. Thus, experts who are inclined to place the origin of the master in the Shintōgo line need to precisely identify different generations of smiths, so as not to cause confusion. With a clear distinction, it becomes obvious which generation is considered to refer to Kunishige and how many generations of this school existed, as well as who exactly is considered Shintōgo Kunimitsu’s son.

Despite the fact that the smithing art of Kunishige eventually developed in a separate school, the particular influence of the Sagami tradition in his work is easily traced. One strange fact is that sources pointing out his relationship with Shintōgo Kunimitsu do not list Kunishige among Kunimitsu’s disciples. Almost every source without exception claims that Kunishige was taught directly by Masamune, and his inclusion in the so-called list of “Masamune no Jittetsu” (正宗の十哲) is assumed to be confirmed. This version of history seems the most reasonable, given the dates, as well as the style and quality of Kunishige’s works.

Assessing the master’s work, we can say that Kunishige was one of the most skilled and famous masters of his time. In spite of this, Fujishiro Yoshio assigned him a rating of “only” jōjō-saku (上々作—which is still a very high level of skill). Many of Kunishige’s works, especially the tachi and the katana, exhibit an unrivaled degree of excellence. Most likely, the rating of jōjō-saku was due to the fact that the master‘s long swords survived only in the single digits, plus these were unsigned and undated. Perhaps Fujishiro san decided to evaluate only signed and confirmed short swords, so his rating is mainly based on the large number of extant ko-wakizashi by Kunishige. Comparing actual short and long swords, we note that Kunishige initially maintained higher standards in making long swords. Among his tachi and katana, there are simply no “weak” works. It is likely that the use of hitatsura in long sword manufacturing required the master to use a higher standard of tanren (鍛錬), compared to that used in short sword manufacturing. This led to complications in the process, both in general and in its individual elements. The result of all this was a better final product. If a slightly greater number of long swords had survived the destructive periods of wars, this undoubtedly would have resulted in Fujishiro giving Kunishige a higher ranking. In that case, Kunishige’s position surely would have corresponded to at least a saijō-saku level.

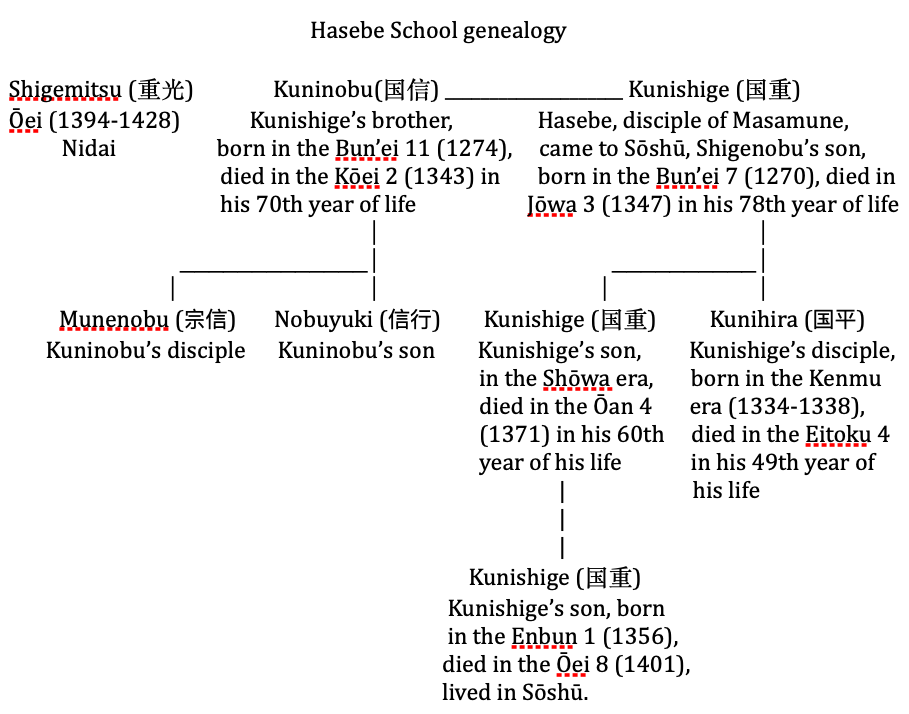

Figure 2. Examples of Hasebe Kunishige’s signature. Kotō Meizukushi Taizen, Volume 7, p. 11/1; Kōzan Oshigata, Volume 乾, p. 57/2, and Volume 乾, p. 57/1.

<.....> With respect to Hasebe Kunishige’s signature, it is necessary to note the features existing in the written “Kuni” kanji. The master wrote it in three different ways:

- Classical (old) style—國;

- 国 kanji with a variation of the middle radical as 王; and

- 国 kanji with a variation of the middle radical, similar to the “Tama” character—玉.

Presumably, the classic (old) style was used by the master quite rarely, judging by the number of swords with this variant of the signature; only three of them have survived to this day. The same trend is observed in relation to oshigata in old sources: we can find only single cases of the old variant of the written “Kuni” kanji. Moreover, such sources as the Kōzan Oshigata and the Kotō Meizukushi Taizen have no similar written variants. The third variation, when the master wrote the “Kuni” kanji in the new style, is sometimes shown by the central stroke being made with a clearly noticeable inclination.

<.....> This approach is somewhat inconvenient, although it was traditionally created so that well-known dated works would comply with these periods. Nevertheless, several sources (e.g., Kotō Meizukushi Taizen, Kokon Meizukushi Taizen, and Honchō Kaji Kō) mention Kunishige and provide quite consistent information about the time spans of the master’s generations. To summarize, we can draw the following conclusion about the corresponding generations of the master:

- The 1st generation: born in the 7th year of the Bun’ei era (1270) and died in the 3rd year of the Jōwa era (1347) in his 78th year;

- The 2nd generation: born in the 1st year of the Shōwa era (1312) and died in the 4th year of the Ōan era (1371) in his 60th year;

- The 3rd generation: born in the 1st year of the Enbun era (1356) and died in the 8th year of the Ōei era (1401) in his 46th year (lived in Settsu Province [摂津]).

Given the peculiarities in the information available nowadays regarding Hasebe Kunishige, it seems reasonable to assume the existence of several generations of masters working under the same name. In this case:

The 1st generation was taught or at least initially was taught by Shintōgo Kunimitsu. There is a theory that perhaps the 1st generation was really only one smith—Shintōgo Kunimitsu’s eldest son, Shintōgo Kunishige, as mentioned above. A representative of the 1st generation worked together with such great masters of the Sagami School as Yukimitsu, Masamune, and Norishige;

The 2nd generation was the eldest son of the first smith and Hasebe Kuninobu’s elder brother. It is possible that the master of the 2nd generation was also taught by the aging Masamune in the last years of his life. Judging by the nature of his work, it is possible that he also worked closely with Sadamune and subsequently collaborated extensively with Hiromitsu and Akihiro. In old sources, the smith of the 2nd generation is described as having the civil name of Chōbei Jirō (長兵衛次郎) and later working in Kyōto near Inokuma crossroad, where, according to the records, the Hasebe School was established;

The 3rd generation is represented by the heir of the 2nd generation, who called himself Rokurōzaemon (六郎左衛門). Sometimes he is called Kuninobu’s son, who later took the name Hasebe Kunishige.

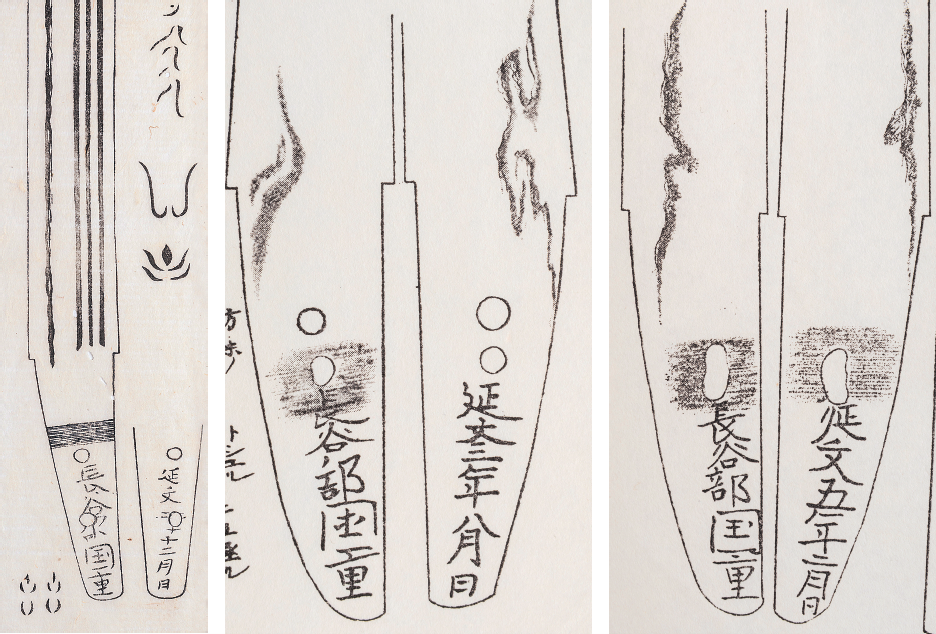

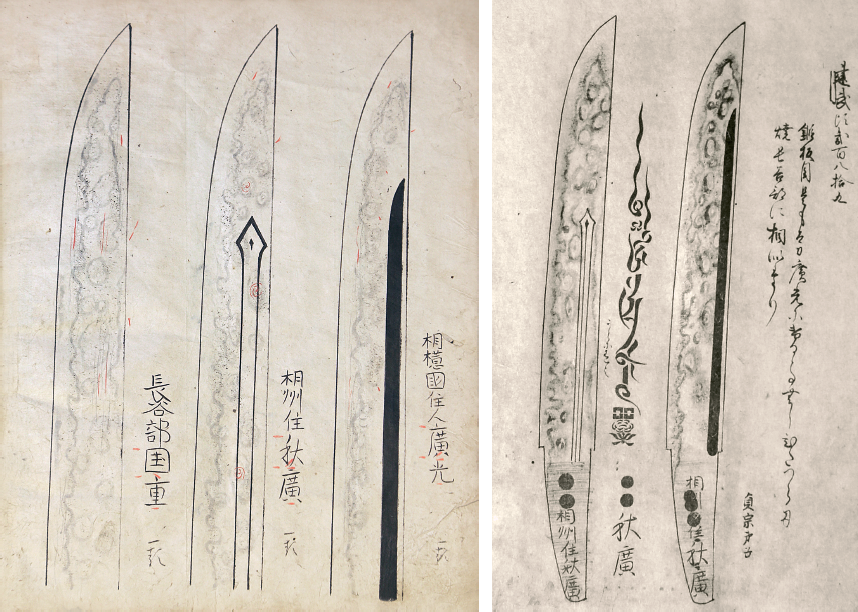

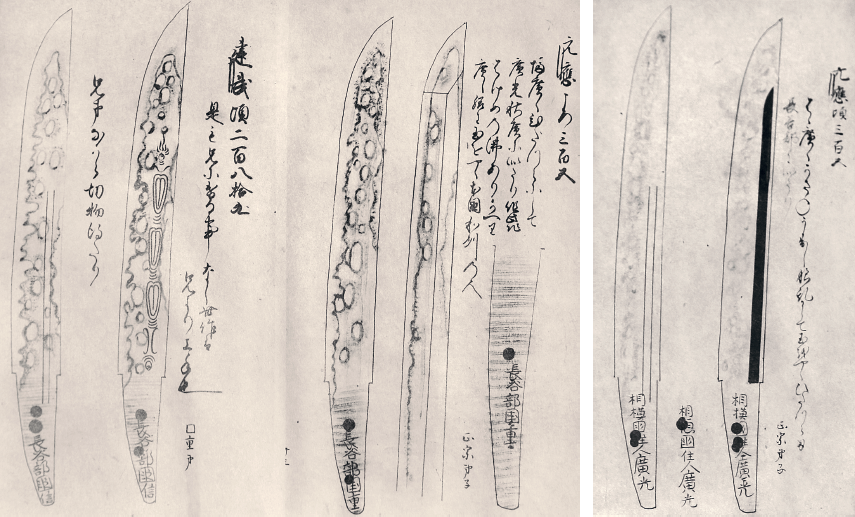

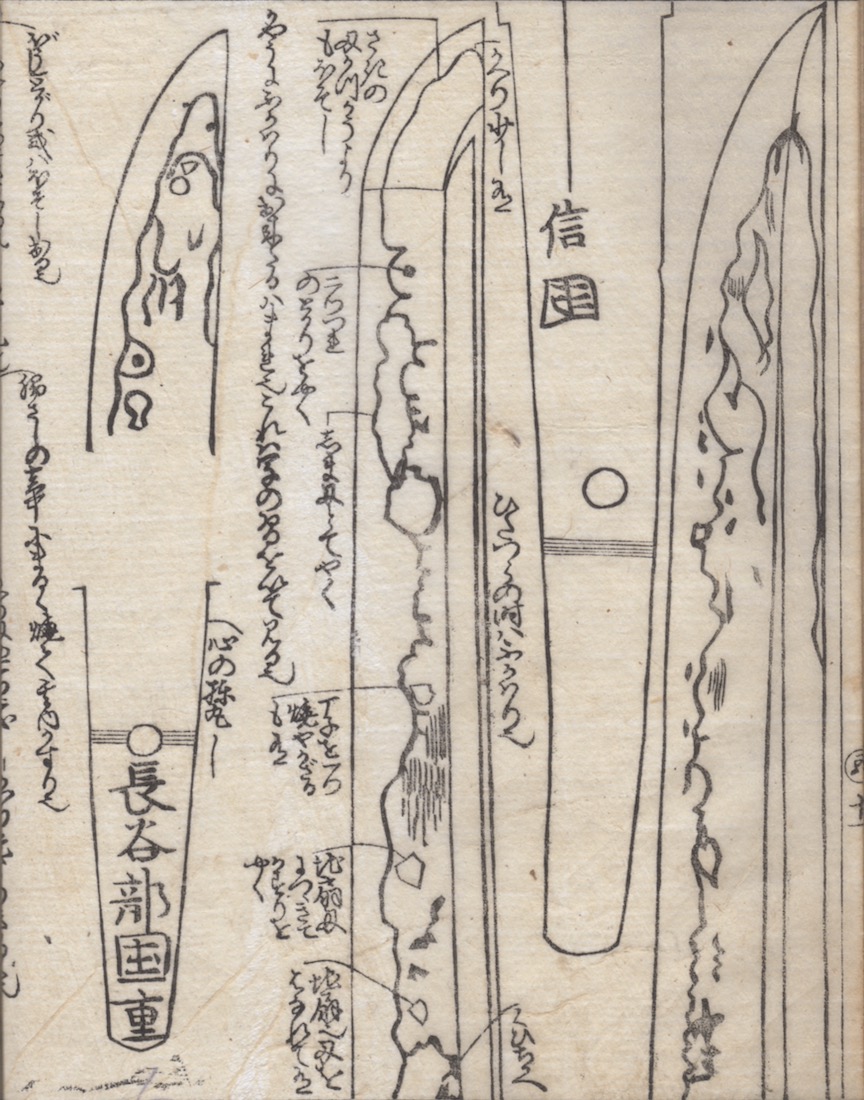

Figure 3. Swords Oshigata. Tsurugi Mekiki Densho, p. 12; Kotō Jōsaku Meikan, pp. 8, 12.

One can clearly see the similarity and the difference in the style of short sword forging by Hasebe Kunishige, Hiromitsu and Akihiro when we study the old oshigata presented in the books Tsurugi Mekiki Densho (剣目利傳書, published at the end of the Muromachi period) and Kotō Jōsaku Meikan (古刀上作銘鑑, by Hasegawa Tadaemon, 長谷川忠右衛門; published in 1941).

Hasebe Kunishige’s works have the following distinguishing features:

Sugata: Basically, these are typical hira-zukuri, ko-wakizashi, and tantō, which are characterized by having a small sori, a wide mihaba, and a subtle kasane with mitsu-mune, iori-mune, and, rarely, maru-mune. Katana and tachi are fewer in number and are characterized as shinogi-zukuri with a wide mihaba and an extended kissaki. Most extant katana and tachi are much shorter than 67 cm.

Jitetsu: A little rough itame-hada of the zanguri (ざんぐり) type, with ji-nie and shirake (白け, whitish areas). In jitetsu, sometimes very dense ko-itame is used; there are tobiyaki and yubashiri.

Hamon: Hitatsura-hamon; we might rarely encounter ō-midareba with a light mix of notare or gunome and, even less often, suguba. The hamon is based on nie; there are sunagashi and kinsuji, sometimes tama-yaki and mune-yaki. Hasebe’s hitatsura-hamon is very similar to those by Hiromitsu and Akihiro, but it has some differences, the most important of which is the pronounced consecutive alternation of small and large areas of soft and hard metal.

Bōshi: Ō-maru with a long kaeri, midare-komi, and nie-kuzure; the main difference in the bōshi hardening technique of the Hasebe School consists of very pronounced roundness of the kaeri.

Horimono: This carving shows great variety. It is possible to find bō-hi, katana-hi, futasuji-hi, soebi, ken, bonji, gomabashi and rendai.

Nakago: The nakago shape in the tantō and the ko-wakizashi is funagata (舟形) with maru-mune and kurijiri. The nakago is short. The yasurime type is kiri. The signature is placed on the nakago close to its end.

Figure 4. Hasebe Kunishige's elements of activity layout. Kokon Meizukushi Taizen, vol. 5, p. 11/2.

(excerpt from Chapter 11, pp. 276-293, of the Japanese Swords: Sōshū-den Masterpieces )

Original content Copyright © 2019 Dmitry Pechalov